It’s difficult for an official working a national championship game to avoid the spotlight. But during the opening minutes of the 1997 NCAA men’s basketball championship game, Tom O’Neill found himself nearly invisible — and it was more than his nerves could handle.

“I went the first five minutes of the game without putting air into the whistle,” O’Neill recalled about Arizona’s overtime win against Kentucky. “Nothing happened in front of me. I didn’t have a foul; I didn’t have a ball go out of bounds; I didn’t call a timeout. … I started to sweat a little bit. I said to myself, ‘I don’t care what happens … the next foul or violation I see, no matter where it’s at, I’m calling it.’”

Fortunately, O’Neill’s first call of that game was a foul in his primary area.

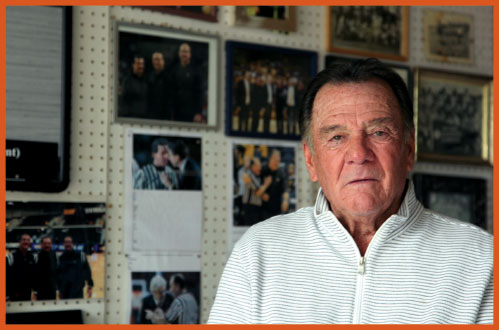

That national title contest concluded his 20th year as a Division I men’s basketball official. Now 24 years later, O’Neill has hung up his lanyard for the last time. For parts of six decades, he worked in more than 20 NCAA D-I conferences. By his count, he tallied more than 3,300 D-I games, which he believes is more games than any other official in NCAA men’s basketball history.

“I want that record,” said O’Neill, whose high profile came mainly through his work in the Big Ten, Big 12 and Southeastern conferences. “College basketball has seen a lot of very good officials, and the number of games we work is one way we are judged. I worked hard to become one of the best officials, so that record is important to me. It’s a distinctive mark of longevity doing something I love.”

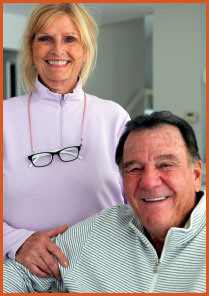

Before his extensive foray into officiating, the native of Calumet Park, Ill., played baseball for Northern Illinois University. He graduated with a degree in physical education in 1967, began a teaching career in Chicago’s south suburbs and started calling grade school basketball games. At home, he and his wife, Vickie, were raising their three sons, Richard, Tom Jr. and Michael.

O’Neill resigned from teaching in 1979 to become the director of recreation for Calumet Park. He also took over as the boys’ basketball assigner for the South Inter-Conference Association (SICA), a conglomerate of nearly 30 high schools in Chicago’s south and southwest suburbs.

“I wanted to help improve officiating,” O’Neill said of the assigner’s job he held for 25 seasons. “I provided SICA with the best officials in the area. Some SICA games had Division I officials working. They weren’t big-time D-I referees at that time, but they were guys with significant college experience. I’d argue against anyone in Illinois who believed their conferences had better officiating than SICA.”

O’Neill’s first D-I game was at Eastern Illinois in 1977, and nine years later he made officiating his full-time occupation. He has worked as many as 112 games in a season, crisscrossing the country from New York to Florida to Minnesota to Texas to Colorado to California.

Building his frequent flyer miles from November through March gave him plum assignments, but it came at the typical expense of family time. While O’Neill monitored post play and airborne shooters, his wife managed their sons’ increasing load with school and extracurricular activities.

“Tom’s travel schedule was a lot,” Vickie, Tom’s bride of 52 years, said. “Having to get three boys back and forth by myself and be there with them was difficult because I couldn’t be in two or three places at once.”

O’Neill saw potential in 1989 to minimize his travel when he received a phone call from Dave Gavitt, then the commissioner of the Big East Conference. Gavitt had ties to the NBA and informed O’Neill the NBA wanted to add him to its officiating staff.

“Dave called at a time when I was ticked off about not getting the Final Four assignment,” O’Neill said. “I talked to Vickie about working in the NBA and had to convince her I would be home more. I was working 80-90 games a year, which meant being on the road 20 nights a month, but with the NBA, I would be gone 13 nights a month.”

“Dave called at a time when I was ticked off about not getting the Final Four assignment,” O’Neill said. “I talked to Vickie about working in the NBA and had to convince her I would be home more. I was working 80-90 games a year, which meant being on the road 20 nights a month, but with the NBA, I would be gone 13 nights a month.”

O’Neill accepted the NBA’s offer for the 1989-90 season, but circumstances beyond his control negated the expected benefit of less time on the road. Before the preseason ended, the league instituted a new travel policy.

“The rule was for the officials to fly into the cities of their games on the first flight of the morning,” O’Neill said. “An official missed a preseason game because of travel issues, and Darell Garretson, the supervisor of officials, changed the rule and made it mandatory for us to fly to our cities the night before the games. That meant I would be gone 26 nights a month.”

O’Neill recalled Christmas 1989 when he “had to leave family dinner in order to catch a flight to the West Coast. Vickie said to me, ‘You know this is not working.’ At that moment, I knew I couldn’t stay in the NBA. I needed her support if I was going to officiate.”

“He promised more time at home, but it turned out to be the exact opposite,” Vickie said. “Sometimes he’d be gone a week at a time, and I didn’t like it.

“He chose to give up the NBA, and I commend him because getting there was one of his goals. He put his family first, and I appreciated that.”

When O’Neill decided to return to the college game, he could not wait until the NBA season ended to see if he could pick up where he left off.

“I began calling my former college supervisors in January,” he said, “and everyone took me back … except the Big Ten.”

Under Commissioner Wayne Duke, the Big Ten did not reinstate officials who left the conference to work in the NBA. When Jim Delaney succeeded Duke in 1990, he and Rich Falk, the Big Ten’s coordinator of men’s basketball officials, revised the policy and welcomed O’Neill back.

“NBA experience shouldn’t disqualify officials from returning to college,” said Falk, who held that position with the Big Ten for 21 years. “We had such high regard for Tom, and his experience combined with the respect he had from coaches, officials and other conference coordinators were big factors in bringing him back.

“Anytime you can get an official who’s worked at the highest levels, whether the top NCAA conferences or the NBA, you know he’s worked games involving the best players and a high quality of play. If they can manage those games and have good reports from the people with whom they worked, those are good indicators they can manage most any situation.”

The NBA situations O’Neill encountered were less stressful than those in college. The longer season made the professional game easier for him to work.

“The players played hard, but their ultimate goal was to be healthy for the playoffs,” O’Neill said. “They weren’t throwing their bodies all over the place. They paced themselves. That’s the difference between 82 games versus 35 games for college teams.”

When O’Neill’s one-year contract with the NBA expired, he hopped back into the NCAA grind for the 1990-91 season. His return culminated in Indianapolis with his first Final Four game. He was pleased to take the sport’s biggest stage but partially displeased about his assignment.

“I hung my head when I learned which game I was going to work,” O’Neill said about the semifinal between Duke and UNLV. “Vegas blew them out the previous year in the championship game, and they were a double-digit favorite. I thought the (North Carolina-Kansas) game was going to be more competitive.

“The atmosphere in the (Hoosier Dome) was electric from the moment we stepped onto the floor, and that got my juices going. When I saw those (60,000) people in the dome, I said to myself, ‘Don’t screw this up! Your family’s here and millions are watching this.’”

Much to O’Neill’s surprise — and anyone else not rooting for Duke — the Blue Devils upset the top-ranked, undefeated Runnin’ Rebels en route to capturing their first national championship.

O’Neill returned to the RCA Dome for the aforementioned 1997 title game. He officiated in two more Final Fours: Florida’s 2007 semifinal victory against UCLA in Atlanta and North Carolina’s 2009 championship win against Michigan State in Detroit. He had plenty of preparation for those games, as he was a frequent official in some of the NCAA’s most heated basketball rivalries, such as Indiana-Kentucky, Kansas-Oklahoma and Illinois-Missouri.

The one series omitted from his list is Duke-North Carolina because the Atlantic Coast Conference is the lone power conference he did not work. That hole in his résumé may be proof of his unquestioned success and high demand.

“I didn’t have any Saturdays open to give to the ACC,” he said, “and if you couldn’t give some Saturdays to the coordinators for those major conferences, you probably weren’t going to work in those leagues.”

“I didn’t have any Saturdays open to give to the ACC,” he said, “and if you couldn’t give some Saturdays to the coordinators for those major conferences, you probably weren’t going to work in those leagues.”

Dale Kelley was one of those coordinators who commandeered many of O’Neill’s Saturdays. As the coordinator for five D-I conferences, he had enough games to keep O’Neill occupied.

“Tom was always on top of his game,” said Kelley, who accumulated 25 years as the coordinator for the Big 12, Sun Belt, Southland and Ohio Valley conferences and Conference USA. “I never worried about a game he worked for me. I knew it would go well, and if anything happened that needed resolution, I was sure Tom could handle it.”

Like O’Neill, Steve Welmer spread his officiating wings across a wide swath of the country. The two worked in the same conferences, so their names appeared together in many of the same box scores.

“We had seasons in which we worked 40 games together,” said Welmer, who totaled 31 years at Division I before retiring in 2011. “We clicked the first time we worked together. We had a background playing college baseball, and we liked to have a beer or two. Our officiating philosophy and calls were similar, so teams could count on our consistency. We liked to let the kids play a little bit.”

That old-school axiom of “letting the kids play” may be fading. Consistency now comes from constant video review, a trend O’Neill and some of his peers think has made officiating less art and more science.

“Hank Nichols (former national coordinator of men’s basketball officials) emphasized advantage/disadvantage,” O’Neill said. “If the contact didn’t affect the players, let it go … let them play through some contact.

“This current generation doesn’t do that. I’ve worked with guys who make ticky-tack calls at the end of a 20-point game. When I ask about it, they say, ‘If I pass on that, I’ll get an incorrect call.’ That’s unfortunate because most young officials are looking over their shoulders every time they blow their whistles. If I were in my 20s or 30s, it would drive me nuts!”

“This current generation doesn’t do that. I’ve worked with guys who make ticky-tack calls at the end of a 20-point game. When I ask about it, they say, ‘If I pass on that, I’ll get an incorrect call.’ That’s unfortunate because most young officials are looking over their shoulders every time they blow their whistles. If I were in my 20s or 30s, it would drive me nuts!”

Fellow longtime official Ted Valentine echoes O’Neill’s sentiment.

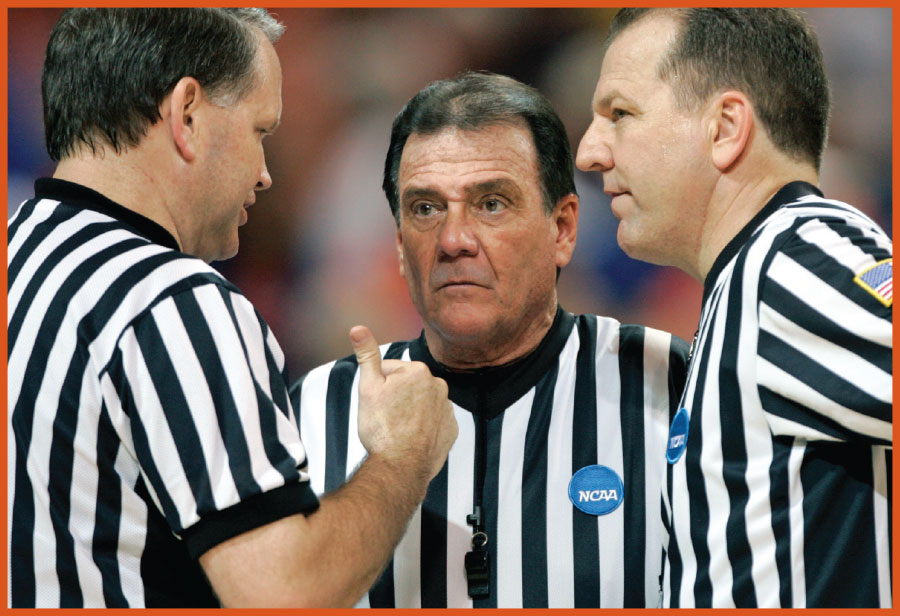

“Tom and I came up in an era when we officiated more on basketball instincts,” said Valentine, a veteran of 39 Division I seasons and one of O’Neill’s Final Four partners in 1991 and 1997. “This current culture of officiating has too much micromanagement, and that’s not the best way to work.

“Tom can officiate by the seat of his pants. He knows when to blow the whistle and when not to blow it. He officiated the game the right way. He always had a good feel and total command for the game.”

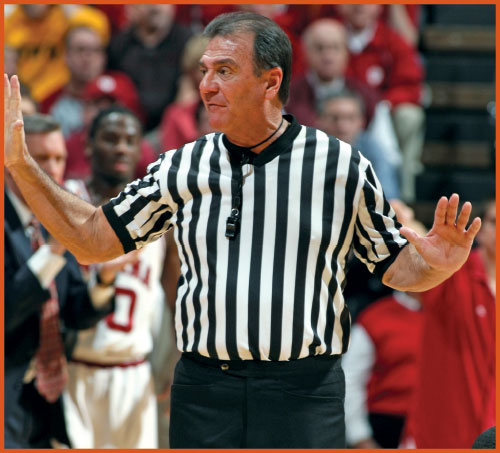

Keeping command of the college game entails handling coaches, and O’Neill excelled at it. He relished the salty language that emerged occasionally.

“I enjoyed the coaches who swore more than those who didn’t because I have the tendency to swear,” he said. “If they swore at me first, I felt I could swear back at them, but I wouldn’t swear at coaches who didn’t swear.

“I was never afraid to give a technical foul. It’s like any other call in the game. Coaches need to know if they get out of line with 30 seconds left in the game, I might whack them.”

O’Neill may have taken a hard stance with coaches, but Kelley lauded his approach as the kind other officials should emulate.

“The scrutiny on officials has much to do with their mindset in how they interact with coaches,” Kelley said. “It takes a special person to wade through all those factors and get the job done, and Tom rose to the occasion time and time again.”

Welmer has seen those occasions more than he can count. O’Neill was no imposing figure, but his presence portended his fiery competitive streak.

“He’s fearless … he’s gutsy!” Welmer said. “No coach or player could intimidate him. He wouldn’t let anyone or any game get the best of him. He knew people didn’t come to the games to watch him; he was there to be a part of the game and make sure he got the calls right.”

Without definitive data, one can only estimate the number of fouls and violations O’Neill whistled in his 44 years, including 80 games in 28 NCAA tournaments. He did not linger on questionable calls, except for a traveling violation near the end of the Villanova-North Carolina game during the 2005 Elite Eight.

“It’s the only call I’ve ever taken home with me,” he said, “and that’s because it was my last call of the season. I didn’t hold on to stuff like that, but without another game to work, I had all offseason to think about it.”

His offseasons feature the Tom O’Neill Basketball Officials Camp, and its return in 2021 after a pandemic-induced hiatus will be the 46th edition. For the past 15 years, his operating partner has been Harry Bohn, the head basketball clinician for the Illinois High School Association (IHSA) and an assigner for Chicago-area high school and college conferences. The camp gives him the best of two worlds.

“I coordinate what’s taught throughout the state for the IHSA’s certified clinic,” Bohn said. “We bring in the top young D-I officials as observers so our campers always get the latest information on mechanics.

“Tom’s status as one of the elite officials in the country brings credibility to the camp. We’ve attracted some of the best officials from Illinois, Wisconsin and Indiana. It’s a Godsend for me as an assigner because I can watch officials before hiring them.”

Dan Dorian attended his first O’Neill Camp a few weeks after graduating high school in 1986. It was the first step of an officiating journey that has led him to the Mid-American, Big Sky and Western Athletic conferences.

“Dan Chrisman (O’Neill’s former business partner) noticed me at the camp, and when he introduced me to Tom, he said, ‘This guy doesn’t know what he’s doing, but he knows the game,’” Dorian said. “From there, Tom started teaching me how to officiate. He loaded me up with freshman and sophomore games in SICA.”

After a few years of sturdy high school schedules, Dorian developed an itch for Division I exposure, but his mentor would not help scratch it.

“I started asking if I could go to a D-I camp, and Tom told me I wasn’t ready,” Dorian said. “I worked high school ball for 12 years and a couple years of NAIA and Division III before he told me I was ready to go to a D-I camp.

“He gave me the green light in 2003 and advised me to attend Dale Kelley’s camp. The following year, Dale hired me and things took off for me from there.”

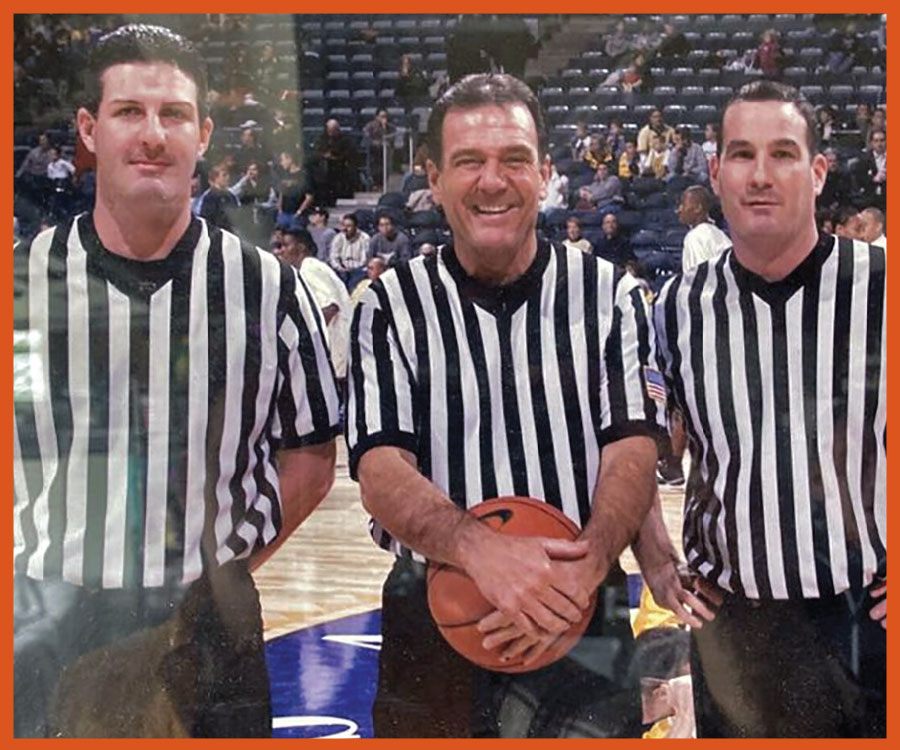

The business of officiating has been a boon for O’Neill and his family, and business became personal on Nov. 30, 2001, when Marquette hosted Texas Southern. In what he calls his proudest moment, O’Neill officiated with two of his sons, Rick and Tom Jr. It marked the first time a Division I officiating crew comprised a father and two sons. A couple years later, Michael joined Rick and Tom Jr. to become the first trio of brothers to officiate the same Division I game.

“We had a natural ease working with one another,” said Tom Jr. “I knew neither one of them would sell me down the river or call my supervisor to say, ‘This guy stinks!’ I was comfortable with them because we’d been taught the same principles about officiating.”

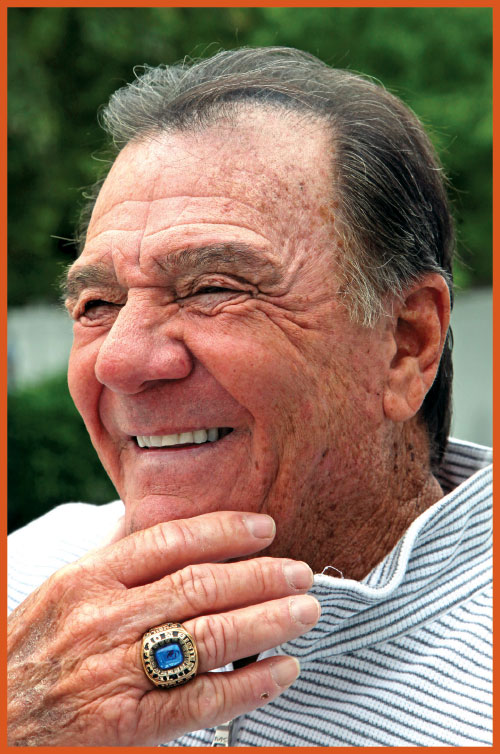

A different sense of paternal pride had been O’Neill’s prime inspiration in the final years of his career. His father, Joe O’Neill, was his biggest fan, and when he died in May 2019 at age 97, so did much of O’Neill’s motivation to continue officiating.

“My dad loved watching my games,” O’Neill said, “so he was my main reason for working the last few years. He had something to look forward to, and I liked providing him that pleasure. I prided myself in working for him. When he passed, I lost that edge.”

With basketball now in his rearview mirror, O’Neill has more time for diamond action, of both the softball and baseball varieties. His remaining sports obligation lies with USA Softball, the nation’s governing body of softball, formerly known as the American Softball Association. As the commissioner for northern Illinois since 1984, he coordinates tournaments for 3,000 girls’ fast-pitch teams and men’s 12-inch and 16-inch teams.

Youth baseball now is O’Neill’s favorite pastime. The former college shortstop and second baseman helps coach his grandsons, Anthony and Nicholas.

“It’s a treat for me to watch them grow up and to share baseball with them,” O’Neill said. “I can relive my boyhood memories through them as they get better playing the game.

“I achieved everything I wanted to do in officiating. I met a lot of great people and had a lot of fun. Not many people get to do what they love for as long as I did and leave on their own terms. I think things turned out pretty good.”

Marcel Kerr is a freelance writer from Chicago.

What's Your Call? Leave a Comment:

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.