While extra education at camp is invaluable for umpires who are dedicated to working on their craft and/or looking to advance to a higher level in their career, it doesn’t come without the occasional obstacle. One of the biggest is deciphering what you should do when you are given conflicting information about the proper umpiring mechanics of a given play.

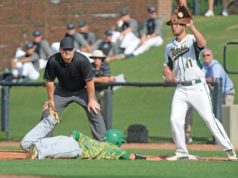

Case in point: When working the A position, where should you move to take plays at first base following a ground ball that’s hit somewhere in the infield?

Go to one camp, and you’ll receive detailed instruction about working hard to obtain a 90-degree angle with the location from where the throw originates. So, if a ball is hit to the third baseman, you are going to take at least two to three additional steps into the infield dirt toward second base than if the throw is coming from the second baseman who is deep into the hole moving toward shallow right field.

Fast forward a couple weeks, and you may find yourself at another camp where you’re taught the 90-degree rule is out of style, and instead all you need to do is to take one or two steps off the foul line for all plays at first base, because this gives you the best angle to see if there is any daylight between the first baseman’s foot and the bag when he catches the throw.

Sound familiar?

Every good camper knows which mechanic is correct: It’s the one being taught in that moment. You do as the instructor wants you to. Six months later, when you’re lined up for the first pitch of the new season and anticipating that first ball being put in play, your pre-pitch preparation, your read of the action and muscle memory are going to dictate which mechanic you use.

And here’s the good news: Neither is wrong … until it is. Because as we all know, no two plays are created or executed exactly the same. The mechanic that might best fit one particular play may not be best suited for another. That’s where we need to use all of the tools in our bag to get in the best position to make a ruling.

For example, let’s say you’re a general practitioner of the second mechanic — you take one to two steps off the line each time and achieve a strong position for ruling on a possible pulled foot whenever possible. With that in mind, the leadoff hitter drops a bunt that rolls 10 feet into fair territory, the catcher pounces on it and here comes the throw on a bang-bang play at first base.

The good news is you may have a great look at whether the first baseman pulls his foot. The bad news? That first baseman is stretching toward home plate, not one of his fellow infielders, in anticipation of the throw. And given your positioning near the foul line, you are looking through his back, trying to determine when the baseball has entered his glove without a clear line of sight for doing so.

Now, imagine the look you would have at the play by taking two or three more steps toward the middle of the diamond. Not only do you still have a great view of whether the foot remains on the bag — I would argue it’s an even better view because it involves the very front corner of the base with any possible foot pull going toward the plate — but also a clear view of the thrown ball as it approaches the glove. With this small positional adjustment, you have created an optimal look at all the necessary pieces of information needed to make — and sell — this ruling.

Conversely, let’s say you ride or die with the 90-degree angle. A ball is hit deep in the 5/6 hole, the shortstop fields it and his throw is up the line to the right-field side of the bag. The first baseman stretches almost directly toward you and you have a great look at when the ball enters his glove.

The problem? You have no idea if he kept his foot on the base, as you are in no position to see if there is any separation due to the first baseman’s movement coming at you instead of away from you at any type of angle. Rest assured, this is going to be a play where a coach is going to ask you to go to your home-plate partner for help, and you’re going to realize you need it, as you’re not sure if he held the bag or not.

Reading the ball off the bat and realizing this is going to be a close play where a pulled foot is a strong possibility, this is a good opportunity to stay near the line and make sure you have a great look at that particular element of it. Because the ball is coming from an infielder, you’ll still have an unobstructed look at the catch/no catch by the first baseman. Staying near the line gives you the best opportunity to have all the information you need to make this ruling.

As these two examples show, umpires need to be able to read plays and adjust, and understand when the dictums about “always” taking a play a certain way do not apply. Yes, there are absolutes we must follow when ruling on force plays at first base. We don’t want to be moving, so that our eyes have a set look at the action. We want to be far enough away from the play to see everything and not allow it to blow up on us. We want to do everything we can to remain in fair territory, as taking a force play at first base in foul territory in two- or three-person mechanics has the potential of creating additional problems for you and the crew. We want our timing to be on point, so we aren’t in the middle of our big “whacker” mechanic with the ball lying in the dirt.

Where do we set up shop to make that ruling? That comes with feel, experience and understanding it’s not necessarily a final destination, but a road map to help you ultimately get where you want to be.

What's Your Call? Leave a Comment:

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.