Thornton Jenkins had so much more than an NCAA basketball championship game to officiate when Texas Western tipped off against the University of Kentucky in College Park, Md., on March 19, 1966. He had a watershed moment in American race relations to witness.

As he approached that moment, what was he thinking?

Nothing different from any other game, said Jenkins, who worked the game with the late Steve Honzo.

His main concern? “We just made sure that, when they got fouled shooting, they got two shots,” Jenkins said.

“The color barrier, in those days, just wasn’t a factor. It was just one of those things, and that was it. I never heard the word ‘race’ mentioned during the game,” he added, pointing out that the gym was dominated by Kentucky fans. Indeed, in the preview of the 1966 Final Four for Sports Illustrated, Frank Deford noted that Texas Western’s black-dominated roster was “hardly a startling fact nowadays.” However, he also noted that some in the nation were “referring to the prospective national final as not just a game, but as a contest for racial honors.”

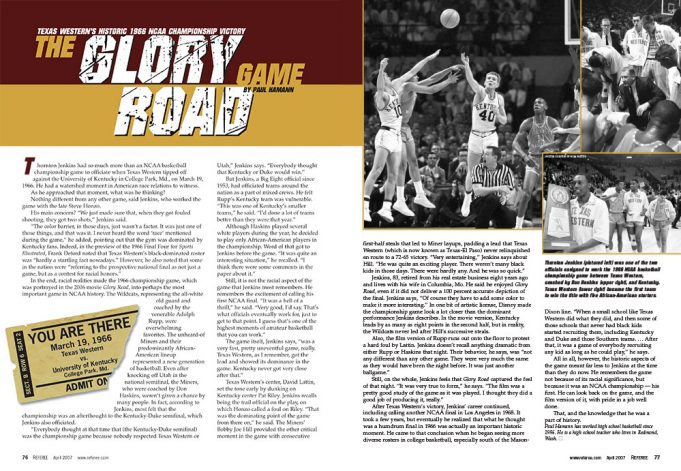

In the end, racial realities made the 1966 championship game, which was portrayed in the 2006 movie Glory Road, into perhaps the most important game in NCAA history. The Wildcats, representing the all-whiteold guard and coached by the venerable Adolph Rupp, were overwhelming favorites. The unheard-of Miners and their predominantly African- American lineup represented a new generation of basketball. Even after knocking off Utah in the national semifinal, the Miners, who were coached by Don Haskins, weren’t given a chance by many people. In fact, according to Jenkins, most felt that the championship was an afterthought to the Kentucky-Duke semifinal, which Jenkins also officiated.

“Everybody thought at that time that (the Kentucky-Duke semifinal) was the championship game because nobody respected Texas Western or Utah,” Jenkins says. “Everybody thought that Kentucky or Duke would win.”

But Jenkins, a Big Eight official since 1953, had officiated teams around the nation as a part of mixed crews. He felt Rupp’s Kentucky team was vulnerable. “This was one of Kentucky’s smaller teams,” he said. “I’d done a lot of teams better than they were that year.”

Although Haskins played several white players during the year, he decided to play only African-American players in the championship. Word of that got to Jenkins before the game. “It was quite an interesting situation,” he recalled. “I think there were some comments in the paper about it.”

Still, it is not the racial aspect of the game that Jenkins most remembers. He remembers the excitement of calling his first NCAA final. “It was a hell of a thrill,” he said. “Very good, I’d say. That’s what officials eventually work for, just to get to that point. I guess that’s one of the highest moments of amateur basketball that you can work.”

The game itself, Jenkins says, “was a very fast, pretty uneventful game, really. Texas Western, as I remember, got the lead and showed its dominance in the game. Kentucky never got very close after that.”

Texas Western’s center, David Lattin, set the tone early by dunking on Kentucky center Pat Riley. Jenkins recalls being the trail official on the play, on which Honzo called a foul on Riley. “That was the dominating point of the game from there on,” he said. The Miners’ Bobby Joe Hill provided the other critical moment in the game with consecutive first-half steals that led to Miner layups, padding a lead that Texas Western (which is now known as Texas-El Paso) never relinquished en route to a 72-65 victory. “Very entertaining,” Jenkins says about Hill. “He was quite an exciting player. There weren’t many black kids in those days. There were hardly any. And he was so quick.”

Jenkins, 83, retired from his real estate business eight years ago and lives with his wife in Columbia, Mo. He said he enjoyed Glory Road, even if it did not deliver a 100 percent accurate depiction of the final. Jenkins says, “Of course they have to add some color to make it more interesting.” In one bit of artistic license, Disney made the championship game look a lot closer than the dominant performance Jenkins describes. In the movie version, Kentucky leads by as many as eight points in the second half, but in reality, the Wildcats never led after Hill’s successive steals.

Also, the film version of Rupp runs out onto the floor to protest a hard foul by Lattin. Jenkins doesn’t recall anything dramatic from either Rupp or Haskins that night. Their behavior, he says, was “not any different than any other game. They were very much the same as they would have been the night before. It was just another ballgame.”

Still, on the whole, Jenkins feels that Glory Road captured the feel of that night. “It was very true to form,” he says. “The film was a pretty good study of the game as it was played. I thought they did a good job of producing it, really.”

After Texas Western’s victory, Jenkins’ career continued, including calling another NCAA final in Los Angeles in 1968. It took a few years, but eventually he realized that what he thought was a humdrum final in 1966 was actually an important historic moment. He came to that conclusion when he began seeing more diverse rosters in college basketball, especially south of the Mason-Dixon line. “When a small school like Texas Western did what they did, and then some of those schools that never had black kids started recruiting them, including Kentucky and Duke and those Southern teams. … After that, it was a game of everybody recruiting any kid as long as he could play,” he says.

All in all, however, the historic aspects of the game meant far less to Jenkins at the time than they do now. He remembers the game not because of its racial significance, but because it was an NCAA championship — his first. He can look back on the game, and the film version of it, with pride in a job well done.

That, and the knowledge that he was a part of history.

Paul Hamann has worked high school basketball since 1996. He is a high school teacher who lives in Redmond, Wash.

What's Your Call? Leave a Comment:

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.