How does the runner usually react when he’s been tackled? The norm in college and pro football is that runners lay patiently after they are tackled and tacklers arise in orderly fashion. That protocol is a learned response.

Players at the high school level don’t always abide by that practice. In effect, they have to learn it, and some of them are reluctant learners. Some high school runners squirm and thrash when they’ve been put on the ground, especially if they’re angry at being dumped for a loss.

A number of problems can be prevented if an official is at the dead-ball site within two or three seconds. Moreover, that official will take charge and use his voice to let the players know he is there. “I’ll take the ball. Use the ground, not a player. One at a time.”

For some reason, it is hard for officials to adopt that practice. Most will be gnawing on their whistles. Only a few will feel compelled to police the pile quickly. That is because coverage in the side zone isn’t as prompt as it could be due to uncertain responsibilities. If the umpire refuses to cross the hashmark and the wing officials decline to move into the field of play, any runner downed in a side zone will rest temporarily without an official covering immediately. Some referees will move to the side zone and retrieve the ball with the wing official poised at a progress spot some distance away, perhaps even remaining on the sideline.

One accepted practice is for the umpire to move into the side zone and get the ball while wing officials hold a spot. The umpire then runs back to place the ball at the hashmark. That practice has the umpire virtually running sideline to sideline while wing officials freeze at progress spots, not picking up the ball.

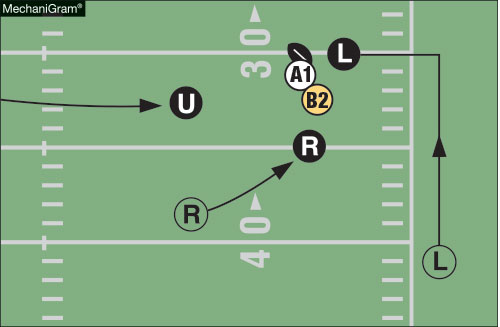

Here’s a system in five-official mechanics that guarantees nearly instant coverage of downed runners in a side zone from the sidelines to the hash.

After squaring off on a play that gains zero to seven yards, the wing official moves onto the field quickly and secures the ball while at the same time obtaining a progress spot. It’s that simple. The object is to provide rapid coverage. But that’s not all. The referee follows the play, swinging outside into the side zone and stays behind the play preparing to receive the relay. He tosses the ball to the umpire for placement at the hash. The umpire also moves toward the dead ball; if it is within several yards of the sideline, he crosses the hash and observes follow-up action at the dead-ball spot. The back judge also moves toward the play. If the gain on the play is more than seven yards, he’ll expect to be the middle person on the relay back to the hash.

That form of coverage has several purposes, one of which is immediate coverage of dead-ball action combined with an accurate progress spot. A second purpose is that four officials are actively closing in on the play, although three of them will stop before getting there. The third purpose is that all four officials will be in a useful proximity to spot post-play behavior by players. A fourth purpose is to decrease the distance between officials for passes that return the ball to the hash. No official should be making a pass of more than several yards.

The prescribed starting position for the wing officials is off the field. That is a sensible procedure, because it isolates the wings away from initial play action. College and pro officials, however, move in and out regularly, collapsing toward the dead-ball spot on every play — even if slightly — and moving swiftly inward to obtain dead-ball progress on first downs and the goalline. The persistent “accordion” movement on the part of wing and downfield officials on every play is not shown on TV, hence high school officials may not pick up on it. Starting from out of bounds does not mean staying off the field entirely.

Moreover, college and pro referees may start from deep behind the eligible receivers in the backfield, but they are also mobile enough to stay on the heels of flushed quarterbacks and to follow play action into the side zone. Although the camera may not show it, pro referees actually spot the ball for the next play a fair percent of the time.

Most high school crews don’t have the luxury of one or two crewmates to help coverage. That’s why a back judge in a crew of five has to be hustling toward the side zone on plays that end near or across the sideline. The back judge should be responsible for coverage out of bounds off the field whenever possible. An oft-heard expression is, “You can’t be killing grass back there.” In college and pro football, when the ball comes dead in a side zone halfway or past the numbers on the field, the deep officials initiate a ball exchange. Therefore, the wing official doesn’t have to get the ball at once. If he does get it, he merely puts it at his feet for a spot.

A variation in the four-person side zone coverage may be required when a sweep moves away from the referee’s established spot on the quarterback’s throwing arm. In such cases — say a three- or four-yard gain — the umpire can move farther into the side zone. The referee can get the second relay pass and place the ball at the hash.

The combined coverage is an effective way to show hustle and coordination for an officiating crew, but more important it is a solid way to cover all action around the runner and to get the ball back in play promptly.

What's Your Call? Leave a Comment:

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.