Check out this portion of a discussion thread from a basketball referee online chat circa 2007:

“Anybody ever notice how a lot of the talk about the stop sign goes something like this? ‘I gave the coach the stop sign and he kept on, so I gave him a ‘T.’”

“My partner gave the coach a stop sign and a minute later the coach went crazy so my partner gave him his first ‘T,’ then I gave him his second ‘T’ a minute later.”

The stop sign didn’t do anything to de-escalate the situation and the value of the non-verbal signal was called into question.

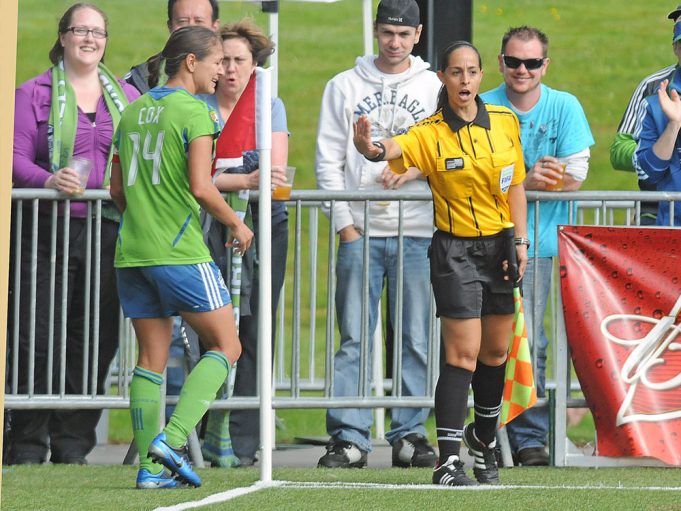

Compare that viewpoint to this recent comment from Esse Baharmast, retired World Cup soccer official and current FIFA trainer of officials for the World Cup: “Absolutely, it (the stop sign) is still a powerful tool. At the international level we have players and teams from all over the world and they don’t speak each other’s language, so we need something like this that says, ‘Please stop. Do not come any further.’

“That way, the message is clearly conveyed.”

In light of those diverging viewpoints, what does the “stop sign” signal mean and convey? Is it an effective de-escalation tool? An over-used dismissive that often hinders communication in games? A socially inappropriate gesture conveying power and superiority that frequently heats up rather than cools down a given situation? All or none of the above?

The answers, it seems, are as myriad as the grains of sand on a beach, and they all depend on, as Missouri State High School Activities Association (MSHSAA) Associate Director Ken Seifert says, “the proper time and place.”

As recently as the past decade, the tool — with the following description: “hand out straight from the chest, kept at eye level or lower” — was still commonplace in many sports on many levels. But some feelings toward it have changed in recent years.

Social mores have changed and the lightning-quick advancement of social media magnifies every close call and perceived slight at light speed. There are certain sports where support for the signal is still rock-solid: international soccer, certain levels of amateur baseball, even amateur basketball, where it is understood that the signal means “enough.”

But elsewhere, that is not necessarily the case. In some realms of sport, it is felt that the sign is overused or even dismissive — its ability to de-escalate has passed.

Players, especially on the professional level, demand to be heard. For many, the stop sign signals the opposite. This has become a major issue in the NBA, where player/official tensions ran high during the 2017-18 season.

NBA administration said the stop sign used to be taught in the league’s officiating training program. “That’s not in their toolkit now,” NBA President of Basketball Operations Byron Spruell recently told ESPN. “We teach them that gestures and words matter. What is in their toolkits is that we want to be humble, and we don’t want to escalate situations.”

Like the NBA, perceptions about the stop sign also affect the way professional tennis sees it, especially with the chair umpire sitting well above the players. The United States Tennis Association (USTA) does not like the signal at all. USTA officials say the optics of it are bad, especially with the social connotations of it looking like a police-style “halt” being issued by the umpires to the players.

“While we have not formally restricted that gesture, we would discourage its use in most circumstances, especially dealing with kids or in a situation where the chair umpire is elevated above a player,” said Andrew Walker, USTA manager, community pathway.

In NCAA volleyball, the signal is not commonplace either, partly because the sport has a similar issue to tennis with the first referee perched high on a stand. However, Joan Powell, coordinator of volleyball officials for the Pac-12 Conference, said the signal “creeps in from time to time.”

“It’s the kind of signal that makes you feel dismissed,” she added. “You’ve crossed a line.”

But Powell added there is a reason for having a second referee at floor level in volleyball. That position is designed to make sure lines of communication remain open and that there is only limited need to use the “stop sign.”

“First, you want to be able to talk to the captain,” Powell said. “Then if something develops, the second referee needs to learn how to corral a coach. Pre-empt any harsh ‘yak-yak.’ That way we can stop things from escalating, stop people from getting (yellow or red) cards.

“We want those people (officials) to say, ‘Talk to me!’ So get in between the coach and the first referee.”

However, on an international level, Powell said variations on the “stop sign” can help keep things calm.

“There was a USA Volleyball junior event and we had a complaint from a parent and a coach where they felt the umpire (first referee) was being dismissive,” Powell said. “They were Puerto Rican and there was a racial tone that they felt had crept in, a language barrier. In situations like that, hand signals seem to help out.

“On the international level a wave of the finger in a certain way can be used to clarify (certain calls).”

Use other tools in conjunction with the stop sign

Baharmast emphasized how important it is for soccer officials to use other tools in conjunction with the “stop sign.”

“The way you use it is as important as your facial expression, the way you look at a player, whether you make eye contact or smile or frown,” he said. “Even the way you use your whistle, whether it’s a short, sharp blast, or a long, drawn-out signal. It’s all part of player management.

“It also matters how a player approaches you, too. If he is walking up to you in a peaceful manner, then there’s no need to use it, but if he’s running at you all agitated then you put your hand out and try to head off a problem.”

Proponents are adamant that if used properly, it is still effective in keeping emotions in check at games. Seifert, who is also director of officials for the MSHSAA, is solidly behind it.

“When it comes to that (the stop sign) I’ve seen both sides of the hand,” he said, referring to the 14 years he spent as a junior college basketball coach as well as his current 14-year run as a small-college basketball official, “and with that said, I do understand that officiating is a human relations business.

“Though we have no formal policy toward it (in Missouri), we encourage everyone, at any time, to use non-verbal forms of communication as a positive way of getting their message through. As a coach, in common terms I understood that when I saw that signal, I knew that that particular individual had had enough of me. Their cup was full (at that moment).

“But I also knew that I could bring up another issue (with him or her) at a later time. That signal I felt never hindered my ability to communicate a different issue.

“When I was an official, looking at the back of my hand, I always thought its effectiveness depended upon the situation, because every situation is unique. I found it effective only in the right time and place. You overutilize it, it will lose its effectiveness. It can be seen as an abuse of authority.

“I know they’re having problems in the NBA (with it), but be careful of what you wish for, because if it is discouraged, I’m not sure there’s another form (of warning) that we have. We would have to go straight to the penalty phase and the players would like that even less.”

In the past, Referee has been a cautious proponent of the signal. In a 2009 column, it was noted the “stop sign” could be used in a multitude of situations: defusing a coach in a confrontational situation; telling a coach or player in a non-confrontational situation, “I’ve heard you, I got your point, but let’s move on”; calming down a player who has been fouled flagrantly. One writer stated: “If you use it sparingly, the offender and others will know that a warning has been given. Then if the offender acts up again (and) is whistled for a technical foul, you have visual proof (possibly on videotape) that the offender was previously warned.”

Both Utah High School Activities Association (UHSAA) Assistant Director Jeff Cluff and NCAA National Coordinator of Men’s Basketball Officiating J.D. Collins provided support for that contention.

Cluff, who is director of baseball and all officiating for the UHSAA and who has been a high school, junior college and NCAA Division I baseball umpire for more than a decade, said his state’s association has no formal policy on the stop sign. From his personal standpoint, he said if an umpire is communicating well with the teams he or she is working with, he or she shouldn’t have a need to use it.

In certain situations, the stop sign holds more value

“I really don’t necessarily use it a whole lot,” he said, “but there are certain situations where it is of value. I still believe it works. Along with the correct language it still does what you want it to do as an umpire. Coaches will usually understand.”

Cluff described a scenario of a coach chirping about balls and strikes.

“On the first level (warning) I would use the mask, take it off and give a look,” Cluff said. “And on the second level I would use a loose definition of it (the stop sign) and that should let the coach know that I am done with this particular issue. I have drawn a line in the sand.

“It would be like saying, ‘If you continue like this you will leave me no choice but to eject you.’”

Cluff said the stop sign is not used much at all in higher-level collegiate games. “Most coaches respect what we’re doing,” Cluff said. “It’s only in the cases of misapplication and missed calls that things get heated. You use a mix of verbal and non-verbal signals to get your point across. But I have used it a lot more on the high school and JUCO level. Overall, as far as I’m concerned, I don’t think it’s in decline and I think we’re careful not to overuse it.”

Collins said as far as NCAA men’s basketball is concerned, there is no policy for its use or nonuse. Like others, he just advises people not to wear it out.

“I tell our officials to use all their communication skills first,” Collins said. “Of course, be a good listener, but if a coach comes at you, give a clear and decisive stop sign. It should tell the coach that he or she can only come so far and if the official is pushed, and the coach keeps coming at you, then it is a technical foul.”

As noted, the less it is seen, the more effective it will be.

“If you’re in the habit of using it a lot, using it almost every time, then there’s a problem. Then you haven’t done enough to communicate (with that coach),” Collins said. “Use it (only) if they’re berating you or if they’re harping on the same subject over and over again because it is taking your attention away from what should be your primary focus, which is calling an effective and fair game.”

Collins said he learned the signal from the late officiating legend Jim “Boomer” Bain.

“He told me to give them a clear and decisive stop sign,” Collins said. “‘Make it clear enough that a person in the top row of the stands can see it,’ he said to me.

“And we do continue to use it as a teaching point, something we go over every year. We find that some do it well and others need a little help. We want them to use it in a clear and concise way. Don’t make it a casual turn of your back or wave of the hand.”

Ultimately, officials need to apply to the stop sign the same thing that’s applied to the use of other communication tools: good judgment. It may be appropriate for some situations or only inflame matters.

“There are different ways of doing things,” noted Baharmast. “We work with players from a wide variety of cultures — Asia, Africa, South America, North America and Europe — and to manage all those players, we have to use all the tools at our disposal.”

What's Your Call? Leave a Comment:

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.