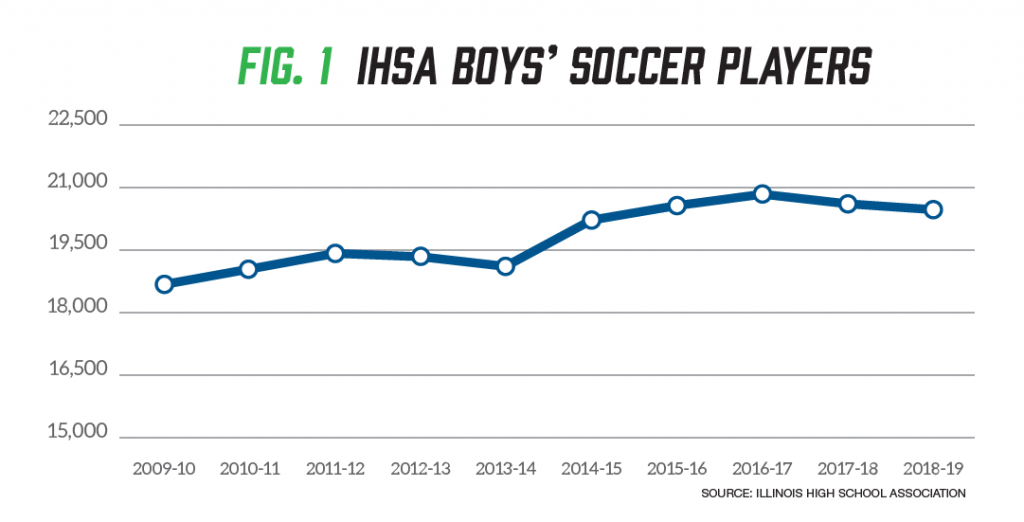

The NFHS reports a 16 percent increase nationally in the number of boys playing high school soccer in 2018 compared to 2009. While this may thrill soccer enthusiasts, it’s causing an unexpected problem. High school soccer is gaining games and there are not enough referees to support the growth.

Unfortunately, the NFHS does not publish national data on high school soccer referees. Therefore, an analysis is required of a state that publishes information on both players and referees. The Illinois High School Association (IHSA) has this information and it experienced a comparable increase of 13 percent in boys’ high school soccer participation since 2009. Examining the problem on the state level yields an understanding of the entirety of the problem and brings solutions to light.

In 2018, almost 2,500 more boys played high school soccer in Illinois than in 2009, as shown in Figure 1. Because schools can only field one varsity team, they added more non-varsity teams to accommodate these players. Chicago suburban schools now typically carry five or six boys’ soccer teams. This places strain on officials and local assigners who noted a 12 percent increase in the number of high school boys’ games since 2014.

In 2018, almost 2,500 more boys played high school soccer in Illinois than in 2009, as shown in Figure 1. Because schools can only field one varsity team, they added more non-varsity teams to accommodate these players. Chicago suburban schools now typically carry five or six boys’ soccer teams. This places strain on officials and local assigners who noted a 12 percent increase in the number of high school boys’ games since 2014.

Data now validates the observations of the assigners. According to the IHSA, the same amount of referees had been officiating more boys’ soccer players through 2017. But then something happened: Illinois lost soccer referees.

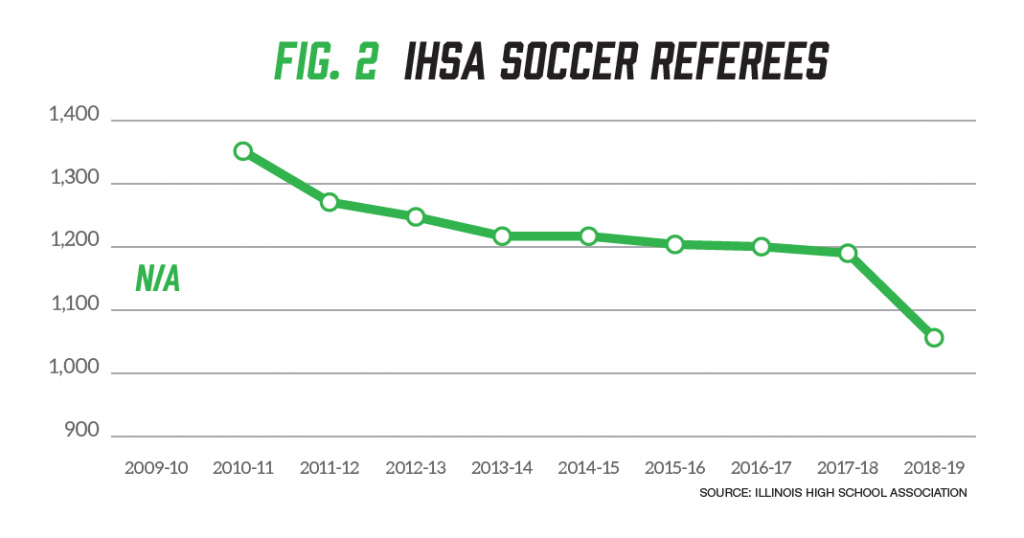

Illinois lost 11 percent of its high school referees in 2018-19 and 6 percent more the next year, as shown in Figure 2. Why were referees leaving and why weren’t they being replenished? It’s a question that was being explored — and then something significant happened: the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

Illinois lost 11 percent of its high school referees in 2018-19 and 6 percent more the next year, as shown in Figure 2. Why were referees leaving and why weren’t they being replenished? It’s a question that was being explored — and then something significant happened: the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

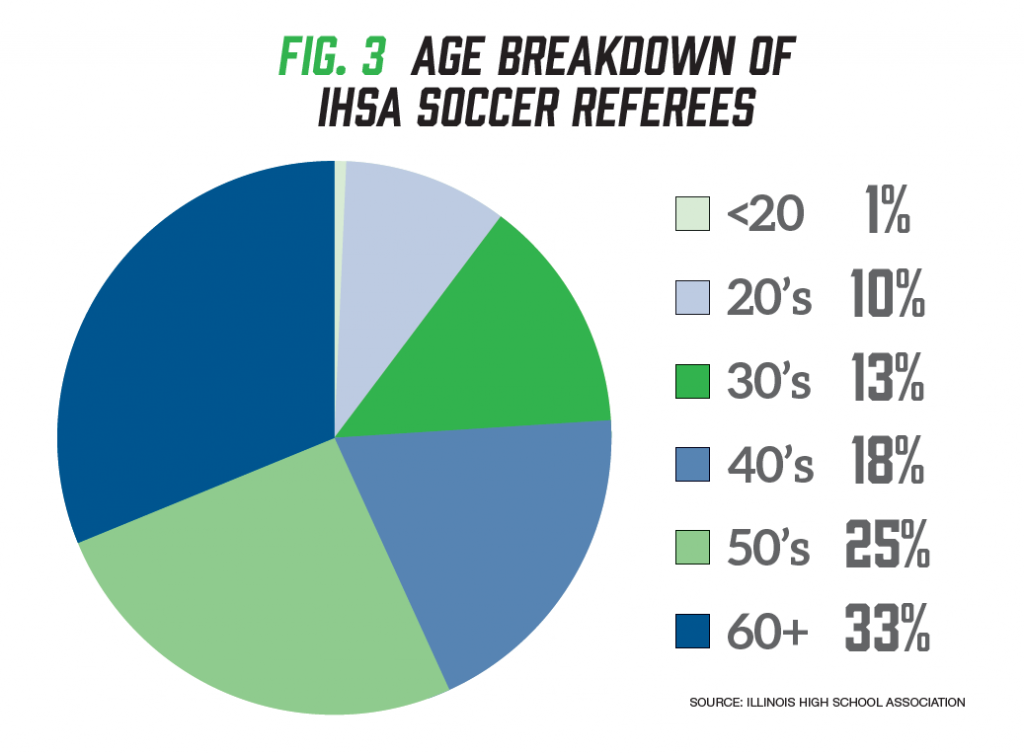

The demographics of sports officials tend to skew older and IHSA soccer referees are no exception. Nearly 60 percent are 50 or older; 33 percent are 60-plus, as shown in Figure 3.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, meanwhile, indicates the risk of severe illness, hospitalization and death from COVID-19 increases with age. Recommendations that older individuals take more precautions amid the pandemic could mean fewer will officiate.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, meanwhile, indicates the risk of severe illness, hospitalization and death from COVID-19 increases with age. Recommendations that older individuals take more precautions amid the pandemic could mean fewer will officiate.

Older referees were a linchpin to short-term solutions to staffing games while associations recruit and train their replacements. The simplest short-term solution was to assign fewer officials per game and to further stagger the start times to help officials cover two games per day. But this won’t work if there are fewer referees.

How many referees might be lost and what’s the impact?

Results from a May 2020 NASO survey of sports officials on the return to officiating amid the pandemic offer discouraging insights. Nearly 20,000 officials responded to the survey nationally, including 1,000 respondents from Illinois. The Illinois responses were similar to the overall national responses.

Approximately one-third of officials indicated they would not be comfortable returning to officiate amid the pandemic. High school soccer was already in the midst of a referee shortage. Losing an additional third of officials would be untenable. Forty-four percent of officials identified the most important determinant to returning to officiate is either a vaccine or widespread testing — neither appears imminent. Reducing soccer officials by 30-plus percent would likely result in fewer scheduled games and could lead to fewer students participating in soccer. COVID-19 may have changed the referee shortage from a tomorrow problem to a today problem.

Before referee numbers began shrinking, soccer had been experiencing a growth in boys’ soccer participation. Interestingly, the increase has not been driven by population growth. In a recent study, a Chicago suburban newspaper, The Daily Herald, reported declining suburban populations each year since 2014. Does this mean soccer suddenly became more popular? No. If that were the case, participation in girls’ soccer would have grown comparably, but it did not. Therefore, something else has driven boys to soccer.

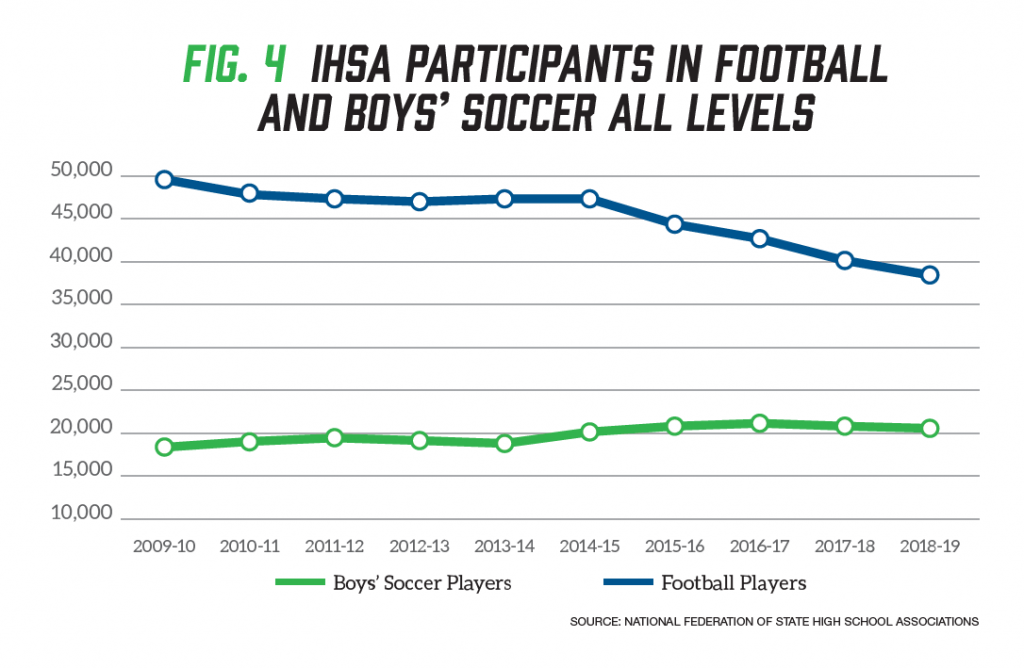

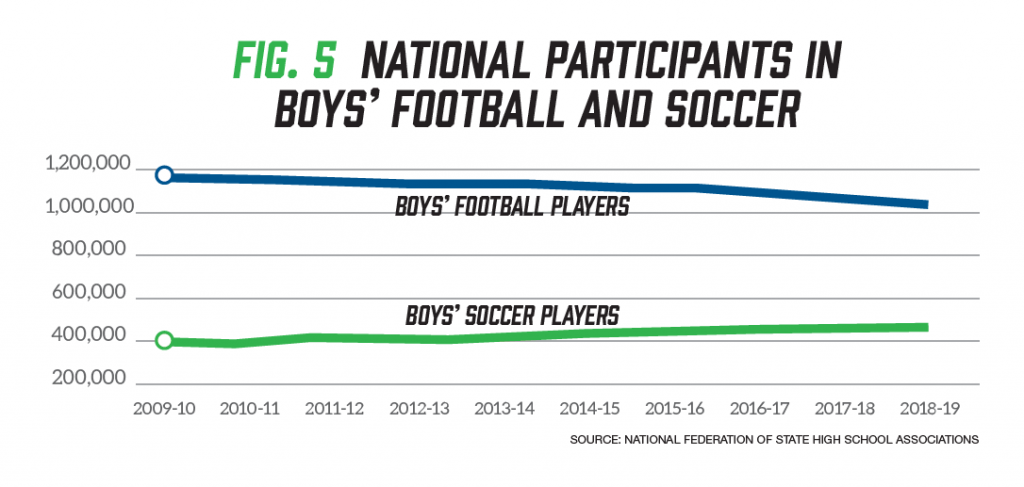

A correlating decline in high school football participants is likely a major source of new soccer players. From 2014-18, more than 8,500 fewer students played football in Illinois. This prompted The Daily Herald to study football participation in Chicago suburban high schools. It reported an 18.7 percent drop in participants since 2008, attributing the decline to concerns about concussions. “The biggest drop came in 2016, eight months after the movie ‘Concussion’ hit the theaters. Suburban schools combined to lose 903 players from the previous season,” the paper reported.

As Figures 4 and 5 show, many of these football players migrated to the soccer field both in Illinois and throughout the country.

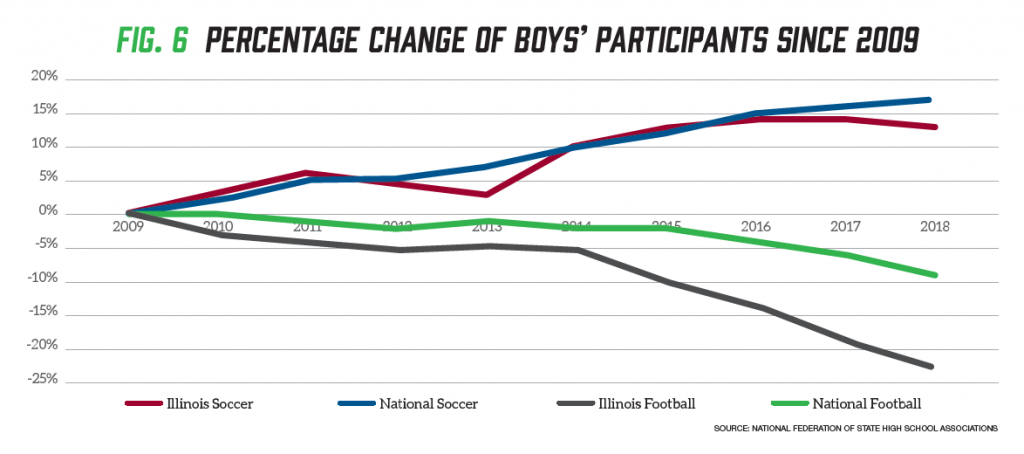

What the charts reveal is not nearly as interesting as what they imply. For example, the decline in football is less pronounced nationally than it is in Illinois. From 2009- 18, the national decline in football participation was only 9 percent while it reached 19 percent in Illinois. If the national decline reaches the Illinois rate of 23 percent, 163,000 more students across the nation would leave the football field in search of another activity. Additionally, the increase in soccer players is sharper nationally than in Illinois.

What the charts reveal is not nearly as interesting as what they imply. For example, the decline in football is less pronounced nationally than it is in Illinois. From 2009- 18, the national decline in football participation was only 9 percent while it reached 19 percent in Illinois. If the national decline reaches the Illinois rate of 23 percent, 163,000 more students across the nation would leave the football field in search of another activity. Additionally, the increase in soccer players is sharper nationally than in Illinois.

To better understand the relationship between participation in the two sports, see Figure 6. It reflects the percentage change of participants in each sport on a state and national level. As athletes left football, athletes took to the soccer field. In fact, the percentages of change in Illinois between the two sports almost mirror each other. The chart also shows the discrepancies in the rates of change between the nation and Illinois. Imagine the implications for soccer referees if the national decline in football participation reaches the Illinois pace.

To summarize, if the national decline in football reaches the Illinois pace, states have problems. And if more states follow the national increase in soccer players, states have problems. What states don’t have is proven, long-term solutions. The solution starts with a better understanding of the problem.

For years, people have concluded the problem is officials are quitting. We now know the shortage is caused, in part, by increasing players. And for years, states have maintained that abuse is driving referee attrition and stagnation. Yet states like Illinois have never conducted an exit survey to validate that conclusion.

For years, people have concluded the problem is officials are quitting. We now know the shortage is caused, in part, by increasing players. And for years, states have maintained that abuse is driving referee attrition and stagnation. Yet states like Illinois have never conducted an exit survey to validate that conclusion.

The NASO National Officiating Survey in 2017 received responses from 3,725 soccer referees on which level of soccer demonstrated the worst sportsmanship. Only one in six respondents cited high school soccer. Therefore, it does not make sense that abuse is necessarily driving referees away from high school soccer to officiate soccer at other levels.

Does that mean states should simply recruit more officials? Surprisingly, no. States don’t need to attract more officials; they need to retain the ones they have recently recruited.

In Illinois, an average of 235 new high school soccer referees enrolled each of the past four years. That number is sufficient to replenish attrition in a state with a recent history of 1,200 active high school soccer referees. Yet in Illinois, and across the nation, it’s commonly thought that nearly two-thirds of new officials drop out within three years.

The question is why? People point toward abuse, but assigners cited other factors that push referees away from high school soccer. These include early weekday game times that conflict with work, the inability to obtain desired game assignments and poor comparative compensation. In the NASO survey, 60 percent of soccer respondents indicated money did not play a role in their decision to become an official. However, the study failed to inquire if money was a factor in choosing which soccer games to officiate.

Ted Campbell, an assigner in Springfield, Ill., said high school referees are paid a total of $80 for officiating both a JV and varsity game on the same day. Alternatively, those referees can earn $120 as an assistant referee for a college game. Why would someone choose two high school games when one college game offers 50 percent more pay in 50 percent less time?

Retaining officials doesn’t only entail increased pay, later game times and better assignments, it requires understanding people better. The NASO survey revealed that more people are entering officiating after age 40, unlike a previous generation of officials who began as teenagers. These two age groups require different types of support to address distinct motivations and challenges.

Older referees may feel a desire to give back to the community and are less deterred by on-field hostilities. Younger referees might be motivated by both money and opportunities to officiate challenging games. Retaining them may entail higher pay and guidance from mentors in dealing with challenging situations. The average age of a referee who quits is 41, according to IHSA data. This means retention efforts need to be targeted to this age demographic.

State associations can help their retention efforts by asking new officials about their motivations and expectations. Then states can continue to communicate with newly licensed officials to learn what they need to stick with it. If they leave, states need to find out why and then adapt. NASO has developed an entire set of resources to help retain officials.

Solving the referee shortage starts when all stakeholders understand the totality of the problem and begin to work together. It’s daunting and it calls for leaders to be optimistic and willing to try. Those two attributes describe an American president who led our nation through economic challenges similar to the ones faced today. The words of Franklin Delano Roosevelt are still relevant: “Take a method and try it. If it fails, admit it frankly, and try another. But by all means, try something.”

What's Your Call? Leave a Comment:

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.