Today, Jim Reynolds is one of MLB’s most accomplished umpires. His resume includes 16 postseason assignments, including two World Series, plus two All-Star games.

But over the course of his career, Reynolds has been tested, both on and off the field, and confronted an assortment of personal and professional challenges.

James N. Reynolds IV grew up near Hartford, Conn., where he was a three-sport athlete at South Catholic High. His father, Jim III, umpired in local youth baseball leagues and officiated hockey. On a few rare occasions, Reynolds would work the bases for his dad when no one else was available.

“He was one of the guys in town that umpired quite a bit,” Reynolds said. “I think the first game I ever worked, one of the guys didn’t show up, so my dad asked me to work first base. I probably worked two or three Little League games my whole life but I certainly remember my dad going and working games.”

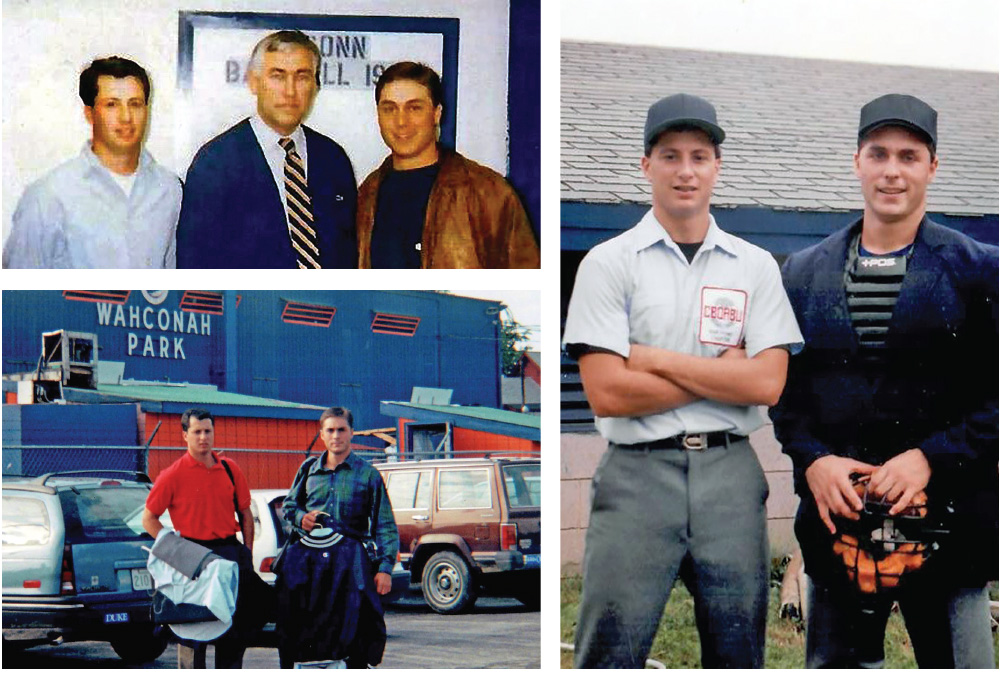

When he enrolled at the University of Connecticut, Reynolds was focused on a career in television news, not calling balls and strikes. But a chance meeting with a high school opponent turned dorm mate changed the course of his life. That dorm mate was Dan Iassogna, who had grown up in Trumbull, Conn., and attended St. Joseph High. He and Reynolds had played football and baseball against each other.

Iassogna’s sights were set on an umpiring career; he had been working games in and around his hometown during the summer months.

One of Iassogna’s friends had played freshman baseball at UConn and told him about a one-credit class on baseball rules that met one night a week and was taught by Andy Baylock, Connecticut’s head baseball coach.

“So, the following semester, I signed up for it,” Iassogna said. “Jimmy and I got to talking and I said, ‘Hey, do you want to umpire?’”

Reynolds was, to say the least, reluctant. “It took Danny two years to convince me to do this,” he recalled, “because I really wasn’t interested. He wore me out.”

Baylock, who spent 40 years in UConn’s baseball program, including 24 as head coach before retiring in 2003, started the class after befriending former MLB umpire Al Forman.

“He gave me a whole bunch of manuals on mechanics and so forth,” Baylock said. “I learned the mechanics, studied the rulebook and started that class. I had maybe eight guys; that included Jimmy and Dan.”

In addition to spending time in the classroom, the novice umpires would call balls and strikes during UConn bullpen sessions. But the real payoff came when Reynolds and Iassogna found themselves umpiring college JV games, which they did during their last two years of college.

The arrangement suited all parties concerned since Baylock’s umpire budget for non-varsity games was zero.

“We would do the JV games and the varsity fall games,” Reynolds said. “When everyone else was on spring break, Danny and I were working four games a weekend. By the end of junior year, we decided to try umpire school.”

Baylock says the two friends’ mutual passion for umpiring was obvious. “They took it very seriously,” he said. “In the summertime they’d be doing youth ball, they were doing a local twilight league in Hartford, they got on the local boards.”

In spring 1991, Reynolds graduated from UConn with a B.A. in communications journalism. He had interned with WFSB-TV, the CBS affiliate in Hartford, during his senior year and the station had expressed interest in hiring him after he graduated.

“That’s what I really thought I was going to do,” Reynolds said. “They seemed very interested in me; I had a great time there and learned a lot.”

In winter 1992, Reynolds and Iassogna — who had earned a degree in English from UConn — enrolled at the Jim Evans Umpire Academy in Florida.

“We had each other which, at least for me, was huge,” Reynolds said. “You’ve got somebody to talk about whatever you’re going through on a daily basis. We were roommates at umpire school. We were college graduates and I think my mentality was, ‘Why not me?’”

Iassogna approached umpire school with the same mindset. “We probably weren’t the best physical specimens,” he said. “We were just two skinny guys. But like umpiring now, the rules are the great equalizer. So, if you could do well in the rules, you could be an integral part of every crew.”

Upon graduation from the Evans Academy, Reynolds and Iassogna were hired by the New York-Penn League and spent the 1983 season as partners.

On one occasion, Baylock made the hour drive to Pittsfield, Mass., to watch the two work. “I drove up and I was so thrilled to see those two guys on the field,” he said. “Then, I went over to the umpires’ room where they were in like a little closet.”

Reynolds and Iassogna were never crewmates after that season, but they stayed in close contact as they traversed separate, but largely parallel, paths to what they hoped would be the major leagues.

“We had each other,” Reynolds said. “We were really, really good friends so whether we were partners, like we were in the New York-Penn League, or when I was in the (California League) and he was in the Carolina League, I could just pick up the phone and I had somebody to talk me through my situations or talk me through my attitude.”

Reynolds gradually climbed the minor-league ladder, spending three years at the Class A level, two in Double-A and two more in Triple-A, but never spending more than a single season in any one league, until 1999 when he started his second season in the International League (IL).

Iassogna was also in the IL at the time and he and Reynolds, along with their peers in Triple-A, were hoping for a call to the major leagues.

“If a contracted staff guy had some time off, you hoped that you were in a good spot,” Iassogna said. “If you were working in Rochester or Buffalo (in the IL), when somebody in Toronto went down with an injury, you hoped that they would call you up.

“There were no cell phones; they would just call your hotel room or call the ballpark. And if they couldn’t get you, they just had to go to the next guy.”

In June of that year, Reynolds got a call from Marty Springstead, supervisor of AL umpires at the time, to start as a fill-in.

A promotion to the big leagues would normally be cause for celebration. But in the summer of 1999, MLB was involved in a labor dispute with the Major League Umpires Association (MLUA).

That July, 57 MLB umpires submitted their resignations en masse, effective Sept. 2. Some of the umpires involved later tried to rescind their resignations; in the end, 22 were accepted and minor league umpires were hired to replace them to start the 2000 season.

When Reynolds got the call, he was in no mood to celebrate. “It was a very, very tough situation for the families of the major league umpires who had spent a ton of time, had 20, 25 years, 30 years in the big leagues and were losing their jobs,” he said.

Reynolds said no one in the MLUA tried to dissuade him from accepting the promotion.

“We (the 22 newly hired umpires) were encouraged by the union to take the jobs,” he said. “There were some people who believed that we (shouldn’t); there were some people who believed that we were scabs.

“To be honest with you, I never envisioned the day I got hired in the big leagues wasn’t going to be a day of celebration. Spending the day on the phone with my mother crying about whether I should take the job or not was not how I envisioned my day going after I got the phone call that I was hired by the American League.

“There were a lot of things going on for a lot of people, but my journey is, I never got a chance to celebrate being hired in my lifelong job. And that’s one of the biggest regrets I have. But again, it wasn’t a time for celebration for anybody.”

Reynolds said there was some resentment at first from some of his new colleagues. “But that was emotional,” he said. “Everybody was going through a tough time.”

To compound the situation further, Reynolds’ parents had gotten divorced while he was working at the Double-A level, and he and his father were estranged. They did not speak for 15 years, but eventually reconciled.

Iassogna, who worked his first MLB game as a Triple-A call-up in August of that year, called the situation “an open wound.”

“There were people whose lives changed. They lost their jobs,” he said. “And some of those people are Jimmy and my closest friends right now. (The union action) happened. I’m glad it’s over.”

Reynolds made his AL debut on the evening of June 4 at Fenway Park in Boston, where he had watched games growing up. He worked third base with a crew that included Larry McCoy, Tim Tschida and the late Chuck Meriwether.

“Marty Springstead was that kind of person,” Reynolds said. “My first game could have been anywhere, but when he had the opportunity to make it in my backyard … he recognized how important that could be to us, to our family, and so my (three) sisters and my mom came out.”

The following season, the umpiring staffs of the two major leagues merged into one. As a newcomer, Reynolds found himself being continually challenged. “It took about five years for them to believe anything I did,” he said. “It took about five years on a pitch right down the middle for somebody not to yell at me. From the day I walked on the field to about my sixth year in the big leagues is all a blur.”

Iassogna, who reached the majors for good in 2004, notes that during that period MLB was adopting a new umpiring philosophy.

“When we came up, we were on the tail end of ‘umpiring is an art form,’” he said. “There’s different interpretations for different umpires. Different guys have different strike zones. Everything was, ‘Can you talk to this guy? Are you approachable, but do you still run your game? Are you willing to stand up to a dugout or stand up to a superstar that’s yelling at you?’ That’s how we were evaluated.

“Now, it’s shifted to so much more of a science. The players will check after the game and they’ll get the information from Pitch Track or whatever and they’ll say, ‘That guy was right. That pitch was a quarter of an inch outside.’”

The learning experience extended off the field.

“You’re learning to navigate the senior guys,” Reynolds said.

“You’re learning how to travel as a big leaguer. You’re learning how to deal with more money than you ever had; we made I think $3,000 a month for six months (in Triple-A) to making $70,000 a year, so there’s a lot to learn.”

Early on, Reynolds learned from his veteran partners.

“I was blessed enough to work with John Hirschbeck and Tim Welke, and Mark Hirschbeck early in my career,” he said. “They (cared about) my development and they provided feedback and I was more than willing to learn and listen.

“I was one that needed all the help I could get and took all the help I could get. You want to be credible with your peers first; that (involves) asking questions about handling situations. What could I have done better?”

Reynolds stressed the importance of a strong work ethic and being willing to acknowledge mistakes.

“It’s about working your ass off,” he said. “You have to be right, you have to be good and you have to learn how to manage people, and you have to learn how to talk to people.

“Certainly I’ve never been somebody that is going to back down from a fight, but I’m also willing to say, ‘Yeah, I screwed that up,’ too. … You don’t use it as a crutch, but when I missed a pitch or when I missed a play I was more than willing to have that conversation the following day with somebody and I think that helps your reputation on the field.”

Reynolds worked the All-Star game in 2004, made his postseason debut the following year, and worked his first LCS in 2010. In 2014, he was assigned his first World Series between Kansas City and San Francisco. He had the plate for game three at AT&T Park (now Oracle Park) in San Francisco.

“I remember putting the ball in play and thinking, ‘Can you believe they put me in charge of this game?’” Reynolds said. “Then, there was the part of me that was the competitor.

“What I liken it to is Sunday at the Masters. This was our major, our biggest major. Does your swing hold up? Can your swing hold up when it really, really, matters?”

Reynolds worked his second World Series in 2018, matching his former dorm mate’s two as Iassogna worked in 2012 and 2017.

In 2020, both were named crew chiefs on the same day, a prelude to perhaps the most unique season in MLB history.

“For the two of us to be named crew chiefs on the same day was an honor,” Reynolds said. “To be recognized by (MLB), but also both of us at the same time.

“The season was the season; it was ballpark, hotel, grind, in that regard. Everything was new. The protocols, the not working with any fans, the ability to hear everything that comes out of the dugout all the time, learning what to ignore and what to address, and really, the unknown of the safety factor too.

“Teams were testing positive, we were having games canceled. Were we going to be affected? The strain that has on your family, not being able to go home like we would normally go home.”

The 2021 campaign marks Reynolds’ 22nd full MLB season. He admits his perspective on umpiring has changed with the passage of time.

“Honestly, every pitch, every play, is work for me,” he said. “I think slowly the last couple years the game has slowed down a little bit.

“I’m not the same umpire I was 15 years ago. My reaction time is the same, but I think with experience comes the ability to slow things down a little bit and be OK with the fact that I’m not the same level of umpire I used to be. I think I bring other attributes to the table now that I didn’t seven or eight years ago. I think experience does that.

“When you’re young, you have the ability to zoom in on whatever your task is, right then and there. And the older you get and the more experience you get and the better that you get, your ability to zoom back out from what your responsibility is, to the whole picture, is what separates umpires I think. I think that’s the thing that allows you to get better and better at this job.”

Reynolds also stressed the importance of maintaining a professional attitude toward the players and managers with whom he works.

“Certainly having familiarity with the people we’re dealing with (is beneficial) and having positive relationships with those people,” he said. “I don’t mean ass-kissing relationships. I mean honest and frank relationships.”

Reynolds is quick to laud his wife, Deanna, for her support. They met in 1998 when Reynolds was working the Arizona Fall League in Phoenix and Deanna was tending bar.

“All the guys would come into this particular bar,” Deanna says, “and the rest is history.”

It was Iassogna who persuaded his friend to ask Deanna for a date. The couple maintained a long-distance relationship until Jim moved to Arizona in 2004. They’ve been married 13 years and have a son, James N. Reynolds V, who is now 11.

“I recognized right away, when we started dating, he had the utmost integrity on whatever he does,” Deanna said. “I saw how he was with his family, his mother and his sisters, how he treated his co-workers, how he treated his friends, and seeing that commitment that he had in all aspects of his life definitely gave me reassurance coming into this relationship. Knowing that there was going to be long periods of time apart, to feel more confident that as long as I’m as committed as he’s committed, we can make it work.”

“My wife and I believe in the institution of marriage,” Reynolds said, “and we’ve worked very hard at it.

“None of it’s easy, especially the stress of this job and the stress of being away from the family, but without Deanna and without James, it wouldn’t be worth it. None of it would be worth it. It’s that simple for me. I get tremendous support from her. I get a lot of support and understanding from my son.”

The 52-year-old Reynolds isn’t sure how much longer he’ll continue to work.

“When this contract is up in four years, I’ll take a serious look at it,” he said. “In four years, my son is going to be 14 or 15 and we’ve missed too much. I’m away from my wife and son too much. I missed him growing up too much and I’d like to help her raise him more.

“I enjoy my job. My job is different every day and I love the challenge of it, but I think I’m going to have more of an impact being at home than I will out on the field.”

What's Your Call? Leave a Comment:

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.