This past summer I had the opportunity to attend an evaluation camp for umpires looking to advance their collegiate careers. The camp schedule called on each umpire to work two games each day — one on the plate, one on the bases. Each set of games featured an evaluator who would provide both verbal and written feedback on areas where improvement was needed.

On the afternoon of my second day, I found myself behind the plate and being evaluated by a longtime NCAA umpire who also happened to be a retired member of law enforcement. Early in the game, he had to be wondering whether he had signed on to write up an umpire evaluation or whether he was back on the highway ticketing impaired drivers.

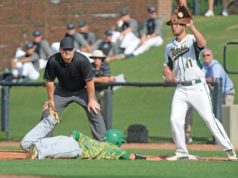

With nobody on base, the batter lifted a fly ball to left field that I initially read as routine. As such, I made my way up the third-base line a few steps into fair territory for what I figured to be a standard catch/no catch ruling. However, after just a few steps, two competing thoughts entered my head.

First, I remembered hearing this same instructor earlier in the camp mention to another umpire the need to avoid being straight-lined on fly ball coverage. Eager to show that I had been paying attention, I adjusted my route up the line and moved into foul territory to create an angle on the left fielder’s play on the ball.

But wait! It had turned into a windy afternoon in suburban Indianapolis, and after two or three steps in foul territory, I noticed the ball blowing hard toward the foul line. Angle be damned — I was going to have to make a fair/foul ruling. So back to the right I ran, putting myself in position to make the out call on a ball that ultimately stayed fair by about 10 feet.

At the end of the half-inning, I drifted toward the backstop to pick up any immediate feedback the evaluator had for me. I was met with a hearty chuckle from evaluator No. 1 as a second evaluator described my drunken escapade along the third-base line.

Finally, after he stopped laughing, evaluator No. 1 cut to the chase: “What is your first responsibility?”

It was a welcome lifeline, because it was a question I knew the answer to without hesitation.

“Fair/foul.”

He nodded his approval and on we went.

My particular play was not unique. In every baseball game — especially those utilizing the two-umpire system — there are several occasions where the umpires have multiple responsibilities on any given play. It’s rare any umpire has the opportunity to focus on one thing and one thing only when the ball is live, and even what appears to be a routine fly ball to the outfield with no runners on base might set the stage for a flurry of decisions.

Fortunately, we have a road map to help us prioritize the decision-making process. Some umpires refer to it as the order of operations. The actual instructional terminology labels it the “progression of responsibilities.” It’s something that should be drilled into every umpire during training classes at the outset of one’s umpiring career.

However, a quick reminder in a national magazine devoted to all things officiating is never a bad idea, either.

The progression of responsibilities for high school baseball umpires is found on page 11 of the 2019-20 NFHS Baseball Umpires Manual under the heading “Responsibilities During a Game.” Article 6 reads:

“On every batted ball the progression of responsibilities is as follows:

Fair or foul;

Catch or no catch;

In play or out of play;

Awarding bases.”

While such wording is not found in the NCAA or pro baseball rulebooks, this is the accepted progression at all levels of baseball umpiring. It gives umpires a flowchart for breaking down situations and for knowing the specific attributes of a play that must be focused on and understood before moving to the next step.

The beauty of this progression is in its simplicity. Perhaps if an umpire tried hard enough, he or she could find a play or situation in which this order of operations comes up short. However, let me illustrate an example offered up by a co-worker to show how the progression makes sense even on a play when all hell breaks loose:

There are two outs, a runner is on second base, and the batter hits a bounding ball toward the shortstop, who takes a couple steps forward from his starting position to field it. R2 crashes into the shortstop and the base umpire, working in the “C” position, immediately rules interference on the baserunner and calls him out for the third out of the inning.

Chances are, the umpire in this situation is not consciously thinking about the progression of responsibilities when arriving at this ruling. Instead, the first thought is most likely, “Uh oh, we’ve got a collision, now who is responsible? Is the fielder protected or is the baserunner? Is this interference or obstruction?”

The reason the umpire can go directly to that train of thought is because he or she has, subconsciously, already checked off items (a), (b) and (c) from the progression. There is no question this is a fair ball, so cross off (a). There is no question this is not a catch, so cross off (b). As soon as the collision happens in this scenario, we know the ball is dead, so cross off (c). All that’s left to determine is the awarding of bases — is this interference and the runner is ruled out for the third out of the inning, or is this obstruction, with the runner and batter-runner awarded the proper bases (d)?

Now, let’s look at things from the complete opposite end of the spectrum. In a game using the two-umpire system, with a runner on second base and no outs, the batter hits a long fly ball down the left-field line. This happens on a field where there is almost no foul territory in play near the foul pole and a short, waist-high fence separating the playing field from dead-ball territory.

The first thing the home-plate umpire needs to know is whether this batted ball is fair or foul (a), as that will lay the groundwork for every additional decision on the play. For instance, let’s say the umpire rules it is a foul ball, it bounces off the left fielder’s glove in flight and it goes over the fence. Knowing it is foul first (a) and no catch second (b) lets us know (c) and (d) are irrelevant.

However, let’s say we have the same exact situation to start, the same fly ball and the first determination by the home-plate umpire is it is a fair ball (a). The left fielder catches the ball (b) and remains in the field of play (c). Did R2 legally tag up at second base and advance to third? Did he leave early? Is he 50 feet away from returning to second base as the throw comes back into the infield (d)?

Now, think about all of the possible wrinkles if anything after (a) changes in this last example. What if the left fielder makes the catch (b) but tumbles over the short fence and falls into dead-ball territory (c)? What if the left fielder does not make the catch (b) and the ball bounces over the outfield fence in fair territory or the short fence in foul territory (c)? Where do we place the runners in each of the scenarios (d)?

One can see quite clearly how this can become a challenging endeavor, with plenty of different rule citations to keep straight. Baseball is full of such challenges that make it a difficult game to umpire. Knowing that going in, we need to find ways to simplify the game where possible.

If you know your progression of responsibilities, no matter how wacky a play may become, you will have a solid roadmap for arriving at the proper final destination, with no weaving in and out of lanes required.

What's Your Call? Leave a Comment:

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.