Over the years, strikes or lockouts have impacted the officials of every major sport.

L

abor disputes have been a part of American life since shortly after John Hancock put his pen to parchment. Whenever workers have felt mistreated, they have banded together and ceased operations while demanding shorter hours, better conditions, increased pay, retirement plans, more vacation or other benefits.

Labor strife has ended friendships, torn apart families and led to violence. Fisticuffs and firearms are not uncommon on picket lines. As early as 1905, three leaders of the Western Federation of Miners were accused of a plot that led to the death of the former governor of Idaho, a union foe.

Strikes have shut down or slowed virtually every type of industry in the United States, including those dealing with coal, steel, the U.S. mail, air traffic control, railroads, sanitation collection, auto production and law enforcement.

So, it’s no surprise that sports have been rife with lockouts or strikes. And not just the players, but officials and umpires as well. Arbiters in five of the major leagues in North America have sat down or been sat down in disputes with their employers.

Before proceeding, here’s a primer on the important distinction between strikes and lockouts. A strike is initiated by the employees and occurs when the workers cease work. Lockouts are initiated by the employer and are a denial of employment.

As in other industries, sports leagues haven’t been thrilled with the idea of their employees — in this case, officials — unionizing. The mere threat of it ended the careers of two AL umpires.

NL umpires had formed the National League Umpires Association in 1963. Five years later, at a meeting in Chicago, AL umpire Al Salerno was told that if he could get all 20 of his AL compatriots to agree, they could join the union. Salerno recruited crewmate Bill Valentine to contact the five AL crew chiefs about the offer. Within three days AL President Joe Cronin got wind of it and fired Valentine and Salerno, alleging their onfield incompetence. Although sportswriters and major league managers disputed that claim, the pair never worked another game in the majors.

As an aside, the umpires from both leagues — perhaps emboldened by the unfair treatment of Valentine and Salerno — got together anyway and formed the Major League Umpires Association (MLUA).

The history of strikes and lockouts involving referees and umpires is a long one, filled with memorable moments and colorful characters. Let’s review the others in no particular order.

Where’d They Go?

When labor pains involve the officials, the games — even playoff games — go on. The MLB umpires’ first intentional walk kept them off the field for the opening games of both league championship series in 1970. That came in the wake of the Salerno-Valentine case and resulted in the AL and NL recognizing the MLUA as the umpires’ representative in future negotiations.

The umpires have been the most active when it comes to union uprisings. Much of that can be traced to 1978, when the MLUA hired a Philadelphia attorney named Richie Phillips to serve as its general counsel and executive director.

For 21 years, Phillips ran the MLUA with an iron fist aimed squarely at MLB’s jaw. Any slight was met with a sharp rebuke from Phillips. If a manager or player consistently gave umpires trouble, Phillips would announce that individual would receive zero tolerance in future games. He was so persuasive he even got the union members to agree to have his air transit company transport the umpires’ gear from city to city.

He pulled his clients off the field four times (1978, 1979, 1984 and 1991). Two of the strikes lasted one day (one was halted by a court order). Another dragged on for 45 days. The 1984 job action kept umpires off the field for all but one game of the NL Championship Series and every game of the AL series.

In 1995, MLB changed the playoff format from a best-of-five to a best-of-seven. But the umpires’ salaries weren’t adjusted for the additional games. Phillips threatened to have his members work only the number of games called for in the contract. MLB balked. The issue was settled by that paragon of truth and character, Richard M. Nixon, who was approved by both sides as a mediator. Nixon ruled that 40 percent more games was worth 40 percent more pay. The parties agreed and the umpires worked the games.

You can argue Phillips’ methods but you can’t argue with the results. Those walkouts resulted in more pay, more per diem, paid vacation and other benefits that seemed like pipe dreams before Phillips came along.

Phillips overplayed his hand in 1999, orchestrating a mass resignation strategy he hoped would foil Commissioner Bud Selig’s attempts to unify the NL and AL staffs and bring control of the umpires to his office. Instead, Selig accepted 22 of the resignations, the MLUA crumbled and Phillips was fired.

The after-effects of that situation lasted for years. The World Umpires Association (WUA), the successor of the MLUA, inked a new four-year pact with MLB in 2000. The agreement, however, contained no provisions for rehiring any of the 22 fired umpires.

In 2001, arbitrator Alan Symonette ordered baseball to rehire Gary Darling, Bill Hohn, Larry Poncino, Larry Vanover and Joe West, as well as Drew Coble, Greg Kosc, Frank Pulli and Terry Tata. Coble, Kosc, Pulli and Tata were allowed to retire with back pay. Bruce Dreckman, Sam Holbrook and Paul Nauert had given up their right to back pay when they were rehired in August 2002.

In late 2004, the WUA and MLB signed a five-year agreement, and the fate of more of the 22 fired umpires was addressed. Three of the fired umpires — Bob Davidson, Tom Hallion and Ed Hickox — were promised the next openings on the major league staff after going back to the minors.

Six umpires received severance pay and health benefits for themselves and their families. Jim Evans, Dale Ford, Eric Gregg, Ken Kaiser and Larry McCoy got $400,000 each, and Mark Johnson, who had less service time, got $325,000. Kaiser, Gregg and Johnson have since died.

Sub-Standard Subs

Any time referees or umpires have been on strike or locked out, leagues have tried to make do with replacements. Whether they came from the college ranks, were coaxed out of retirement or were promoted from the minor leagues, the results were universally abysmal. Everyone from team management to players to fans to media expressed disenchantment with the substitutes.

Exhibit one came when the NFL locked out members of the NFL Referees Association (NFLRA) for the last week of the preseason and opening week of the 2001 season. It was repeated when the league enforced a lockout that lasted the entire preseason and first three weeks of the 2012 campaign.

The first dispute ended at least partially because of the terrorist attacks on the Twin Towers on Sept. 11, 2001. A different kind of disaster ostensibly brought the second to a close.

A nationally televised Monday night game ended when replacement official Lance Easley ruled a last-second play in the end zone was a game-winning touchdown for Seattle instead of a Green Bay interception. Jaws dropped from coast to coast at the obvious blunder.

Easley used the call, which was dubbed the “Fail Mary,” as a springboard to personal fame. He authored a book, made appearances, was interviewed on local and national television, and was a star on social media (Easley himself uploaded the clip of his guest spot on The NFL Today to YouTube; so much for officials being invisible).

But celebrity has its price. Easley later claimed he suffered post-traumatic stress disorder and severe depression. He told Yahoo Sports he contemplated suicide and had spent time at a psychiatric facility.

Perhaps coincidentally (but perhaps not), the NFLRA and the league came to terms on a new collective bargaining agreement (CBA) soon after the disaster in Seattle. When Gene Steratore and his NFL crew walked onto the field for the first game with the regular officials, the fans in Baltimore gave them a rousing standing ovation.

Replacements were also used by the NBA in 1977, 1983, 1995 and 2009. Twenty-four referees went on strike the last day of the regular season in 1977. Phillips was the lawyer for the striking officials. The strike ended 15 days later after using replacements in some playoff games. The settlement included an increase of $150 a game for referees the rest of the playoffs. Both sides also agreed to collective bargaining after the playoffs.

In September 1983, after the expiration of the previous CBA, the NBA hired replacement officials during the preseason and beginning of the regular season before a three-year CBA was reached in December 1983. In 1995, the NBA announced a lockout of referees because of a “no-strike clause” in the CBA proposal. The league used officials from the Continental Basketball Association and pro-am leagues as replacements. The preseason opened with 41 referees and the league was forced to use two-official crews, instead of the standard three. In December 1995, the National Basketball Referees Association (NBRA) and NBA signed a five-year agreement, and the referees resumed officiating games. NBA officials in 2009 went on strike when the league couldn’t come to terms on a CBA with the NBRA. The league used a roster of 62 replacements in the preseason, plucked mostly from what was then known as the NBA Development League and the WNBA. But in the nick of time, the sides agreed to a two-year contract that provided increases in yearly salary and the playoff pool. After a three-day training camp, the referees returned in time for opening night.

You’d think the Beautiful Game would be immune from such ugliness. You’d be wrong.

The 2004 MLS season began with — you guessed it — replacement referees when the Professional Referee Organization (PRO), which manages officials for the U.S. Soccer Federation and MLS, and the Professional Soccer Referee Association failed to reach an accord on their first CBA. So, PRO executed a lockout that lasted the first two weeks of the season.

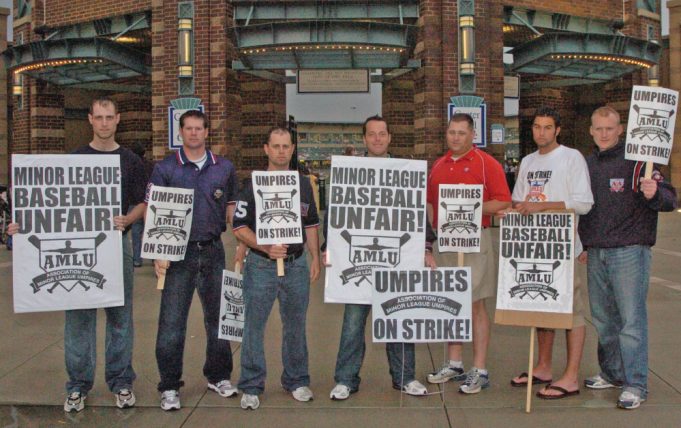

And don’t think this sort of thing only happens in The Show. In 2006, the Association of Minor League Umpires went on strike seeking higher wages and per diems. The umpires skipped spring training and were on picket lines when the season began April 6.

Replacement umpires were used in the interim (of course) and were deemed inept. One manager pulled his team off the field when he didn’t think substitute umpires handled a beanball war correctly. Outfielder Delmon Young was suspended for 50 games for throwing a bat that struck an umpire.

After contentious negotiations that included intervention by a federal mediator, a majority of the umpires ratified a contract that provided a $100 a year raise and a $3 increase in per diem. The umpires went back to work June 12.

Forced to the Sidelines

When the players walk out or are locked out, it may or may not be business as usual for the officials.

MLB players went on strike in 1972 and ’81, sidelining the umpires for portions of those seasons. For those who hold the national pastime near and dear to their hearts, the unthinkable happened in 1994. The entire season — including the World Series — was wiped out by a players’ strike. No games meant no umpires.

The NFL has been the most resourceful in putting a product on the field (albeit not up to usual standards) despite labor woes. When players went on strike in 1987, owners suited up replacement players for three weeks. (One week of games was canceled, resulting in a 15-game season.)

Plenty of good tickets were available for those contests as fans stayed away in droves. Fans in Chicago called their faux warriors the “Spare Bears.” But at least the regular officials worked the games and were paid.

NHL referees and linesmen weren’t that lucky when owners locked out the players and there was no 2004-05 season. The men in stripes were forced to find real-world jobs to support themselves and their families.

They could have worked games for pay at other levels of hockey, but collectively decided they wouldn’t. “It’s not even something we had to debate,” said linesman Scott Driscoll. “(The other officials are) doing it to get to the next level, not for a living.”

“Yes, we all have families to provide for, and we need jobs and an income right away,” referee Don Van Massenhoven said. “But we decided not to do that at someone else’s expense.”

In fact, Van Massenhoven took the policy a step farther. When he approached a car dealer to apply for a sales job, he insisted he would take the position only if he did not take the position away from a “real” salesman.

It was déjà vu eight years later when another NHL lockout occurred. Fortunately, the officials had learned the hard way from the previous lockout. They heard the drumbeats of owner-player unrest and had money set aside to tide them over.

Making a Point

Officials have shown their displeasure with management in ways other than work stoppages.

The most recent example came in August 2017. MLB umpires wore wristbands to protest what they felt was a wrist-slap to a player who had demeaned umpire Angel Hernandez.

According to a statement from the umpires, “The Office of the Commissioner’s lenient treatment to abusive player behavior sends the wrong message to players and managers. It’s ‘open season’ on umpires, and that’s bad for the game.”

The next day, Commissioner Rob Manfred agreed to a meeting with the umpires and the wristbands went away.

In 2004, the NBA suspended second-year referee Michael Henderson for erroneously calling a shot clock violation in a Denver-Los Angeles Lakers game. The officials conferred and decided to rule it an inadvertent whistle and ordered play to resume with a jump ball. L.A. won the tip and hit the game-winning shot with 3.2 seconds left.

After the suspension was announced, all but two referees worked their next game with their shirts turned inside out and Henderson’s number 62 inscribed in marker on the back. The league warned that any official who did so would be subject to discipline. That apparently didn’t happen, but the issue didn’t die.

The five-year CBA that was agreed upon later that year had what was known as the “Michael Henderson Anti-Disruption Clause.” Under a section titled, “No Strike Provision and Other Undertakings,” officials are specifically banned from participating in any strike or “other interference or disruption whatsoever.” According to the CBA, the penalty for such an action is a reduction of the marketing money and/or the playoff pool money by an amount not exceeding $1 million and an additional $50,000 for each official who participates in the action.

Labor Day isn’t just a holiday in September.

What's Your Call? Leave a Comment:

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.