By Dan Ronan

A late May MLB game between the New York Mets and the St. Louis Cardinals pointed out the challenges ESPN, Fox and the regional sports networks have when it comes to projecting their image of the umpire’s three-dimensional strike zone on a flat television screen. Plate umpire Gabe Morales called pitcher Miles Mikolas’ 3-2 sinker ball four.

The St. Louis broadcast onscreen graphic showed it as a ball. However, if you were watching the New York Mets feed it showed the pitch as a strike. The same pitch, two different results on TV.

“The image on TV is not accurate,” retired MLB umpire/crew chief Dale Scott said during an interview with Referee in Baltimore. “In this case something was not right. I do not know where they are getting the data and how they are setting it up. And there is no way they are accurate on the high and low pitches.”

That disparity and the recent addition of websites, such as umpscorecards.com — which tracks every MLB game and then assigns its score to an umpire’s performance on balls and strikes, but without the benefit of training or umpiring experience — is adding to the controversy.

“The umpiring at the MLB level is probably better than it has ever been,” retired MLB Vice President of Umpiring Mike Port told Referee. “Yes, someone is going to have a bad game and it makes it into the media and onto social media. It happens. But I have seen players swing and miss, drop fly balls and make baserunning mistakes more frequently than umpires miss pitches or calls. But now it is all on social media; it is what people perceive.”

“I am so glad I was not on social media when I was on the field working. It is just brutal out there,” remarked Scott. “People see these scores posted every day on social media and they say this guy sucks.”

And it is that perception Port and Scott believe is unduly raising questions about the judgment, expertise and credibility of highly trained MLB umpires, when it seems that anyone who has ever sat in the Bob Uecker cheap seats and has a Twitter account believes they can call balls and strikes better than an MLB umpire, who, on average had nine years of experience in the minor leagues before joining the MLB staff.

“Before someone is promoted to the Major League staff they will put in a long apprenticeship, nine or 10 years,” Port said. “That is equivalent to what it takes to become a neurosurgeon. Major League Baseball is in a newfound search for perfection, when in fact they should be pursuing excellence. You weave into that the old storyline that umpires are bad, we have to ‘fix’ the umpires.”

The best place to start when discussing the professional baseball strike zone is the official MLB rulebook.

“The official strike zone is the area over home plate from the midpoint between a batter’s shoulders and the top of the uniform pants — when the batter is in his stance and prepared to swing at a pitched ball — and a point just below the kneecap,” the rulebook states. In order to get a strike call, “part of the ball must cross over part of home plate while in the aforementioned area.”

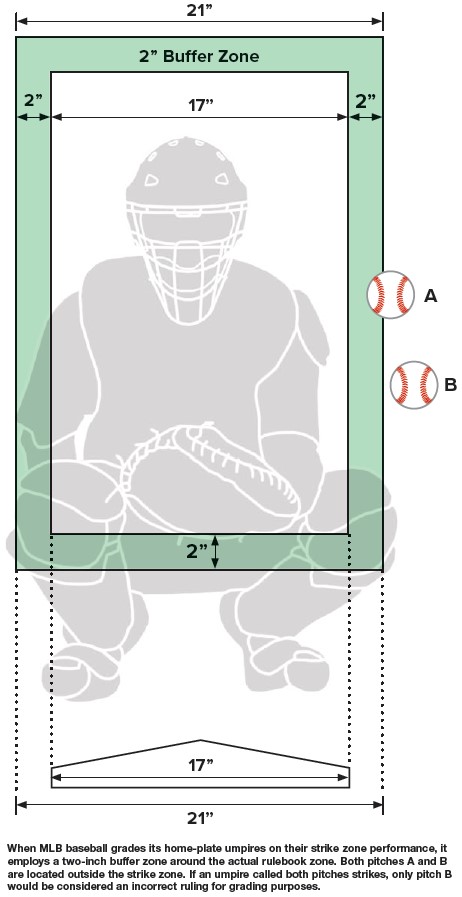

The five-sided home plate is 17 inches wide, and the 2.86-to-2.94-inch diameter Rawlings baseball needs only to pass over any part of the plate in the strike zone to be called a strike.

Sounds simple, doesn’t it?

But the strike zone is not an end zone spray painted on a wall of a school building. It is an idea or concept with a rulebook definition that has been modified countless times over the years. Port, Scott and others say because of better training and video systems that did not exist years ago, the strike zone is much more uniform now than it was a generation ago when old-school umpires believed almost every pitch had the potential to be a strike. Veteran 1980s and ‘90s NL arbiters such as Lee Weyer, Frank Pulli and Eric Gregg were known for their exceptionally wide, but lower, strike zones, while others, especially in the AL, had reputations for strike zones resembling a shoe box, narrow on the corners and much more vertical.

Umpires must also consider the diversity in the size of MLB players from the giants like 6-foot-7 Yankees outfielder Aaron Judge to Houston’s 5-6 second baseman José Altuve. Some batters stand upright. Others are crouched. Some are as close as possible to the plate. Some are a bit farther away and umpires are being asked to make split-second decisions on 100-mph pitches with diabolical movement and spin not seen in prior generations.

The day after an MLB umpire works the plate, he logs onto the MLB Zone Evaluator system that tracks every pitch and notes every pitch called correctly, the ones labeled incorrect and then assigns a percentage score to the game. Port, Scott and other sources say MLB’s ZE system also considers a two-inch buffer zone on the corners of the plate to take into account the width of the baseball and the fact that a pitch that “nicks” the corner and is not fully on the plate should be called a strike. So, the strike zone can be at least 21 inches wide.

“If I work the plate on a Thursday night, I get my evaluation the next day on a Friday and a technician and a supervisor will have reviewed the data manually,” Scott explained.

Over the last 20 years MLB has been through several video evaluation systems for its umpires. The league says each one is better than the one it is replacing. ESPN first began using its K-zone system back in 2001.

Unlike the boxes or 3-D graphics seen on TV, an MLB employee resets the strike zone for each batter and after the game evaluates the borderline pitches before submitting the final score to an umpire supervisor for review and then to the home-plate umpire. Scott says during a regular game it is not uncommon to have five to eight pitches reviewed by the staff because they were so close and it is typical that half of them will be ruled in favor of the umpire, increasing his correct call percentage one or two points and raising his overall game average.

The umpire’s union also created a Zone Enforcement committee to double-check calls it believes are incorrect and file appeals to have the scoring of pitches reviewed.

The umpire’s union also created a Zone Enforcement committee to double-check calls it believes are incorrect and file appeals to have the scoring of pitches reviewed.

In 2021, roughly 30 percent of the pitches appealed, including those in which a pitcher either misses his spot and the ball ends up in the strike zone or the catcher mishandles the pitch and it crosses the plate, were overturned.

The 2022 season was just weeks old when the first umpiring controversy erupted during the April 25 nationally televised ESPN Sunday Night Baseball game. Umpire Angel Hernandez ejected the Philadelphia Phillies’ Kyle Schwarber after a close pitch was called strike three. Twitter and the announcers in the booth had a collective meltdown.

After the game, video showed numerous angry fans were waiting for Hernandez’s vehicle, hurling insults at him as he left Citizens Bank Park.

The next day Umpscorecards.com offered its take on Hernandez’s performance, claiming the veteran umpire scored an 88 percent accuracy rate. Another partisan site, Phillienation.com, cited a second source, @umpireauditor, and said Hernandez missed a staggering 19 pitches and scored an abysmal 85.3 percent. Wrong.

While MLB does not publicly release an umpire’s plate scores, the next day retired umpire Joe West just happened to be a guest on Chicago sports radio station WSCR-AM, the Cubs’ flagship station. West gave the hosts some insight into MLB’s ZE system, and he said Hernandez had scored a very solid, much higher 96.12 percent accuracy rate.

“They need to sync the strike zone that they’re grading him in public media to the strike zone they’re grading him in baseball,” West said on WSCR. “I called Angel and talked with him, and the office said he scored a 96 and the media are saying he scored an 85. You cannot have two different strike zones. If they are all the same, I have no problem, but if the discrepancy is between 85 percent and 96 percent, I have a real problem with that. He is getting a raw deal here.”

John Kramer of Atlanta knows quite a bit about umpiring and broadcasting. Kramer is a former minor league umpire. He’s also a retired college baseball umpire who worked as a crew chief in the SEC and ACC, including during an ACC tournament. He worked five NCAA Regionals and one Super Regional. For the past 45 years he has been a fixture at Atlanta Fulton County Stadium, Turner Field and Truist Park as the Braves’ public address announcer, a radio engineer/producer for visiting MLB teams and working in the stadium’s television control room. He has observed the ESPN K-zone and video strike zone on the regional sports networks, and he says the strike zone you see on TV or on social media is not the one on the field.

“In Atlanta, we had an IT programmer who came to me and said, ‘Can you depict what the strike zone would be, if I put it on the screen?’” Kramer said. “He read the rulebook and had the strike zone all the way up to his chest and way too low. I kept working with him to get it closer and closer. But if you do not have someone with umpiring experience, standing over his shoulder helping him set it up, it will not be right. At ESPN and the regional sports networks there is a graphic artist, and each creates a different version of the strike zone. Each network has a different version. There is no standardization and until there is, it is useless.”

But while Kramer says the different versions of the strike zone are useless, each day an estimated 250,000 Twitter followers of UmpireScorecards.com anxiously await the previous day’s games and the site’s review of the 15 umpires who are calling balls and strikes each night.

The Twitter account and website were co-founded by Boston University computer science and statistics major Ethan Singer and Penn State University undergraduate Ethan Schwartz. Singer says their website uses a wide variety of calculations, including Monte Carlo algorithms and collision geometry to create what he says is “interpretability, validity, practicality and fairness” to determine a call’s accuracy. UmpScorecards uses data from MLB’s game tracking program Statcast that is available in real time at MLB.com.

“We report the data to the best of our ability,” Singer told Referee. “There is some extra leniency. We want to make sure no one gets penalized for incorrect data. But we did not add a plain buffer zone, as MLB has done. I think we do fill a void and the combination of posting on Twitter and our graphics have been the key to our success.”

Singer says his website has been modified numerous times to try to make it fairer to the MLB umpires and there is less reliance on raw data to determine if a pitch is called correctly or incorrectly.

Singer admits that being an MLB umpire and calling balls and strikes is one of the toughest jobs in sports.

“A baseball is moving at close to 100 miles per hour with unbelievable movement and your view is restricted and it is kind of an inhuman task,” Singer said. “One of things we have enjoyed the most is highlighting and showcasing to people how good umpires are. I do acknowledge how difficult a job they have.”

Earlier in the season on Umpscorecards.com, the median umpire rendered a correct call on 93.5 percent of pitches. Eight umpires were averaging at least 95 percent accuracy and 94 percent consistency.

Southern California’s Lindsey Imber is the founder of Closecallsports.com, a website devoted to MLB rule interpretations, coverage of ejections and other umpiring issues. She says technology is significantly improving MLB umpiring; however, she is worried that many of those so-called hobbyists who have created the umpiring websites and the media members who promote them as 100 percent accurate do not understand the game’s nuances and the difficulty of umpiring in today’s social-media-saturated society.

“We think computers are infallible because that’s what we’ve been taught to believe,” Imber said. “Therefore, we expect human umpires to be perfect because if the computers can judge balls and strikes, then humans should be able to do it. And if the computer is that good, you sense where this is going with the whole robo-umpire argument.”

Imber believes MLB’s 2013-14 decision to add video review to fair/foul, safe/out and some other calls means the old-school, manager-to-umpire argument after a close play at second base is gone forever and the only thing left to argue about is the occasional weird play and now balls and strikes.

“The media lost its ability to highlight arguments on regular plays because of instant replay. They get fixed by New York. So now everything is highly concentrated on balls and strikes, check swings and non-renewable plays,” she insisted.

Since MLB does not make its individual umpiring data available and considers that information to be akin to an employee’s confidential job evaluation, it is unclear if its scores are higher or lower than those being published by the various social media websites. However, based on the interview West did with the Chicago radio station, it can be surmised the MLB scores are higher.

According to ESPN, MLB breaks down pitches into three categories: “correct” calls, “acceptable” calls within the so-called buffer zone and “incorrect” calls. In 2021 by MLB’s calculations, the umpires on correct and acceptable calls were 97.4 percent, measuring the plate 21 inches wide, which includes the 17-inch plate and the two-inch buffer zone. The highest-rated umpire graded out at 98.5 percent and the lowest at 96 percent.

“We don’t know how accurate these on-screen strike zones are, but they have become reality to baseball fans,” Scott said.

After spending an entire career in baseball as a player, team executive and MLB executive, Port realizes there is an information vacuum, and the media and fans want more information about the quality of the job umpires are doing. But he believes the hobbyists who have created these websites and manage them daily are doing the game and umpires a long-term disservice.

“Major League Baseball, given the resources it has both financially and timewise, has gone to great lengths to develop the very best systems they possibly can,” Port said. “Now some fellow sitting in his basement charting pitches eating day old hot dogs, I doubt he is qualified to evaluate balls and strikes watching a game on TV. On TV you have no appreciation for depth perception and often the camera angles are different.”

Port also blames the television networks and media for creating a controversy and stoking the fires.

“Certainly, the media is an eternal aggravation to me when they talk about a pitch or a play,” he said emphatically. “Ninety-nine times out of 100 they will say he apparently, he missed the pitch, but they have the benefit of endless replays and endless time. Make a decision and call it and drop the ‘apparently.’ The umpire on the field must decide in an instant.”

Dan Ronan is the associate editor and business reporter at Transport Topics, ttnews.com, and he is an anchor on SiriusXM satellite radio.

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.