It is June 14, 1998, at the Delta Center in Salt Lake City. The Chicago Bulls are playing the Utah Jazz in Game 6 of the NBA Finals. Dan Crawford is one of the referees.

The Jazz are leading by one with the ball, 20 seconds away from forcing a Game 7 at home. Utah’s Karl Malone sets up in the low post on the left side of the lane. Teammate Jeff Hornacek, guarded by Michael Jordan, runs to the right corner, drawing Jordan away from the play. Crawford is on the baseline.

“Michael peeked back and saw the pass go into Malone,” says Crawford.

Jordan sneaks along the baseline and slaps the ball away from Malone, his fourth steal of the game.

“That’s a pressure cooker,” says Crawford, who had a clean look at the play. “Michael hit all ball. The ball went straight down (and up to him).”

Utah’s Bryon Russell is shadowing Jordan as he dribbles up court. Jordan starts driving to his right, pulls up, puts out his left arm to fend off Russell and pours in a jumper with 5.2 seconds to play.

The Bulls win 87-86, Jordan’s sixth and final championship.

But did Jordan shove Russell away to clear room for the winning shot?

“Did he push off ?” says Crawford, 20 years later. “You tell me.

“Fifty percent of the people will say he did, and 50 percent say he didn’t.”

Crawford is located on the right side of the court on the play.

“Michael stuck out his left arm,” says Crawford. “The official on the other side of the court (Dick Bavetta) had the best view. The call belonged to him.”

No whistle.

Some NBA fans who believe that Jordan pushed off and don’t know anything about officiating have suggested star treatment — no way a referee is going to call a foul on the great Michael Jordan on the deciding play.

“We really don’t think that,” said Crawford, now 65 and living in Naperville, Ill. “The referee has to make the call in two-tenths of a second.” There is obviously no time to determine which player should get the benefit of a foul call.

Crawford is focused on Russell on the play.

“The fans look at the guy with the ball all the time,” he says. “The referee is looking at everything else. I’m looking at the defensive guy. You’re a fan, the coach is the coach and I’m the referee. We’re looking at three different games. It’s totally different.”

Jordan scores 45 points in the game. Toni Kukoc, with 15 points, is the only other Bull to reach double figures.

“It was a classic,” says Crawford. He adds that the excitement of the game does not influence how you referee. “You don’t open yourself up to ‘this is a great game’ because it can scare you. The ideal thing is to treat all games the same. (As an official) you don’t turn the volume up or down.”

Crawford remembers the crowd being intense, even for the NBA Finals. He names Utah and Portland as the toughest places to referee in the league, maybe because the NBA is the only one of the four major sports in those two cities.

“You block out the crowd, the way a foul shooter won’t see the people in the crowd behind the basket waving their thunder sticks,” he says.

Virtually everyone involved is exhausted after the decisive game.

“You’re so mentally drained,” says Crawford. “You don’t sleep well.

You’re still wired from that game. The pressure is so great.”

It is two days before Crawford watches a replay of the game. How did he do?

“I could watch the video and pick up something I didn’t call,” he says. “You have to put it behind you. There’s never been a game where the referees were perfect. The key is to not make a mistake down the stretch. I was pretty good down the stretch in that game.”

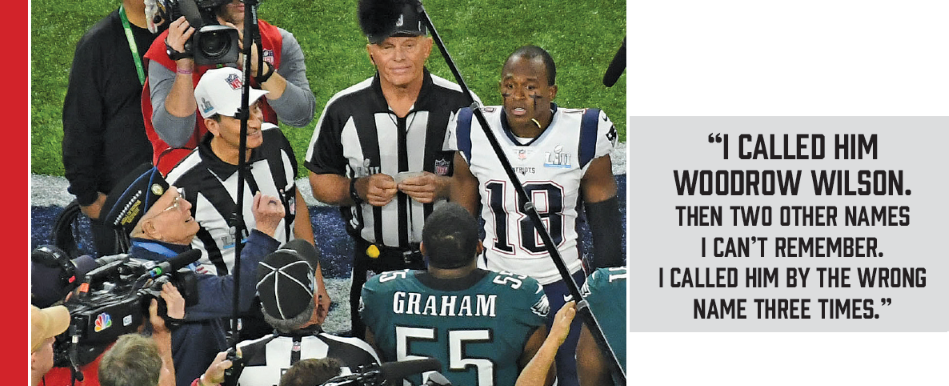

It is Feb. 4, 2018, Super Bowl Sunday at U.S. Bank Stadium in Minneapolis. The Philadelphia Eagles are playing the New England Patriots.

Gene Steratore learns after the conference championship games, two weeks ago, that he has been chosen to referee Super Bowl LII. “It’s humbling,” he says. Referees face similar challenges as the players in preparing for the Super Bowl. They spend hours obtaining tickets and helping to arrange travel plans for loved ones who want to attend the game.

“I needed tickets for 22 Italians,” says Steratore. “Not all of my seven brothers and sisters were able to attend, thank God. You can’t get hotel rooms (Super Bowl week) for $89 or with Marriott points. We had a whole wing at the hotel.”

Officials try to act as if every game is the same. But deep down they know it’s not. This isn’t just another game. It’s THE SUPER BOWL!

“You can’t treat it like any other game,” says Steratore. “It’s not realistic.”

Steratore admits to being nervous taking a shower the morning of the game. He is not worried about blowing a call. He is not worried about making a mistake at a crucial time. Would you believe he’s worried about the coin toss?

He rides a shuttle bus to the stadium, arriving 3-and-a-half hours before kickoff. Now his nerves are fine. “That buildup is a calm, relaxed feeling,” he says. “You’re comfortable and confident. The coin toss is the only part that’s scripted.”

The NFL is honoring 94-yearold Woody Williams, one of the few surviving Medal of Honor winners from World War II, at the coin toss. Steratore blows the script.

“I called him Woodrow Wilson,” says Steratore. “Then two other names I can’t remember. I called him by the wrong name three times.”

“I called him Woodrow Wilson,” says Steratore. “Then two other names I can’t remember. I called him by the wrong name three times.”

Fortunately, the rest of the day goes much smoother for Steratore and his crew. There are only seven penalties enforced for a grand total of 40 yards in the game. The Patriots are flagged just once for five yards. It is a clean game.

“They say the refs put the flags in their pockets in the postseason,” says Steratore. “I think the players subconsciously don’t want to make a mistake. They said later, ‘You did a great job. You let them play.’ They just didn’t foul.”

The Eagles and Patriots are both moving the ball at will. There is only one punt in the entire game. Philadelphia quarterback Nick Foles, filling in for the injured Carson Wentz, is having a superb day. So is Tom Brady.

Late in the second quarter the Eagles are leading 15-12 and facing a fourth-and-goal at the New England one yardline, just 38 seconds left in the half. Steratore anticipates the Eagles will attempt a field goal. “Mentally you’re putting the kicking ball on the field,” he says. But the Eagles line up to go for it with Foles in the shotgun.

Foles begins to walk toward his center, then pauses. He breaks outside and there is a direct snap to Philadelphia running back Corey Clement. “Did he get set?” Steratore asks himself. “I hope all of that was legal.”

Clement pitches to tight end Trey Burton, who finds Foles alone on the right side of the end zone and tosses him a pass. Touchdown! Eagles lead 22-12.

Steratore, who is 55 and lives in Washington, Pa., near Pittsburgh, knows he makes the right decision by not calling a foul on Foles.

“You don’t get to where you need to be as a ref in terms of experience until about your late 40s or 50,” says Steratore. “It’s a lot of years. You should be at your peak. About then Father Time kicks in. You have to push your body. You have to have the ability to concentrate and focus.”

The Eagles go for another fourth down in the fourth quarter. They are trailing 33-32, facing a fourth-and-two from their own 45 with 5:39 to play.

Foles goes through a long count. “He’s not going to snap it,” thinks Steratore. “They’re going to milk it to a second or two, then call timeout, or take (a delay of game) penalty. I have to ask Coach Belichick if he wants to accept it.”

It’s the biggest play of the game. If the Eagles don’t make it, New England will have the ball, the lead and the momentum.

“Of course, there’s pressure,” says Steratore, insisting he is comfortable and relaxed. “It’s what you do with the pressure. You either swallow it or embrace it. It becomes your best friend. Sometimes I laugh too much on the field.”

The ball is snapped and Foles completes a two-yard pass to Zac Ertz for the first down. Seven plays later Foles connects with another pass to Ertz for an 11-yard touchdown. Philadelphia goes on to win 41-33.

The teams combine for a Super Bowl record 1,151 yards of total offense. Brady throws for 505 yards and three touchdowns. Foles completes 28 of 43 for 373 yards, throws three touchdown passes and catches one more.

Steratore doesn’t watch a tape of the game for two months.

“I know things went OK,” he says. “I didn’t see anything that (we missed that) jumped off the screen. This is really an exciting game, which you don’t think about during the game.”

It is Aug. 20, 2002 and the WNBA is becoming firmly entrenched as a professional league, now in the playoff s of its sixth season. The Houston Comets, who won the championship the first four years, are facing the Utah Starzz in the deciding game of a best-of-three playoff in the Western Conference semifinals at the Compaq Center in Houston, formerly known as The Summit.

Lisa Mattingly is one of three referees working the game. This is not going to be just another game, not even just another playoff game. This is a game that Lisa Mattingly will never forget.

During a timeout early in the second half, Mattingly and fellow referee Roy Gulbeyan look over to the scorer’s table and see their third official, Bill Stokes, lying on the ground. He has suffered a heart attack.

The noisy arena, with 9,540 fans present, falls silent. The Comets’ trainer and team doctors go to work on Stokes right away. “Thankfully they had an AED (automated external defibrillator) there,” says Mattingly. They use paddles to shock Stokes’ back to life. Eventually he is loaded onto a stretcher and wheeled off the court. Mattingly and Gulbeyan follow.

“They closed the door in our face,” says Mattingly, upset she can’t stay with her fellow official.

Stokes, who has been a referee in the WNBA since the league begins in 1997, is taken to Memorial Hermann Southwest Hospital.

“The game was on national TV,” recalls Mattingly. “It went off the air. My voicemail blew up.”

Val Ackerman, president of the WNBA, is at the game. She has a difficult decision to make. Finish the game now or suspend it until a later date. There is 15:33 left to play.

“They had a timetable to keep,” says Mattingly. “There are only so many days the arena is available and this is the playoff s. We’re told we’ve got to finish the game. They took some heat for it. Val did what was best for the league.”

Ackerman leaves the arena to be with Stokes.

The players would probably have preferred to go home. Same with the referees.

“We didn’t want to do it,” says Mattingly, worried about her friend Stokes. “It was very hard. I didn’t know if I could do it. I was a mental wreck.”

Everyone is back on the court. “All the players were in tears,” remembers Mattingly. Someone begins reciting the Lord’s Prayer and the crowd stands in unison and joins in. “It brought some humanity to the game,” she says.

Twenty-five minutes later the game resumes with Mattingly and Gulbeyan as the only two referees. “I hadn’t worked a two-person crew in years,” she says. “I was all over the court to start, but we finally got settled in. We finished the game under duress. It was very hard. It’s about like being in a car wreck.”

Utah wins, 75-72, to advance to the Western Conference finals vs. the Los Angeles Sparks, the eventual champions.

Mattingly goes immediately to the hospital to check on Stokes. He is in critical condition. She begins calling Stokes’ family and friends. She and Stokes have been friends for a decade and referee many college games together, as well as WNBA games.

Mattingly must work another playoff game days later in Utah. But she returns to Houston to visit Stokes in the hospital.

Ten days after the heart attack, Stokes, after undergoing bypass surgery and having a defibrillator installed in his chest, is released from the hospital, but he never officiates again.

Mattingly, one of the top female officials in the country, continued to referee for another 16 years. The last game she worked was the 2018 women’s Final Four. After 28 years as an NCAA Division I referee, plus 10 years in the WNBA, she retired to become supervisor of officials for the SEC, WAC, Sun Belt, Southland and Atlantic Sun conferences.

Mattingly, now 56, has homes in Clearwater, Fla., and Nicholasville, Ky. She says for the first month or two, when she attends college games as a supervisor, she will probably bring her official’s gear along, “just in case they need a third referee.”

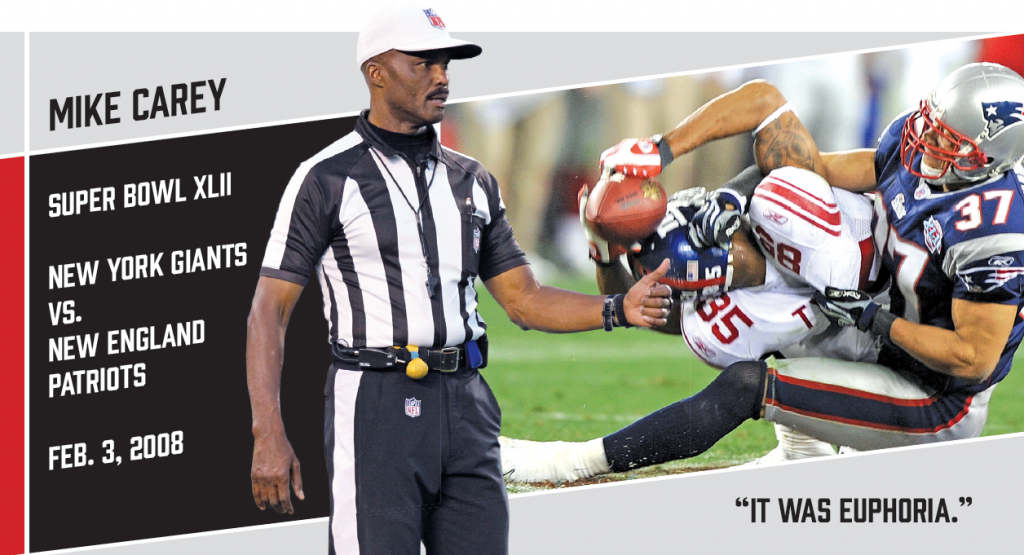

It is Feb. 3, 2008, in Glendale, Ariz. The New England Patriots are attempting to become the second undefeated team in pro football history, matching the 1972 Miami Dolphins, by beating the New York Giants in Super Bowl XLII.

Mike Carey is the referee for what will become one of the most memorable games in Super Bowl history.

“It’s a completely different environment,” says Carey. “You get there four days early. There are a lot of activities that the NFL provides. You’re not with your regular crew. (The NFL chooses top-rated officials at each position.) It’s time to get to know each other.

“It’s the only game of its kind. The eyes on you are memorable. You try to work every play like it’s the last play of the Super Bowl. But once the ball is kicked off , it’s like any other game.”

An estimated 97.5 million will watch the game on TV, in addition to the 71,101 in attendance. That’s a lot of eyes on the referee.

Carey has been a part of some wild games. He was the side judge in a January 1993 playoff game when the Houston Oilers led Buff alo 35-3 early in the third quarter and the Bills rallied to win, 41-38, in overtime, the biggest comeback in NFL history.

New England, at 18-0, is a 12-point favorite over the 13-6 Giants in 2008. “I learned long ago that doesn’t mean anything,” Carey says of the betting line.

Tom Brady completes a touchdown pass to Randy Moss with 2:42 left to give the Patriots a 14-10 lead. Carey is prepared for the Giants to make a long kickoff return.

He also worked the Patriots vs. the Giants at the Meadowlands in the last game of the regular season, which New England won, 38-35. “The Giants didn’t have to play (hard with their playoff situation already decided),” says Carey. “But they did. The return game was big.” New York’s Domenik Hixson returned a kickoff 74 yards for a touchdown in that game.

This time Hixson returns the kick just 14 yards before being stopped cold by New England’s Raymond Ventrone.

“The Patriots just thumped them at the (17 yard) line,” says Carey. “Those are the things that take the steam out of somebody. It didn’t bode well for the Giants.”

New York is 83 yards from victory with 2:39 to play. Tough assignment against the New England defense. One remarkable play derails New England’s perfect season and makes this game one of the most exciting of all time.

With 1:15 remaining, Giants quarterback Eli Manning is facing a third-and-five from his own 44 yardline.

“I’m prepared for a hard count (with the Giants attempting to draw the Patriots off sides),” says Carey. But the ball is snapped. “The Giants protection breaks down immediately. I did something you’re not supposed to do. I’m on Eli’s right, his passing arm side. Everybody covers up Eli. I run around to his left side.”

Patriot defenders Jarvis Green and Richard Seymour get their hands on Manning, but can’t bring him down. Somehow Manning spins out of the tackles and fi res a deep pass. Some think the Patriots had Manning “in the grasp” before he let go of the ball.

“I got lucky to get a good look at it,” says Carey. “It was as close (to being in the grasp) as I’d like to have it. It just didn’t meet all the criteria. It wasn’t one where I hoped I was right.”

Carey is positive he is right not calling it a sack.

The Giants’ David Tyree makes a spectacular catch, clutching the ball against his helmet with one hand as he falls to the ground for a 32-yard gain. “I could tell from (back judge) Scott Helverson’s body motions something big had happened,” says Carey. “He said it was an unbelievable catch.”

Four plays later Manning connects with Plaxico Burress for a 13-yard touchdown that wins the game, 17-14.

Carey and his crew know immediately they have been part of something special.

“It was like we played the game,” he says. “It was euphoria. I don’t remember seeing anything to ask the officials to do diff erently. That’s very rare. Every year at the Super Bowl somebody asks me about that game. I didn’t make it memorable.”

Carey retired following the 2013 season after 24 years as an NFL official, the last 15 in the referee’s spot. He is 69, living in San Diego and still CEO of a company that manufactures snow sports equipment.

“I have some phenomenal memories,” he says. “I had a storybook career.”

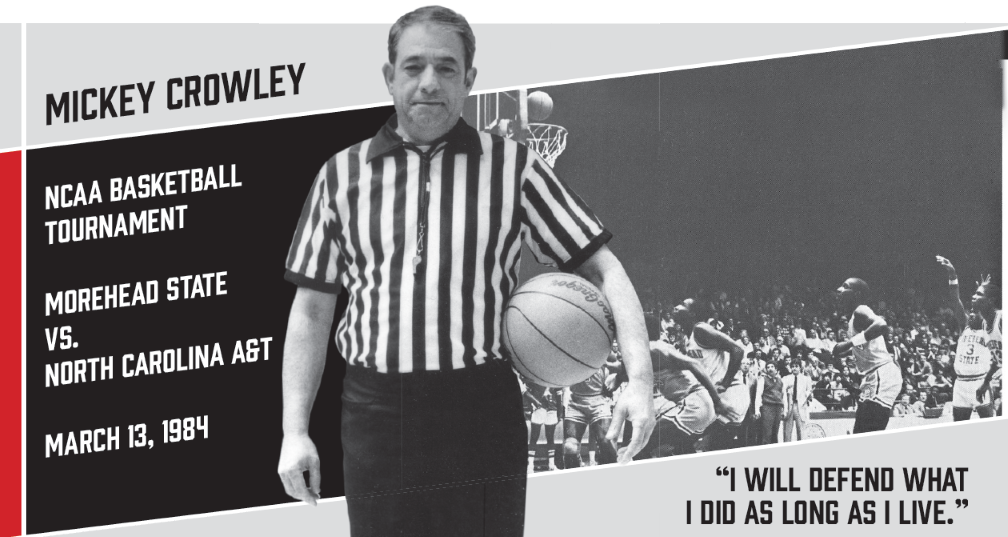

It is March 13, 1984, in the Dayton Arena. Morehead State and North Carolina A&T are meeting in a fi rst-round game of the NCAA Men’s Basketball Tournament. Tie game. Twenty-six seconds to play.

Mickey Crowley, one of the three referees on the All-Big East crew, calls a foul on a Morehead State player.

“I committed a cardinal sin for a referee.” says Crowley. “I turned my back (on the play) to make sure the clock stopped.”

Nowadays, referees often wear a belt pack that automatically stops the clock when they blow the whistle. But not in 1984.

No. 23, Eric Boyd, steps to line for A&T. The Aggies uniforms are yellow with white numerals, making the numbers tough to discern. Boyd is A&T’s second-leading scorer and a 66 percent foul shooter.

“Wayne Martin (the Morehead State coach) comes out and says, very politely, ‘Mickey, I think you’ve got the wrong shooter.’”

Crowley confers with his fellow officials. “I went to (Jim) Burr and say, ‘Do I have the right shooter?’ He says, ‘I’m not sure.’ I went to (Tim) Higgins and he says, ‘Don’t ask me.’”

Crowley goes to the alternate referee at the scorer’s table. He isn’t sure either. Next, he turns to the television announcers. He figures they can replay it.

“I ask the announcer and he says, ‘We should have it,’” says Crowley. “He looks at it.”

The announcer tells Crowley that No. 21, James Horace, should be the shooter. “I never looked at the TV monitor,” says Crowley.

Years later someone asks Crowley if he thinks the Aggies switched shooters on purpose. “No comment,” he replies.

Horace, a 51 percent foul shooter, goes to the line. “Nobody on the A&T bench complained,” says Crowley, confirming in his mind that the correct shooter is now at the line. Horace makes one of two free throws. The Aggies lead by one.

Morehead State’s Guy Minnifield makes a shot with four seconds left to give the Eagles a 70-69 victory.

Crowley creates a stir by using a television replay to help make the correct call. “You weren’t allowed to go to the TV (in those days),” he says. Crowley is unaware he is making a landmark decision that will change the way sports are officiated.

“When we got back to the hotel, the phone is jumping off the hook,” he says. “My wife calls and says you shouldn’t have done that. I ask her, ‘Did we get it right?’ She says, ‘Yes.’”

Technically, Crowley is not suspended. But he does not advance to the next round of the tournament. An NCAA spokesman claims the referee assignments are made before the tournament starts and Crowley is not scheduled to work any more games.

“I did take some heat,” says Crowley. “I got a lot of criticism.”

He works a full schedule of games in the 1984-85 season, plus the Big East tourney. He is not asked to work the NCAA Tournament that season. The following year Crowley is invited back to referee in the NCAAs.

“Imagine if I got it wrong,” says Crowley, now 84 and living in Calabash, N.C. “It would have been bigger news.”

In the last 20 years, most sports have adopted replay systems to determine close calls. “Now if you burp, they go to the TV monitor,” says Crowley with a laugh.

Crowley refereed NCAA Division I basketball games for 31 years. He worked his last game in 1991, when Duke beat Kansas to win the national championship. “I wanted to go out on top,” he says. He spends another 15 years as supervisor of officials for the Atlantic 10, Patriot League and Ivy League conferences.

But it is that 1984 Morehead State-North Carolina A&T game that will be remembered for changing how sports are officiated. “I will defend what I did as long as I live,” says Crowley. “We got it right!”

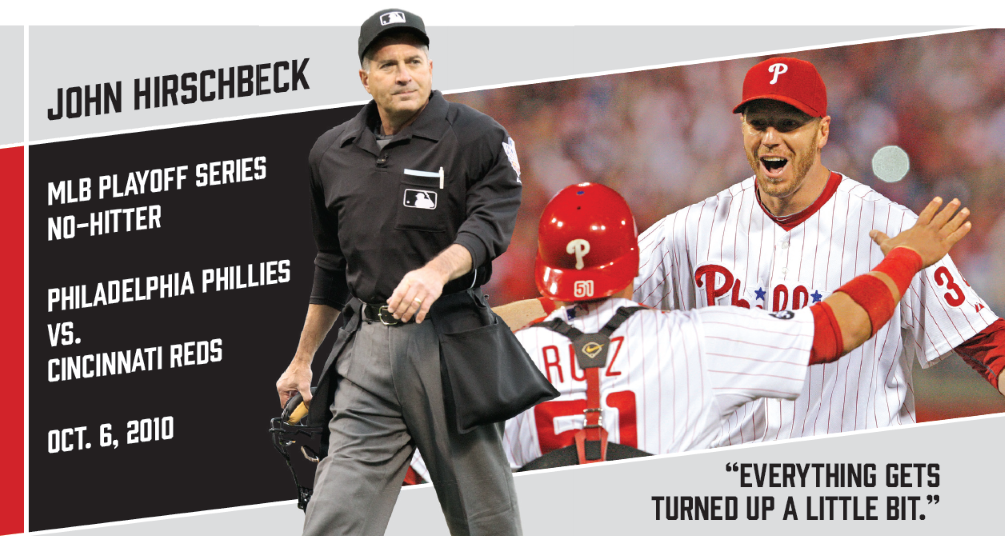

It is Oct. 6, 2010, at Citizens Bank Park in Philadelphia. The Phillies are facing the Cincinnati Reds in the first game of a best-of-five NL Division Series. Roy Halladay is pitching for Philadelphia and John Hirschbeck is umpiring home plate.

Hirschbeck can tell early in the game that Halladay has his best stuff. But he doesn’t realize that Halladay is pitching a no-hitter until he looks at the scoreboard after the fifth inning.

“Just keep doing what you’re doing,” Hirschbeck tells himself. “Don’t change anything. Don’t let it come down to anything you do.”

Hirschbeck, now 64 and still spending summers in North Lima, Ohio, says he doesn’t feel any extra pressure because of the possible no-hitter. He believes he is having a good game, too. “I was seeing the ball well,” he says.

The drama of a playoff provides all the pressure Hirschbeck needs to be sharp. “There’s a difference between a spring training game and a regular-season game, and a regular-season game and a playoff game,” he says. “Everything gets turned up a little bit. You try not to get amped up with the crowd.”

Halladay’s chance at a perfect game ends when Cincinnati’s Jay Bruce walks in the fifth inning on a 3-2 pitch. It is the Reds’ only baserunner of the game.

The Reds’ Brandon Phillips is the final batter in the ninth inning. He hits a tapper in front of the plate. Phillies catcher Carlos Ruiz fi elds the ball and throws out Phillips at first.

“I was prepared to call interference,” says Hirschbeck. “(Phillips) ran out of the 45-foot lane on the infield grass.” But Ruiz makes the play on Phillips. No need to make the interference call. The Phillies win, 4-0. The no-hitter is only the second in playoff history, joining the perfect game the Yankees’ Don Larsen threw in the 1956 World Series. Halladay throws 25 of 28 first-pitch strikes and 104 pitches total. The game is completed in a delightful two hours and 34 minutes.

There is more to this day for Hirschbeck than the no-hitter. He receives a call from his Cleveland Clinic doctor that morning before the game telling him that he has prostate cancer. He has already survived a bout with testicular cancer the year before when he has his right testicle removed.

“I couldn’t do anything about it (right away),” he says. “I tried to tell myself I’m not going to worry about it unless it’s something (serious). I will take care of it after the season.”

Hirschbeck’s son, Michael, 22 at the time, makes the trip with him to Philadelphia. He often travels with his father to games around the Northeast. When Michael is younger, he sometimes serves as a batboy for one of the teams.

The no-hitter is one of those special father-son days that neither will forget. Michael Hirschbeck passed away in 2014 from ALD, the second son that John lost to the disease.

After the game Hirschbeck asks the umpires’ clubhouse guy to get Halladay to autograph a picture from the game. Halladay does it willingly.

Halladay, who died in a plane crash in 2018, makes Hirschbeck’s job easy. “He threw strikes,” Hirschbeck said. “I was a pitcher’s umpire. I could call a ball, a strike. Never call a strike, a ball. I was consistent. I had the same strike zone all the time.”

It was the only time Hirschbeck worked home plate for a no-hitter. He was at first base when the Yankees’ David Wells threw a perfect game against Minnesota in 1998 and on the field for two of Nolan Ryan’s no-hitters.

Hirschbeck was also behind the plate when Barry Bonds hit his 756th career home run, surpassing Henry Aaron. He retired after working the 2016 World Series between the Chicago Cubs and Cleveland Indians, his third World Series and his 34th year in Major League Baseball.

“I was fortunate,” he says. “It’s fun when you look back.”

Gene Duffey is a sportswriter from Houston.

What's Your Call? Leave a Comment:

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.