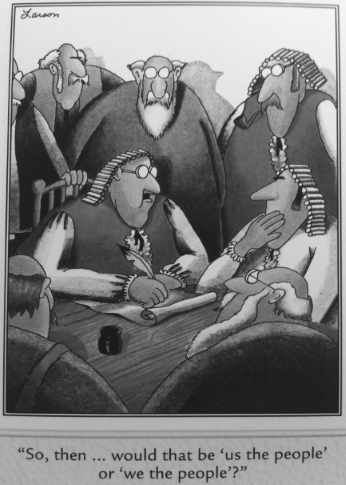

When I think about the process of writing rules, I remember a “The Far Side” cartoon in which some solemn-looking American colonists were gathered around another who was seated at a desk. Quill pen poised, he looked thoughtfully at a blank piece of parchment and asked, “So then… would that be ‘Us the people’ or ‘We the people’?”

Historians tell us a Pennsylvanian named Morris actually wrote the U.S. Constitution. His task was to organize the noble concepts and clear vision put forth by the delegates to the constitutional convention and capture them in imprecise language. Kind of like writing a rulebook. And let’s face it: The Constitution has pitted the writer’s ability to describe against the readers’ ability to comprehend ever since. Everyone seems to have his or her own idea of exactly what it means and some devote their whole lives to changing it.

Historians tell us a Pennsylvanian named Morris actually wrote the U.S. Constitution. His task was to organize the noble concepts and clear vision put forth by the delegates to the constitutional convention and capture them in imprecise language. Kind of like writing a rulebook. And let’s face it: The Constitution has pitted the writer’s ability to describe against the readers’ ability to comprehend ever since. Everyone seems to have his or her own idea of exactly what it means and some devote their whole lives to changing it.

Hey! It’s exactly like writing a rulebook!

Most officials will admit to having a favorite or least favorite rulebook to study. The football rulebooks, for instance, are a load for a lot of readers. It’s not that football is hard to understand; it’s hard to describe because so much is going on in a game. As a result, the rulebook’s level of language is a challenge to some readers. It contains a lot of convoluted statements, carefully written around the underlying definitions, which are critical to understanding them. And often, to answer a question like, “What is a legal block?” you have to pull in information from several different places within the rules. At the other end of the spectrum is something like the volleyball rules. There’s less to control and no intentional physical contact to be dealt with, so the game is fundamentally simpler and the rulebook tends to hang together in more discrete silos. If you want to know about legal net play, for example, there’s usually just one place to look, right beneath a handy heading. Rulebooks evolve differently because of the complexity and challenges of the games they describe.

Rulebook editors have the task of making sense of it all and are a select breed. They’re far from being English majors who once watched a football game. They typically have a distinguished background as an administrator, coach or official and have a passion for keeping their sport(s) current. Despite their own credentials, they call on a wide circle of experts in their sports to make the rules writing process efficient.

Jim Paronto is the NCAA secretary and rules editor for baseball. He says that rules writing is a near-perpetual cycle of observing the game, determining the need to change rules, drafting the new rules coherently, disseminating them and then monitoring the effect: Plan-Do- Check-Act. He travels the country, talking to the umpires, coaches and administrators and listens to their feedback. When he has a rule change to write, he says he favors fewer words over more; simple statements work best. As he drafts rules, he runs them by an inner circle of those people who validate what he’s written and help him steer clear of any misstatements or inconsistencies. Paronto also seeks input from individuals of other levels of the sport, like MLB, because of their own experience with the same issues.

The purpose of his process is to get the rule changes in front of the bi-annual rules committee meeting in bulletproof form. It’s not that he doesn’t want the rules committee, representing the college divisions and oversight groups, meddling with what he’s done; it’s that he wants them to be able to focus on their primary concern, which is the potential effect on them: Will a change create more risk? Will it require more administrative time to manage? Will it take more training time to implement? How much will it cost? Paronto believes that if that group is having trouble doing its job, he hasn’t done his properly, which is giving them concrete language to work with.

Despite an editor’s best efforts, writing rules is sometimes like describing color to a blind person and some changes can create their share of confusion. Paronto attempts to clear that up through the approved rulings he inserts throughout the rulebook. They aren’t rules per se but clarifying examples of how rules are applied, where there’s a chance of misinterpretation. He uses things like the pattern of rule interpretations he’s asked to make and the questions umpires are getting wrong on exams as grist for those rulings. Where there’s smoke, there’s probably fire.

Becky Oakes handles volleyball, swimming and diving, gymnastics, and track and field for the NFHS. Her approach to making rule changes is essentially the same as Paronto’s, but she has different organizational restrictions to work with. First of all, because she has so many sports to administer, she has less time to dwell on any one, even though her numbers of participants might dwarf what’s seen in the NCAA.

She relies more on survey input and state association feedback than first-hand interaction, like Paronto does. As a result, the rules committee meetings have more direct delegate involvement in the writing process. It can take a lot of moderating and leadership ability under those circumstances to keep the meetings on track, but she says the professionalism of the rules committee members is a huge plus. They all play for the same team.

Oakes was asked what keeps her awake at night when it comes to all the updates she’s responsible for in her rulebooks.

“The first thing you look at is whether the change you make is going to affect the safety of the athlete,” she says. “Then, does it give one competitor an advantage over the other and can the officials enforce the rule fairly and consistently?”

How far have we come? In 1938, Sir Stanley Rous rewrote FIFA’s Laws of the Game into 17 articles, contained in a very thin booklet. The world somehow coped with that bare-bones guidance for half a century; using the all-important and unwritten “Law 18: Common Sense” was a great help. As the game grew, however, the carpenters eventually went to work. Where Rous simply wrote, for instance, that a player could not handle the ball deliberately, today’s rulebooks define handle, ball and deliberate in infinite detail, with multiple examples. Which is better? The latest Laws of the Game on the FIFA website is 148 pages long, but it’s the same old game. It seems like rulebooks have gotten fatter as people have cared more who wins. The books often attempt to capture remedies for everything that has gone wrong in games and to explain away every red herring that the hounds dig up. Through it all, editors have to contend with how much information is too much information because too much leads to contradictions and loopholes that are harder to correct than prevent.

Writing a rulebook is an art, practiced by people who have been chosen for their skill to practice it. As an art, it’s certainly no more perfect than science, and we know how imperfect science is. Rulebooks are really very well written; if only they were as well read by all concerned. If officials don’t understand a rule, it’s probably not the writer who’s at fault; it means we still have more to understand and learn.

Trust that the editors have done their jobs well and work at your rulebook until it all makes sense.

What's Your Call? Leave a Comment:

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.