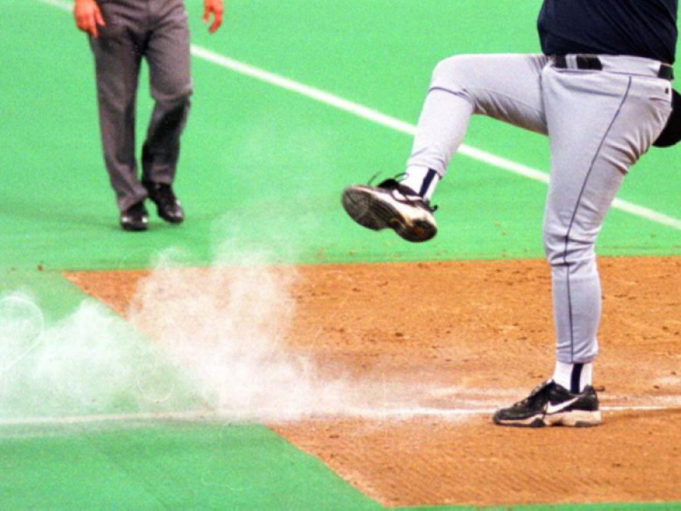

Warnings — Give ‘em “the look,” “the stop sign,” the quiet word, the louder word, it doesn’t matter if you never take care of business. Warnings are not enforcement. Technical fouls, red cards and ejections are.

It’s a common scene in games these days: The official clearly warning a nearby coach or player that that’s enough. Maybe he’s putting up the “stop sign” with his hands. Maybe you can see him having a quiet word with the coach or player. But how effective are those warnings if there’s never any follow through?

One of Peter Sellers’ last movies was the dark comedy, Being There. In that cult favorite, he played Chance the gardener, a dapper, millionaire’s gardener with the mind of a young child. As the plot developed, Sellers’ character rose inadvertently through society’s ranks by affably doing nothing and blithely repeating the same few innocuous phrases.

People, desperate for a hero, mistook his shtick for wisdom and character so that, by the time the credits rolled, he was being touted as a presidential candidate — to the horror of the audience. The movie satirized our culture’s tendency to equate success more with doing nothing wrong than with standing out and making a difference.

Michael Josephson says officials are doing a huge injustice when they choose to play “Chance the Referee.”

Josephson is the founder of the Josephson Institute of Ethics, which has carried the Character Counts! program to more than five million schoolchildren in the U.S. The former law professor and former NASO board member is an outspoken proponent of officials applying the rules as written for the betterment of the game.

“It isn’t why refs warn too much but when they warn that is the issue,” says Josephson. He believes that officials cause problems for themselves when they change the standard of what they’re calling in response to the game situation. He sees some warnings, used when dealing with infractions of questionable importance, as a valid use of common sense. But he objects strongly when warnings are used as a substitute for “pushing the button.”

“When somebody becomes more discretionary because he or she is concerned about the effect of making the big call, then that official is intimidated,” he contends. “It amounts to having been bribed.”

Josephson acknowledges that fans, players and coaches demand consistency from officials

more than any other single attribute. He thinks that if the refs wouldn’t worry about the effect of their calls but simply make them per the rules, they would automatically create a high level of consistency. That, he feels, would make their jobs easier than spraying around warnings and creating the impression of inconsistency, indecision and even bias.

Rick Hartzell is a veteran of more than 1,600 NCAA Division I men’s basketball games and a proponent of that same head-on approach. He wonders what our lives would be like if we handled our families the same way he sees some refs handling players.

“Suppose you’re sitting having dinner and your son decides that it’s a great idea to start throwing peas at his sister,” he begins. “As he raises his arm, you say, ‘Don’t throw that pea at your sister,’ and then he does anyway. Then, as he reloads, you warn him again and he does it again. After about the third time, he concludes that you aren’t really serious. Then he wonders what else he can get away with.”

The solution, says Hartzell, is not to worry about being friends with your children any more than being friends with the players when trouble’s brewing. “What you’d do with your son,” Hartzell goes on, “is tell him the first time he takes aim, ‘If you throw the pea, you’re going to your room.’ Then, if he does, it’s whack, ‘Go to your room.’ There’s no middle ground. I told you what would happen and you did it anyway. Goodbye.’

“He’s had his chance. Then, when he’s sitting in his room wishing he could be back at the table eating and doing all that other fun stuff, he gets the idea not to try that again. And probably nobody else at the table will try either because they’ve seen what will happen. It makes for better family time.”

And carried further, for better game time, too. Hartzell’s analogy supports Josephson’s belief that simply following through on warnings is the best approach. But if you’re giving warnings and then meting out justice all the time, aren’t you being authoritarian? The two agree that it depends on the sort of things you choose to warn about. They agree that there can be no warning — only justice — on some issues, like sportsmanship.

Somehow, many officials think it’s better for their future if they avoid “iffy” penalties and

sanctions by covering their tracks with warnings. It sounds awful, but the reality is that’s sometimes true.

Forget, for a moment, about officials just trying to get through the present game and endearing themselves to the right people to get another game next year. How difficult does one official’s leniency make it for other officials sent in next? The answer is a resounding “very difficult” from all parties.

Hartzell puts it best when he points out that one of the key victims of one referee’s excessive leniency is Hartzell himself. “The only way you earn credibility in this business,” he explains, “is to go back and go back and go back. You don’t do much for your own credibility when you don’t take care of business every time you’re there.”

With enough exposure, teams and players become familiar with an official’s tendency to wilt at the moment of truth and they try to manipulate him. He also hurts his fellow officials when coaches see “the line” being drawn in a different place by the next crew: If coaches suffer enough losses or see an erratic foul count from game to game, it sets them off on a mission looking for the exceptions to the consistency they expect. And it’s the soft — or excessively inflexible — official who takes the heat.

What makes officiating so much fun is that somebody will be disappointed by whatever

choice is made. If they’re really disappointed, people boo, players moan, coaches rant and administrators phone. Could it be, then, that the overuse of warnings is an attempt by some officials to do the job but spare themselves the agony?

What's Your Call? Leave a Comment:

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.