Many umpires would agree that there are very few judgment calls in baseball that are tougher to make than a checked swing. Whether you are the plate umpire having to instantaneously switch your concentration from the pitch’s location to the hitter’s commitment, or a field umpire in the middle of the diamond with absolutely no angle, few situations can be tougher to judge.

The NCAA rulebook indicates that a checked swing shall be called a strike “if the barrel head of the bat crosses the front edge of home plate or the batter’s front hip.” That is pretty simple and straightforward language, however, not particularly easy to distinguish. The NFHS and pro rules don’t define a criterion for determining a checked swing. Umpires working under those sets of rules must simply determine if the batter committed to the swing or not.

A strike by definition is “a pitch that is struck at by the batter and is missed.” It’s up to the umpire’s judgment as to whether the batter “struck at” the pitch. Breaking the wrists or the bat moving beyond the front of the plate or the batter’s body are considerations that the umpire may use to make the judgment. They are simply considerations, not definitions.

Responsibility

Most umpires will agree that determining whether the batter swung at a pitch when he checks his swing is primarily the responsibility of the plate umpire. Plate umpires should try to get as many of those as they can without help. However, that can be a very difficult task on pitches that are on the fringes of the strike zone. Those pitches require intense concentration on the pitch’s relationship to the strike zone. Consequently, letting your eyes stray to the batter when he checks his swing may not be possible. However, on pitches that you can tell are going to be out of the strike zone, it is wise to allow yourself the freedom to change your focus from the ball to the batter as he starts his swing.

Determining if the batter went

When you determine that the hitter has indeed committed, letting everyone know in an assertive manner that you have a swing can avoid problems. A good technique is pointing at the batter with your left index finger and discernibly making the strike sign with your right hand, while making a verbal call such as, “Yes, he went!” or “That’s a swing!” I believe that less controversy will follow from the plate umpire making that call himself on a very questionable checked swing, than if he has to go to one of his partners for help in the same situation.

Who to ask

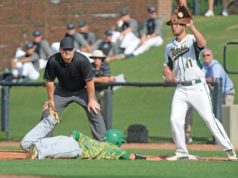

Even though we might all agree that it’s best for the plate umpire to get as many checked swings as possible, the reality is that you will have to appeal to a partner occasionally. It’s accepted practice at all levels of baseball to get help when the pitcher, catcher or head coach ask. In two-umpire mechanics, the base umpire has to give his best perspective regardless if he is on the line with no runners on, or in the middle with runners on base. That is an easier call to make on the first-base line. In three-umpire mechanics, the proper technique is to go to the base umpire who is on the open side of the batter even if that umpire has moved to the infield due to combinations of runners on base.

Appeal is made

When an appeal is made, the base umpire will make an emphatic strike sign or the safe signal if the batter didn’t go. As in all situations, how much you need to sell the call with voice and signal will be determined by how critical the situation is in the game. Base umpires need to always be ready to help with a ruling on a checked swing by watching the batter closely. The only person to whom a base umpire can respond on a request for appeal of a checked swing is the plate umpire, and only when the plate umpire has ruled the pitch a ball.

We’ve all seen a catcher point down to a base umpire on a checked swing asking for an appeal. When that happens, the base umpire should simply ignore the appeal until he sees a request from the plate umpire. Imagine the embarrassment if a catcher pointed down asking for an appeal not knowing that the plate umpire had ruled a pitch a swinging strike, and the base umpire ruled no swing.

Granting the appeal

Umpires need to accept that asking for help is the right thing to do when an appeal is requested, even if they are sure that the batter didn’t commit. At one point in my career I would emphatically voice, “No, he didn’t go” on checked swings when I was sure the batter didn’t swing. I thought it was a good way to let the catcher and others in earshot know that I was in command of the situation. I no longer advocate that approach, since you are obliged to get help when asked. Careful communication with your catcher can help prevent too many checked swing appeals during a game.

As a plate umpire, when I appeal for help from one of my partners on a checked swing, I will repeat what my partner rules and then flash the count on the batter as a result of that ruling. That communicates to everyone that our crew is working as a team to get calls right. It also can avoid confusion on my part or on the part of the scoreboard operator as to the correct ball-strike count, if my original call is overturned. The crew in its pregame meeting should discuss checked swings. I always let my partners know prior to a game that when I come to them for help, I want them to rule the way they saw the play, regardless if they uphold or overrule my call. Protecting your partner’s feelings should not enter into making the call.

There are some instances when the plate umpire will not want to wait for an appeal from the defensive team on a checked swing. One of those situations involves a checked swing on a two-strike pitch with two outs and runner(s) on base. If they are attempting to steal on the pitch, the catcher’s throw to one of the bases could cause problems for the crew. You might have an overthrow into the outfield, a very close play at the base or perhaps a rundown situation. Each of those scenarios will require plays from players and calls from umpires that may be unnecessary if the batter didn’t check his swing in time.

What's Your Call? Leave a Comment:

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.