Don’t take a knee. No, I’m not referencing protests during the national anthem. I mean don’t take a knee when calling pitches or plays. I recently saw a game where there was a steal play at second base and the umpire did this. It reminded me of how much my thinking about this changed over the years.

Working on a knee was quite the rage in the ’60s and ’70s. Several big-league umpires did it when calling pitches as well as plays at the plate and on the bases. We learned in Umpiring 101 that our body — and especially our head — must be steady as pitches arrive, because once we form our mental “window” through which pitches must pass to be strikes, it will move around if we’re moving and this destroys our consistency. The “knee” umpires seemed so steady and relaxed that I quit working a box stance and copied it, believing this would make me as stationary as I possibly could be as the pitcher delivered.

And it did. Eventually, however, it became clear to me that there are more downsides than upsides to working this way. So I switched back.

For one thing, catchers didn’t crowd the plate then like they do now. They gave you an open slot in which to set up so you could track the pitch into the mitt, which is another essential part of calling pitches correctly. If they worked too far inside, you could ask them to move over and they’d oblige. But as time went by, they began working inside more consistently and if I asked them to move, they’d tell me that this is what they had been told to do.

Even as tall as I am (6 feet, 4 inches) I couldn’t see pitches into the mitt with catchers right in front of me. In particular, I lost sight of pitches down in the zone. When you’re having trouble seeing the low pitch, don’t get lower; on the contrary, you need to get higher, and I couldn’t do that on a knee. By the way, if the catcher crowds the inside, never work over his opposite shoulder. If the hitter is jammed and you have to rule on whether the ball hit him, his bat or nothing, you won’t have a clue. Work over the top of the catcher’s head like AL umpires did when they wore the outside protector back in the day.

That I found myself increasingly getting blocked out was the main reason I got off my knee, but there were others. One problem is that it looks lazy, especially if you stay down for more than one pitch at a time, as I did when the game dragged on and I got tired. (My record is eight pitches without getting up, including throwing a new ball to the pitcher after foul balls.) Indeed, perception is one of the main reasons why some umpire systems banned this stance.

If you’re on a knee, you’ll have to shift if the catcher shifts before the pitcher begins his delivery, and this can be awkward. And if the catcher shifts from the middle to the inside part of the plate, as they often do, you may get blocked out at the crucial, very last second. The only way to avoid having to shift is to wait as long as possible to set up, but even then you may end up staring at the catcher’s back.

Waiting until the last instant to take your stance may also cause you to be moving when the pitcher delivers, and that’s not conducive to solid pitch-calling. Finally, if there’s a pitch in the dirt and the catcher has to shift his body and feet to block it, or a pop foul or wild pitch that he has to chase, being on a knee may cause you to interfere with him. This happened to me a couple of times before I went back to the box. Same thing if you’re on a knee with a left-handed batter and the catcher makes a snap throw to first to try to pick off a runner.

You need a locking mechanism to keep you steady as the pitch arrives

So even if you’re allowed to work on a knee behind the plate, my advice is don’t. You need a locking mechanism to keep you steady as the pitch arrives, but there are a variety of other options. Watch major league umpires on TV and you’ll see them. Do not put your hand on the catcher’s back, as some of them do; it’s not appropriate in the amateur ranks.

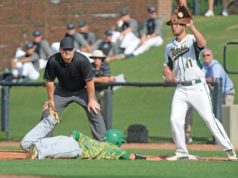

As for calling plays, going to a knee does keep you steady, which is why I also did that for a time. However, you can’t adjust if the play develops unexpectedly — say a throw to the first baseman is off-line, he has to shift to catch it, and the only way to see if he keeps his foot on the bag is to adjust your body. It’s hard to do this on a knee. If there’s an overthrow and you have to take the runner into second, as in a two-umpire crew, you’ll lose the time it takes to get up and start running, especially as your age creeps up and getting up isn’t as easy as it used to be.

On tag plays, runners sometimes slide in ways we don’t expect, and fielders must chase them with their glove to tag them. If you’re on a knee and the play goes away from you, it’s hard to adjust to be in position to follow it to its conclusion. The fielder could miss the tag by a foot and you won’t be able to tell. It’s especially difficult to see if a runner overslides the bag and you have to rule on whether he got his hand or foot back on it before being tagged.

In sum, if you work on a knee behind the plate or on the bases, get away from it and stay upright. You need a steadying mechanism that lets you stay locked in as the pitch arrives or the play develops, but there are simply too many problems with the knee as that mechanism.

What's Your Call? Leave a Comment:

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.