Experienced officials are often asked to mentor men and women who are just beginning a career in officiating. It can be a daunting task to take on. Before you agree to mentor a fellow official, it is a good idea to know what it takes to be a mentor and how good mentors do it.

Mentoring a new or inexperienced official is not just a nice thing to do, it is also a way to better yourself as an official. When you go over the fundamental concepts of things like rules, regulations and techniques, you further ingrain them into your own psyche while you are schooling your student.

“I think becoming a mentor is vital for experienced officials,” said the late Red Cashion, former NFL referee and two-time Super Bowl official. “Teaching others is the best training for both the mentee and the mentor.”

When you go over the more subtle aspects of the craft like appearance, attitude and networking, you not only share knowledge with someone who needs it, but you also remind yourself of things you need to do to be at your best. It is a great way to hone your own game even after decades of work.

“Mentoring helps me stay sharp as a referee; it also helps me open up as an individual,” said Rachelle Jones, an NCAA D-I women’s basketball referee. “I do my best to lead by example and I would never tell an official to do something that I don’t do myself. Whether it is teaching at a clinic, phone conferencing or getting on the floor with you to watch you work, I like to teach the way I like to be taught.”

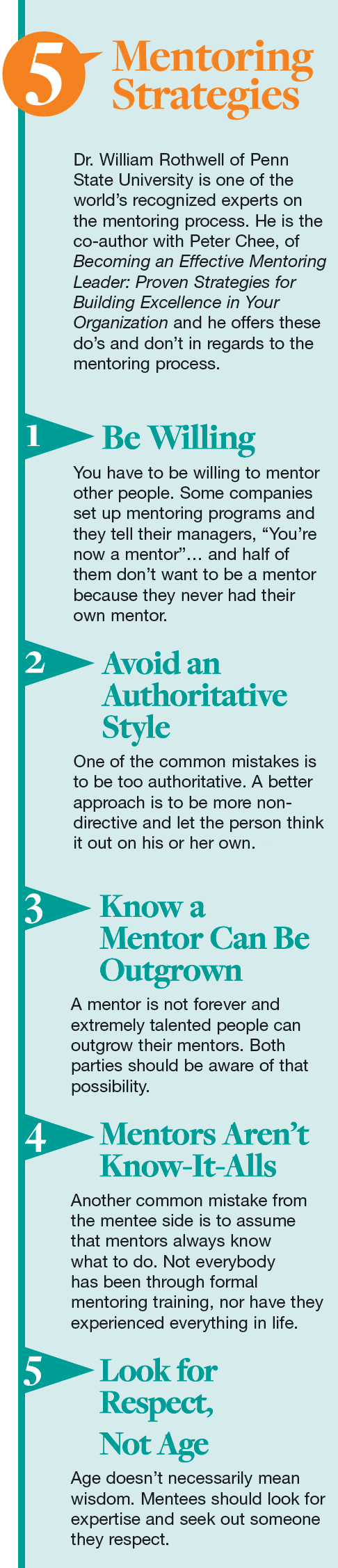

Mentoring others involves its own set of skills and techniques. Here are some tips on what effective mentors do, what they cover and how they go about it.

Teach Patience

Effective mentors not only have patience with their inexperienced students, they also do their best to impart the importance of patience to their mentees. Whether it is patience involving their ability to call the game correctly, or the progression of their career, knowing how to give time is crucial.

“Pretty much the first thing I go over with someone is what it takes to be a really good official and a lot of it is patience and the willingness to learn,” said Jack Miles, a high school baseball and softball umpire in Michigan.

Patience may be a trait that is easier to talk about than it is to practice. Inexperienced officials often don’t have a realistic view of what success will take or even what success will look like for them. Good mentors know how to let them know to be patient and to appreciate where they are — not where they are not.

“I explain to young refs that they have to be willing to be patient and take each day’s experience and use it as growth,” said Angie Lewis, an NCAA D-I women’s referee. “Along the way you have to learn to be successful at the level that you are at the time. It is important to be the best official you can be at any level before you start reaching for the Final Four. Experience is your best teacher and you need patience to make sure that you are excelling at the level you’re at, not always looking for something else.”

Self-disclosure may be your best tool for teaching about patience. In today’s world many young people grew out of the “Everyone-gets-atrophy” mentality and they don’t understand why they aren’t moving along as fast as they could. The answer isn’t to blast them across the room for their sense of entitlement (as much as you might want to), but rather to calmly and patiently share with them a dose of reality on how your career progressed.

“I use myself as an example,” said Mike Koren, an educator and high school basketball referee in Wisconsin. “I have been officiating over 40 years and recently I got my first ever state game. I’ve never had problems filling a schedule and I’ve always been able to work. Working games is not the problem. It took me a lifetime to get to where I wanted to go. When someone says, ‘Look, I’ve been working two years, why aren’t I getting those varsity games?’ I say, ‘Just be patient, it will happen.’”

Dealing With Criticism

With officiating comes criticism. It can’t be avoided but despite the obvious nature of that, many new officials are left distraught over what they hear from supervisors, peers, coaches and fans. A good mentor knows how to coach a student through the criticism and make it a learning opportunity, while minimizing the blow to the mentee’s ego and avoiding damage to an already insecure mindset. It takes a delicate but direct approach.

“You have to look at the positives,” Miles said. “Your mentee could be the worst official in the world, but you can always find things they did well. Try to not dwell on, for example, if a baseball umpire in the second inning doesn’t come up the line, with no runners on, but they did it every other time, you don’t need to evaluate that.

“We sometimes have a tendency to evaluate, or mentor, looking for all the things they do wrong, but I bet you could always find the things they did right. When you’ve pointed out what they did right it makes it easier for them to stomach the criticism you might have.”

It is also important to know when to offer advice and when give an inexperienced official a little break. You don’t have to go over and over every mistake. Too much criticism can be discouraging.

“Be careful of over-advising them and take care not to get them mixed up,” Cashion said. “Too much over advising can get in the way of that.”

That ability to balance the negative with the positive criticism is essential but it is imperative that you let them know where they need to improve. It is something that may not be easy for everyone in the mentoring role — it isn’t always fun letting someone know about their shortcomings. A good mentor knows that pointing out the challenging areas that need improvement is where real growth can be attained.

“I think you have to work with an official and let the official go through a game. When the game is over, do a thorough discussion,” Koren said. “You might want to take a particular play that they could’ve handled differently and say, ‘Is there another way you could have handled that? What was the advantage or disadvantage of the way you handled it? Was that call necessary at that time?’ Talk them through it. What you must do as a mentor is work with the inexperienced officials. Especially at the lower level, let them make a mistake and then talk about it. Talk them through it, analyze the situation, and ask them how would they do it differently.”

The key is not coming out with a laundry list of errors, but rather setting up the process of self-examination through discussion. If officials can figure it out for themselves with a few well-placed, open-ended questions from their mentor, the interaction is so much more powerful than if the mentor takes a dictatorial stance.

Dealing With Younger People

If you have been at your game for decades, mentoring a 20-something official might bring you challenges that have nothing to do with the court or the playing field. The millennials, as they have come to be known, sometimes approach life, work and drive differently than baby boomers. A failure to recognize that can lead to frustration for the mentor and an erroneous assessment of the mentee’s commitment and motivation. Different does not necessarily mean not as good, so when you approach a young person, realize and accept they are from a different time.

“I try to be understanding,” Lewis said. “I try to let them know that it’s not just about being a referee — it’s the whole package. I talk to them about staying the course and considering the commitment they’re going to make to make this part of their life. It isn’t just about being on the court. It is about managing your time, your career and where it all fits in with your family. It is important for them to understand what officiating means off the court.”

Mentoring inevitably involves pointing out where someone could have done something better. That is as much art as it is science, especially with some young people. If you play the hard guy, many will miss the message and leave the interaction with hurt feelings. With a little bit of your own attitude adjustment you can avoid that pratfall.

“I try to make it very clear that I am not criticizing them as a person but instead breaking down the officiating situation so they can learn from it,” Miles said. “I make that very clear and I also let them know how I’ve learned new things 20 or 30 years into my career. I let them know about things I just learned that week or even that day. All of it makes it easier for them to hear.”

It is not about sugar coating everything but rather realizing where a young person may be when it comes to their emotional maturity and their ability to hear what you’re trying to say. Make no mistake, the fundamentals still count and regardless of what generation a group is in, there is no fast track that excuses an official from experience.

“A young official needs repetition,” Cashion said. “They need to get as many reps as they can, whether that is spring games, officiating practice or whatever. It is important to let them know repetition trains them to see things they’ve never seen before. You want them to learn that it is important to start to think about the play before the play happens. You get that through repetition.”

Teach Nuances

One of the harder aspects of mentoring is instructing an inexperienced official on what doesn’t show up in any rulebook or manual. The nuances of the games are tricky and present challenges when teaching exactly how to get a feel for some of the finer points of the game.

“There is stuff that doesn’t fall into the rulebook that referees have to know about,” Miles said. “When I see a referee call a foul 50 feet away from the ball with eight seconds to go in a game where one team is winning by 40, then it is time to have a talk. Then I try to talk them through the process of making good decisions.”

Much of officiating comes down to the desire to be the best you can be and the same holds true for mentoring. The ability to get the nuances of your game across has a lot to do with how much you bring to the role of mentoring in the first place. Just being at it for a long time isn’t enough.

“Someone who’s going to be a mentor ought to be qualified to do it and that means much more than being a competent official,” Cashion said. “You have to want to do it and you have to be able to have more interest in the other person than yourself.”

Take your time and go at the mentee’s speed, not your own. Everyone learns and gains experience at different speed and you need to remember that and apply it. Know that you will need to say things more than once for it to sink in. You also might have to do more than just talk. You might have to show them through your example or video.

“I teach the ‘PIE’ theory,” Lewis said. “I try to get people to understand you have to have people skills, integrity, exposure. … First impressions are lasting impressions so carry yourself accordingly.”

What's Your Call? Leave a Comment:

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.