NBA fans’ character sketch of Joe Crawford has been drawn in indelible ink. They long ago dismissed him as that referee with a centimeter fuse who occasionally highjacked games with his raging inferno of a temper.

The signature case in point is unquestionably that Sunday afternoon in Dallas in 2007 when Crawford damn near imploded. That’s the time he ejected San Antonio Spurs all-star center Tim Duncan for laughing at Crawford from the bench. Duncan even claimed Crawford challenged him to a fight as emotions overflowed in the American Airlines Center. It’s all there on YouTube to see for yourself.

That was the end of Crawford’s season, if not career, after then-NBA Commissioner David Stern handed down a statement that opened with the ominous words, “Especially in light of similar prior acts by this official, a significant suspension is warranted.”

So how is Crawford still at it more than seven years after that meltdown for the ages? And why in the world has he been named the recipient of the prestigious Gold Whistle Award, which places a significant value on contributions to the betterment of officiating, by the National Association of Sports Officials (NASO)?

The answer to the first question is that he has been one of the elite officials in the NBA since 1977 and he overcame his personal demons in the wake of the Duncan incident, when Stern’s suspension evolved into a career-altering epiphany for Crawford. Among his most passionate desires is to be remembered as an official with whom peers wanted to go to war and that has certainly been the case for years.

“One of the main reasons you wanted to work with Joe was you knew the game was going to be taken care of from a game-management point of view,” said retired official Steve Javie, an ESPN rules analyst who is one of Crawford’s closest friends. “Also, I knew I could learn each night from Joe. He is the best teacher and he knows how to protect his crew on the court if trouble happens.

“I know when I was a young official, I made a lot of mistakes and he would not be afraid to let me know about them. But he always had a way of telling you why you made them and trying it with a different approach just might be better.”

Quite simply, the officials who embrace the chance to work games with Crawford cover just about everyone working in the NBA.

“When you talk about an NBA referee, the first guy you think of is Joe Crawford,” said Mike Callahan, who has worked in the NBA since 1990. “Why? Because not only is he a great referee, but as a partner on the floor, he wants you to be even better than him. For the time I’ve been around the NBA, there is not a harder worker at the craft than Joe.”

The answer to the second question — why a gifted official who openly concedes that he tainted his career by periodic seismic outbursts received the highest honor in his profession — is a little more elusive. While the ugly side of Joe has been played out under the bright glare of NBA arenas and replayed ad infinitum for public scrutiny on ESPN, his passionate side has been a far more clandestine deal.

That Joe Crawford exists only in the shadows. That Joe Crawford will do anything for anyone he encounters who needs a helping hand or a sturdy shoulder, like the time he quietly picked up the $400 tab for a frightened young foreign lady stranded at an airport gate so she could fly back to her home country. Or the time he was there for a childhood friend named Jim Forrest.

“In 1986, I sought treatment for an addiction to alcohol,” said Forrest, a friend of Crawford’s since they were classmates at Cardinal O’Hara High School in Philadelphia from 1965-69. “When I was in treatment, Joey called my parents to find out what going on. My parents told him where I was and how long I might be there. Joey asked my parents if I needed help to pay for this treatment. He said just let him know and he would give them money for my treatment if it was needed.

“He was very supportive of me in my recovery. Whenever I would go to his house, he and his wife, Mary, would make sure there was iced tea for me to drink. He never judged or turned his back on me or anyone else.”

Perhaps the most powerful look into the side of Crawford so few get to see can be found on a reclusive dead-end street about a mile and a half from Route 1 in Alexandria, Va. There stands an older structure connected to a chapel, which houses cloistered Poor Clare nuns who have renounced their worldly lives. Their severely structured lives include sleeping on beds of straw, never for more than four hours at a time, rising in the middle of the night to pray, existing on bare essentials and having virtually no contact with the outside world.

One of those nuns is Sister Rose Marie. She was once Shelley Pennefather, the NCAA Player of the Year in women’s basketball for Villanova in 1987 who turned her back on a six-figure salary playing professionally in Japan to follow her heart into a spiritual life.

By special permission of the Mother Superior, Villanova Coach Harry Perretta has been granted brief access to his former star player every June for the past 22 years. Perretta, Villanova’s coach since 1979, can speak to Sister Rose when she appears at a screen and the experience has never been less than overwhelming for him.

“When I go there, there’s just a total sense of peacefulness,” Perretta said.

When the two chat, Perretta notices a profound spiritual presence interspersed with hints of her old sense of humor. Their conversation inevitably turns to Crawford, who she once knew as an official back in Pennsylvania and whom she now knows as a limitless source for charitable donations.

“I don’t know how much money he’s given to the Poor Clares over the years, but I know it’s substantial,” Perretta said. “He runs a referee clinic during the summer and I know the proceeds he gets from that he sends to them. He also sends money to me to give to her when I go visit. So he’s done a lot over the years.”

And Sister Rose Marie has never forgotten her flawed, yet treasured friend whom she got to know her first season at Villanova.

“She always asks how he’s doing,” Perretta said. “He is on her list and she prays for him, just like she prays for me. When things have not gone perfect for him, he’s said, ‘Let Shelley know so she can pray for me and hopefully everything will work out.’”

How can it possibly be suggested that it hasn’t for this most complex and misunderstood man? As he heads into the final stretch of an NBA career that started when he was 26, Crawford has worked more playoff games (300 going into this postseason) and Finals (49) than anyone in the league. He also has appeared in the Finals every year since 1986, except for the year he was suspended for the Duncan incident.

But the giant he has been in his profession for more than 35 years is dwarfed by the man so few ever get to see — a man who almost perfectly embodies the model of what a Gold Whistle Award recipient should be all about. And you’d better believe when Crawford was notified by Barry Mano, president of NASO, that he was this year’s recipient, he was reduced to tears.

“I was brought into NASO by Eddie Rush, our former boss,” said Crawford, referring to the NBA’s director of officiating from 1998-2003. “He used to tell me about going to the meetings and going to the conventions and everything. I said, ‘Ed, I have so much stuff going on in the summertime coaching kids and that kind of stuff.’ But then I went and I fell in love with the event every year. I’ve been to, I guess, six or seven, and I used to sit in the audience and I’d watch the presentation and I would say, ‘My Lord, have mercy!’

“I was pretty much of a pro official snob until I started attending these things and I found out about all these officials from all over the world and all these different sports and what their passions were and how they loved what they did. When I’d see this guy go up there and get this award … when Barry Mano called me, I still tear up because it’s like, ‘Man, oh man, these people are unbelievable. They’re all tremendous stories. And it never entered my head that, ‘Hey, Joe Crawford, one of these days, you’re going to get that thing.’ Honest to God, it never entered my head.”

Maybe, just maybe, Sister Rose Marie knocked one out of the park with her prayer power within the confines of her secretive quarters. For a man whose NBA career might have gone up in flames in 2007 has now been set in stone for what he is: an imperfect sweetheart of a guy at the top of his profession who manned up to his character issues and enhanced his already bottomless pit of a heart.

“Joey depicts what every official should strive to be,” said Jeff Triplette, an NFL referee and chair of the NASO board of directors. “That’s someone who got to the top of his game early, but always worked to stay at the top of his game and never stopped trying to improve. He always has been a caring and giving individual to lots of individuals, lots of organizations and has been very quiet in that regard, but had that hothead image.

“But he worked hard to change that and he’s worked hard to realize that just didn’t get him where he personally wanted to be. Some people who are at the top of their game might say, ‘Nah, I got here for who I am and they’re just going to have to accept me for who I am.’ But he said, ‘No, I need to change.’ He’s someone I call a friend, but I also admire him as someone you want to be like.”

Not too shabby at all for Crawford, who belies the image he may never completely shake by laughing easily and swerving effortlessly into self-deprecation during conversations. He considers his life to be an open book with twists and turns — no controversy in his career is off limits with him.

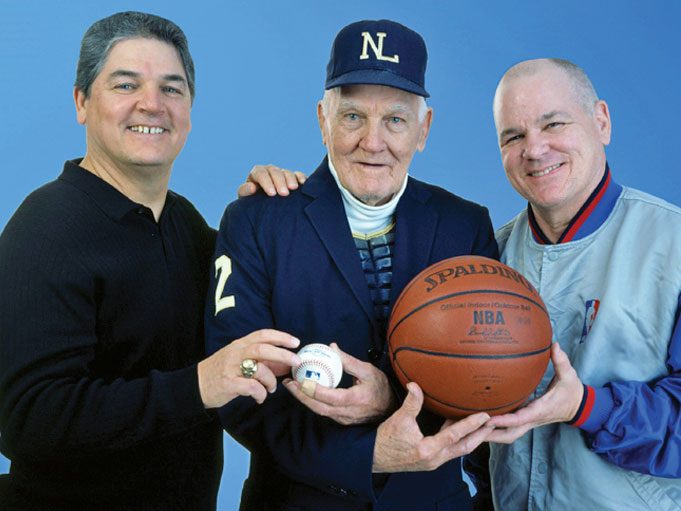

He was born Aug. 30, 1951, the youngest of four children to Henry and Vivian in Havertown, Pa., about nine miles west of Philadelphia. Henry “Shag” Crawford was five years away from breaking into the major leagues as an umpire for what turned out to be a 19-year career. Jerry Crawford, one of the two brothers he shared a room with in their tiny two-bedroom home at 1637 Frazier Ave. — Shag upgraded to a three-bedroom dwelling the year he broke into the major leagues in 1956 — followed in his father’s footsteps in the major leagues from 1976-2010.

Perhaps the seeds to what Joe would become, both as an elite NBA official and someone who cannot do enough for people, were planted in May 1965, just as he was about to graduate from the eighth grade at St. Pius XI Elementary School in Broomall, Pa. Sister Joanne was singling out students when she turned her attention to Joe.

“They were giving out awards and I wasn’t a great student,” he said. “I was far from that, to be honest with you. Back in those days, you had 60 kids in the classroom and she’s giving out all these awards and I didn’t expect to get anything — just like the Gold Whistle Award. And then she said, ‘We’re giving the effort award this year to Joseph Crawford. Joseph tries very hard and does very well in school and he has a low IQ.’

“I didn’t know what an IQ was, right? And I have this scroll to Joseph Crawford for the effort award and I go home and I’m happy as hell. I walk in the house and my mom says, ‘How did it go, Joseph?’ And I say, ‘Hey Mom. Guess what? I got the effort award. Sister said I got it because I’ve got a low IQ!’ Her mouth opens and she says, ‘You don’t have a low IQ!’”

Crawford was laughing as he mimicked his mother’s aghast reaction. But then he quickly regained his composure and isolated the impact he believes that one day nearly 50 years ago had on him.

“I don’t know whether it touched me where I had to prove for some reason that I have to do more effort-wise, that I have to put this time in,” Crawford said. “Like, I’m always in the gym working out, I’m constantly looking at the rules … I don’t know if it was because I was scarred, that someone said I wasn’t that intelligent.”

The mixed emotions he had for his father, who died in 2007 — just three months after the Duncan incident — also play into the man he would become. Shag was certainly generous with his kids. How about the time he gifted Jerry with a glove worn by Willie Mays while Joe got one of Ken Boyer’s gloves? Or the box of more than 100 major league baseballs for the neighborhood boys to use at the vacant lot?

But Shag could also be a distant man, both in his marriage and with his kids, who also included daughter Patti, the eldest, and Henry. That was never more evident to little Joe than on Oct. 3, 1963, at Yankee Stadium when the Los Angeles Dodgers took a 2-0 lead in the World Series over the Mantle-Maris New York Yankees. The Series was shifting to Los Angeles and Joe can still feel the emptiness of all but being abandoned by his dad after the game.

“My sister and I were waiting after the game and my father’s passion was a little misplaced, to be honest with you,” he said. “They were leaving directly after the game in New York and flying to L.A. He comes out with the other umpires and they were going to get in a cab and go to the airport.

“We say, ‘Hey, Dad!’ and he comes over and hugs us, but two seconds later, he’s in a cab. That has stuck with me my entire life. I talk about that with my sister. She asked, ‘What would you have done?’ I said, ‘I would have gone back to Philly with my kids, I would have gotten my kids home and then I would have flown from Philly to L.A.’ As I look through the years, I think, ‘I get it, Dad, with your profession.’ His passion was off the charts and he gave it to me and my brother. I get that. But those kinds of things he was pretty inept at.

“I love my father to death. I just think he could have done some things a little more fatherly.”

Maybe that explains why Crawford has been a loving husband to Mary for 42 years, a devoted dad to daughters Amy, Megan and Erin and a world-class grandpa to nine grandchildren. And maybe that explains why Joe is always the life of family functions.

“To our family, Joe is revered,” Jerry Crawford said. “Everyone in our family loves Joe and there’s a reason for that. Joe is a kind and gentle guy and he takes time to have fun with everybody. And he’s very, very generous with the family.”

The question begs to be asked: Why was he such a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde for so many years? Why did such a compassionate man so often simply lose it within the confines of arenas — to such an extent that he consulted a psychologist? Looking back on it, Crawford surmises that he had such a passion for his profession that he simply would not tolerate any disrespect — to the extent of tarnishing his own image.

“It always makes me laugh that people who have never done this actually believe that just because they watch, they know what you do,” Crawford said. “As the years have gone by, I understand it now — that’s being a fan, that’s being a coach, that’s being a player, whatever. But in all those years when I was dealing with those anger issues, and still do, I think that was the crux of the matter. I just couldn’t understand people who don’t know a thing about it but actually holler at you.”

Crawford finally bottomed out with the Duncan episode. He remains haunted by the sheer ugliness of that afternoon, but he also started re-inventing himself during those long months before Stern reinstated him in time for the 2007-08 season.

“I knew then that I had to do something,” Crawford said. “That wasn’t good. That, again, was the macho thing where I’ll prove I can do it and I did it. It wound up biting me in the ass. I haven’t been happy with myself since I did that. That was the low mark, the real, real low mark of my career.”

But with his demons finally locked away, we can truly celebrate the man and the official he is as the passing of time erodes the stuff that wasn’t as pleasant. What can be said with certainty is that Crawford hurt only himself when his temper got the best of him, but that he has helped more people than anyone — even Crawford himself — will ever know.

“I was working on a playground one summer night back in 1986,” said Mark Wunderlich, an NBA official from 1990-2010. “A lot of players were complaining on every call. A man walked across a creek adjacent to the court following the game. I figure, ‘Here comes another guy to vent his frustration at my limited skill set.’

“He said, ‘My name is Joey Crawford, I just worked the NBA Finals and I have been watching you out of my kitchen window all summer. I think you should try and pursue NBA refereeing. You have no idea what you are doing, but I see something I like.’

“He changed my life in one conversation with a glance and a feeling I could become an official in the NBA. He saw something in me I did not. Someone he had never talked to. I owe him everything for taking the time to change my life.”

Crawford has simply had a way of turning up at so many places over the years and leaving a lasting impression with a style that has to be seen to be believed.

“I used to see him at all the local gyms in Delaware County, Pa., where we both resided,” said John DiDonato, Crawford’s attorney and close friend since the early 1990s. “Sometimes, Joe was there as a fan or to observe a young official. Sometimes, he was helping coach a team of young girls. No matter what the reason for his presence, you could be assured of one thing — this guy was loud, opinionated and manic.

“Joe would jump up and down, exhorting everyone to do better. He would encourage and cajole the players and referees into performing at a higher level. Somehow, some way, by telling people what they did wrong, Joe made everyone feel good about themselves. The kids loved him, the young referees were in awe of him and the parents were thrilled to have him around.”

Like DiDonato, whose daughter played in grade school back in those days.

“I am here to tell you in the simplest way possible that Mr. Crawford is a kind, gentle and considerate soul, a man who would give the shirt off his back to anyone who needed it,” DiDonato said. “What higher praise could be bestowed upon anyone, especially a public figure?”

Ask any referee about Crawford’s mastery on NBA courts for 37 years and they will be effusive. But the greatest praise for Crawford is not for his accomplishments in NBA arenas, but rather for who he has emotionally touched in his everyday life.

It’s in the shadows, NBA official Monty McCutcheon said, where Crawford has truly been at his best.

“From hotel employees to van drivers to the neighborhood parish in which he was raised, Joe has been a selfless giver who is quick to make those working hard for a living feel included, validated and welcomed through his sense of humor and questions about their lives,” said McCutchen, who has worked in the NBA since 1993. “I’ve seen the neighborhood corner shoe repair man, ‘Lou the Shoe,’ have a lighter step when Joe walks in with shoes. I’ve seen a young referee’s demeanor change for the better when Joe Crawford offers words of encouragement.”

“I’ve seen it so many times that it has become clear to me that this is the totality of the man and the public ideas about him are more shadow than substance.”

To be sure, this year’s Gold Whistle Award recipient is one misunderstood guy. And that’s just fine because as Ralph Waldo Emerson once said, “To be great is to be misunderstood.”

What's Your Call? Leave a Comment:

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.