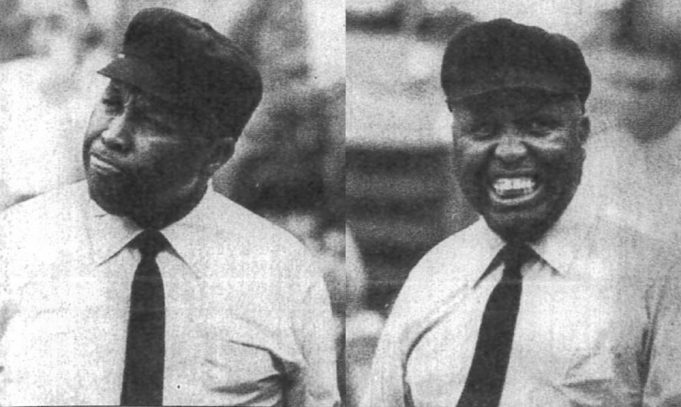

From the minors to the majors, Emmett Ashford was an umpire who had style. His career was typified by an incident in his first American League (A.L.) game behind the plate and his fourth big league game overall. In the sixth inning of a tie game in Baltimore, Orioles’ catcher Andy Etchebarren went into the stands for a foul ball knowing he could not reach it but hoping a fan might put the ball into the catcher’s glove. Etchebarren later told the media, “I looked up and there was Emmett in the stands with me.”

That dramatic flair made Ashford a crowd favorite; it also brought charges that his antics interfered with his umpiring. Several of his crew chiefs agreed that the qualities sending Ashford to the A.L. – his personality and animation – were the same ones that kept him from being a good umpire. “You can’t do two things at once,” said Jim Honochick, a retired A.L. – umpire and ex-crew chief. “You can’t be a good showman and a good umpire.”

Others disagree. Some feel Ashford was both competent and brought spirit and enthusiasm to the game in the mid-1960’s, when those qualities were in short supply in the majors. Eddie Stanky, former major league player and an ex-manager, said that Ashford “could umpire in the major leagues today.”

Ashford’s five-year A.L. career was heavily covered by the media, spawning a number of oft-repeated stories:

- On opening day of the 1966 season, Ashford was in Washington for his first big league game. The problem: The guards at the gate were reluctant to allow a black man to enter the umpires’ dressing room.

- Ashford had a ritual of leaving the pregame meeting at home plate by dashing to his position, either broad jumping the pitcher’s mound on his way to second base or running all the way down the foul line before returning to his station at first or third base.

- He had a penchant for running full tilt into the outfield to watch the fielder catch a fly ball.

- And, of course, there was Ashford’s pirouette as he called out a runner.

There were also stories about Ashford’s fabled cufflinks, his wardrobe and his choice of restaurants. As ex-A.L. crew

chief Hank Soar recalled about Ashford: “He was very proud of his clothes and fastidious about the way he looked. After a long doubleheader, the rest of (the umps) would throw our stuff in trunks, knowing it would be cleaned and pressed at the next park. But he would carefully fold everything and put it in its proper place.”

Soar also remembered how Ashford introduced his crewmates to some of the better restaurants on the West coast. Said Soar: “Everybody knew Emmett. One Sunday night in L.A., we went out for a late supper. When we got to the place it was packed. I said, ‘We’ll never get out of here in time to make our plane.’ As we got in line, Emmett talked to the maître d’, who soon came over and said, ‘Mr. Ashford, your table is ready.’ (Emmett) was a great guy and I really enjoyed having him with me.”

RACIAL MATTERS.

Ashford’s personality also helped make him a pioneer. He claimed to have been the first black student-body president at his high school, the first black editor of the school newspaper and the first black cashier at a local market that previously hired blacks only as janitors and stockers. He was definitely the first black major league umpire, to be followed by Art Williams, the National League’s first black umpire, and then by the N.L.’s Eric Gregg and Charlie Williams, and part-time A.L. ump Chuck Meriwether.

Black players had already eased the way for Ashford, who publicly downplayed racial problems declaring that “even though players have been boiling over, there’s never been a racial slur.” Ashford also said that he had received only two negative letters: One from a little girl who was displeased with an Ashford decision; another, written on toilet paper, from a correspondent in Louisiana.

Given the social and racial turmoil of the times (mid-1960’s), however, it seems likely that the truth was considerably more harsh. Bill Valentine, who spent two years with Ashford in the Pacific Coast League (PCL) and another year with him on the same A.L. crew, provided more insight. “Emmett started out as a black umpire when there weren’t any black umpires,” said Valentine. “He worked in places such as the Arizona-Texas League, where his partners probably didn’t even speak to him, probably stayed in different rooms and just showed up to work the games. They probably tried to bury him because he was a black ump in a Class C league …. And when he got to the PCL, some of the older umps and Emmett had no use for each other.”

The lower minors were admittedly a problem. Ashford talked about his first tryout, in Mexicali of the Class C Southwest International League, when his umpiring partner failed to show. Ashford had to get a semi pro ump from El Centro to work the bases while Emmett worked behind the plate … for all four games over the July 4 weekend.

Caesar “Cece” Carlucci, who for 922 games was Ashford’s PCL crew chief, conceded that initially there was some

negative feeling in 1954, when Ashford rose to the PCL. “That was my year as a crew chief and I was looking forward to our regular preseason meeting, but it was canceled,” said Carlucci, “I think because they were bringing up a black guy and some of the old-timers didn’t like it.”

While racial incidents were not an every-day affair, Carlucci was involved in one that reached near-legend status. Recalled Carlucci : “At a game in Portland, one manager, who had argued with Emmett the night before and was convinced the call cost him the game, came out and handed Emmett the lineup card and said: ‘It’s not you I’m mad at, Emmett; it’s those two other guys.’ I was the crew chief and I went right over and said, ‘What are you talking about?’ And he said, ‘Not you, those other two.’ So I repeated, ‘Who the hell are the other two?’ And he replied, ‘Abe Lincoln for freeing them and Branch Rickey for bringing them into baseball.’

Carlucci also remembered that the crew traveled together and stayed in the same hotels, even though in Salt Lake City they had to change hotels because the restaurant wouldn’t serve Ashford. Later in his career, Emmett went his own way more and more as he developed his circle of friends and as black groups asked him to functions to be honored for being the first black big league ump.

TOO MUCH SHOW.

It would be easier to ascribe to racism Ashford’s baseball difficulties if his personality hadn’t been a major factor. The antipathy fellow umps showed toward Ashford may have had little to do with his race. Many of the more senior umps simply disapproved of Emmett’s “act.” No matter how many different words were used to describe Ashford, it always boiled down to him being a “showboat.” The umps were too conservative to accept Ashford’s act because they felt it detracted from the dignity of the profession and that he sacrificed accuracy for drawing the spotlight.

Several of Ashford’s A.L. crewmates recalled that he actually had more problems with black players than with others. “They just wanted him to do the job,” said John Rice. Concurred Valentine: “Some of the whites would back away, while the blacks would tell him: ‘Cut out the show and umpire, man. Get it right.’ ”

There were rumors that Joe Cronin, A.L. president, had let it be known that he wanted managers and players to go easy on Ashford. Not so, said Sam Mele, Twins’ manager when Emmett came up, and Bill Rigney, Angels’ manager at the time. Mele insisted: “I was never to do anything like that. And if I were, I’d have ignored it.. .. ” Rigney merely said: “I never heard any such thing in the 18 years I managed. If somebody thought (Emmett) made a bad call, they didn’t get on him because he was black; it was because he was an umpire.”

While Ashford spent 15 years in the minors, that tenure wasn’t rare and wasn’t necessarily related to his race. There were other umps who spent longer times in the bush leagues without ever getting shots at the show. Even some of those who rose to the big leagues spent long tours in the minors. (For example, Dutch Rennert worked in the bushes for 16 years before joining the N.L.)

After umpiring in the minors for two full seasons, in 1954 Ashford joined the PCL, which was a far different league then. Today, the PCL is Triple A; in 1954, it was an open-classification league proudly referred to on the West Coast as the “third major league.” Among the PCL players were ex-big leaguers or aspiring major leaguers who at times were better paid than some of those in the majors.

Valentine said that he and some players took pay cuts to move up to the majors. Besides, Ashford had grown up and gone to college in the Los Angeles area, so he was near home and in front of fans who for years had seen him work amateur football, basketball and baseball. All things considered, Emmett didn’t fare too badly.

But Ashford had gotten a late start on his life’s work. Officially, he was 36 when he began in pro baseball, 51 when he hit the A.L. in 1966. However, those who worked with him are convinced that Ashford’s “baseball age” was less than his real age. “He really and truly had a few years on most of us,” said John Rice, ex A.L. crew chief.

To some degree, that may have meant Ashford’s umpiring skills had diminished, but he was still athletic, boasting when he was 50 that he could still do public exhibit ions of high board diving. He also told Hank Soar that while younger,

Ashford had trained with Jesse Owens on the L.A. playgrounds. Soar called Ashford “one of the finest runners I ever saw. He was small (5’7″, 190 pounds), but at Fenway he could beat the ball to the outfield. The problem was that he’d lose sight of it and have to look back to the infield to get a sign from us.”

From the umpire’s perspective, that was the essence of Ashford’s problem: He sacrificed substance and accuracy for style. He’d run straight out to the outfield, rather than getting a good angle, to see the ball being caught. Or he’d get too close to plays at first base and get blocked out. Or, as Rice said, “He’d go into a call a little ahead of time and get into his big windup and, glory be, the guy would beat the play and (Emmett) would blow it.”

Carlucci talked about the same problem. “He’d wind up and flip-flop. It was unbelievable. That’s on a wide-open play, say the ball was foul and everybody in the world knew it – go ahead and stand on your head. But if you’ve got a ball down the line and it’s doubtful and you’re turning too quick so you can put on a show, that’s when it hits the fan.”

That’s just what happened one time in San Diego. Related Carlucci: “There was a bunted ball down the first-base line. I was at first and saw the first baseman hit the ball and chalk, but Emmett was behind the plate and had turned to go into a big motion. His back was to the play. So I was pointing fair and he was pointing foul. His show got him in trouble, but the fans didn’t think so.”

A FAN’S UMP, NOT AN UMP’S UMP.

Indeed. Ashford was so popular with the fans that his photograph was on PCL programs when he came to town. “The hometown fans would boo their manager if he came out to argue with Emmett,” said Carlucci. “He won them over, but he was a fan’s ump, not an ump’s ump.”

Carlucci said he tried to break Ashford of his theatrics and so did major league crew chiefs. Soar said he “had more trouble with him in two or three weeks than I had in 20 years in the league. I found out late in the second year why I had so much trouble when Emmett complained that nobody was watching him.”

Others, however, supported Ashford, whom Sam Mele compared with Pete Rose, saying: “Emmett was always hustling, always on top of the play. And he had showmanship – he wasn’t showing off – and we needed that in the game.” Bill Rigney echoed that observation: ” I thought he was a better-than-average umpire. He was always hustling, on top of everything. He was beautiful on balls and strikes. He didn’t carry over any bad feeling and he had a marvelous way of calling you out. It was refreshing to see his (crew) when they came into town.”

Even Eddie Stanky, the man the Boston Globe once called one of “baseball ‘s well-known umpire baiters,” then managing the White Sox, said Ashford “had ability as an umpire, plus showmanship …. His sense of humor and personality never interfered with his fine work behind the plate or on the bases.”

It was also said that Ashford was easy to talk to and that he was fair. Mele described a typical situation: “He was an average umpire, but he worked hard and if he made a mistake he told you. One time I went out to discuss a play with him and he called over John Stevens (crew chief) and said, ‘How’d you see it?’ Stevens said, ‘Emmett, I hate to say it but Sam’s right.’ And Emmett said, ‘Okay, I’m wrong’ and changed his decision.”

Ashford wasn’t averse to asking for help or reversing his original calls. He did it when he miscalled trapped fly balls, foul balls, ground-rule doubles. He’d confer with his crewmates and get it right even if that meant changing a call. “Most managers just want to get it right,” said Rigney. ” I’ve won games on umpires’ calls I knew were wrong and winning by a misinterpretation didn’t taste right.”

END OF THE LINE.

Ashford’s major league umpiring career concluded with the 1970 World Series, an event he termed “the culmination of my dreams.” He had already overstayed by a year the A.L. maximum age in order to qualify for a pension. He left saying: “I have done something I wanted to do. I have that satisfaction.”

For the next 10 years, Ashford was commissioner Bowie Kuhn’s West Coast representative and Emmett also continued to umpire college and other amateur baseball and basketball games.

Even after he died, Ashford continued to be a pioneer of sorts. Shortly after he suffered a fatal heart attack on March 1, 1980, his widow Virginia contacted the Baseball Hall of Fame. Recalled Howard Talbot, director of the museum at Copperstown: “Soon afterward, his ashes arrived in a brass urn, but we hadn’t made any provisions for such an event. We briefly thought about creating an area within the museum, perhaps in a wall, but discard that in favor of buying several plots overlooking Otsego Lake in a cemetery about half a mile from the museum.”

A retired Episcopal minister, who had once been a batboy in Ebbetts Field visiting clubhouse, conducted the service with a handful of people from the Hall in attendance. Emmett is still the only baseball personality buried in that cemetery. “And every year,” said Talbot, “his wife makes sure there are flowers on his grave for Memorial Day.”

The music at Ashford’s memorial service in L.A. included the song My Way. It was appropriate because that’s how he lived. He enjoyed style in life, liked to go first class. And it carried over into his need for his own style of baseball. “He took a lot of pride in being where he was and who he was.” Said Bill Rigney. “I think he just wanted to establish his own identity so people would remember Emmett Ashford the umpire, not Emmett Ashford the black umpire.”

Truly, Emmett Ashford was one of a kind. And his legacy seems intact. Long since his last major league game, people still talk about Emmett Ashford.

This article was published in Referee Magazine on September 1992.

This article was published in Referee Magazine on September 1992.

What's Your Call? Leave a Comment:

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.