Unlike in football and basketball where referees must determine the legality of athletes crashing into each other on almost every play, baseball is a more tranquil sport. Except when it comes to the double play at second base.

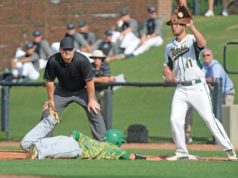

The double play is surely the exception to the rule in baseball and easily rates as its most physical play. Once a month, umpires might need to decipher a collision at home plate, but the double play can happen three to five times in a seven-inning game. Baseball umpires know the play all too well — the shortstop or second baseman receives the toss, touches second base and throws to first base as the runner from first base is sliding in to second base at high speed trying to break up the play.

The physical contact at second base can trigger a wide variety of issues. Fielders get angry when they get hit. Runners get overly aggressive with their legs and arms. Players are injured. Defensive teams, especially on the lower age levels, vigorously celebrate the “twin killing,” which can lead to unpleasant exchanges between teams.

To exacerbate the situation, this play can be a major blind spot for umpires working in a two-umpire crew. Once the fielder transfers the ball to throw it, the base umpire will turn his attention to first base. According to two-umpire mechanics, the home plate umpire positioned more than 100 feet away then assumes responsibility for the interference call — an imperfect situation.

So it is imperative for umpires to learn the interference rule on double plays, how to interpret it and how to call it on the field. All levels of baseball have strict rules to address this specific play referred to as a force-play slide.

“This play is always a hot button because as soon as you call it, you are calling two outs,” said Mike Lum, a 20-year umpire who has worked NCAA games for the last five years. “It takes guts to make this call because you know that you will need to explain it to a coach.”

The force-play slide rule is widely misunderstood at all levels. In all rule sets (NFHS, NCAA, pro), there is no requirement for players to slide. If a player slides, however, it must be a legal slide. On the double play at second base, the runner must either peel off away from the base to not interfere with the throw or slide legally. Another important point: Interference on this play is not contingent on if the batter-runner would have been out or safe at first base.

So what is the force-play legal slide rule?

Rule 8-4-2b in the NFHS rulebook states any runner is out when he “does not legally slide and causes illegal contact and/or illegally alters the actions of a fielder in the immediate act of making a play, or on a force play, does not slide in a direct line between the bases.”

The definition of an illegal slide, according to rule 2-32-2 in the NFHS rulebook, lists a few important distinctions:

- The runner uses a rolling, cross-body or pop-up slide into the fielder.

- The runner’s raised leg is higher than the fielder’s knee when the fielder is in a standing position.

- Except at home plate, the runner goes beyond the base and then makes contact with or alters the play of the fielder.

- The runner slashes or kicks the fielder with either leg.

- The runner, on a force play, does not slide on the ground and in a direct line between the two bases.

The NCAA rule provides less protection for the fielder but is largely similar to the NFHS rule.

Under NFHS and NCAA rules, if interference is committed by a runner with the effect of preventing a double play, regardless of his intent, the batter-runner will be called out in addition to the runner who committed the interference. All other runners return to their bases at the time of the pitch.

Offensive interference calls often lead to protests from the offensive team, so it puts a premium on umpires calling the play definitively and explaining it well to coaches. Lum suggests the following sequence:

See the violation.

Emphatically signal and call, “Time.”

Point to the play and announce, “That’s interference.”

Point to the runner who committed the interference and pronounce, “You are out.”

Point to the batter-runner at first base and announce, “You are out.”

“The more you sell this call, the more it helps you,” said Lum. “Your verbiage with the coach needs to include something from the rulebook. I like to say, ‘The slide was not in a direct line to the base,’ and that usually satisfies the coach. When you can recite the rule, the argument is usually short and sweet.”

Tim Gaiser, a 23-year umpire who has worked 18 years of college baseball in upstate New York, says the force-play slide rule is one of the few plays in baseball where you have evidence to support your call.

“This play involves a player sliding into second base so there will always be slide marks in the dirt,” said Gaiser. “If the player slid on the north or south side of second base, there will be evidence to prove it. I show the slide marks to coaches when they come out to protest the call. Interestingly, I know many quality umpires who even out the dirt — like cleaning a blackboard — around second base between innings so they have a fresh area there for the next play.”

The focus on the double play has intensified recently in college baseball. This play attracted national attention in Game 2 of the championship series of this year’s College World Series between Florida and LSU. In the seventh inning, LSU had the tying run rescinded when one of its players was called out for interference in attempting to break up a double play. Additionally, the Southeastern Conference will expand video reviews of umpire calls in 2018 to include breaking up the double play at second base.

Only recently has MLB followed suit with lower levels of play to restrict the actions of offensive players trying to break up double plays. (See pro 6.01j for details.) The new rule, commonly referred to as the “Utley Rule,” took effect four months after the Los Angeles Dodgers’ Chase Utley rolled into an airborne Ruben Tejada during the 2015 playoffs against the New York Mets. Tejada broke his leg on the play.

“This is a safety rule that needs to be enforced,” said Gaiser. “It needs to be called, and called consistently.”

What's Your Call? Leave a Comment:

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.