Update: June 14th, 2019 – View the court’s ruling

Some of history’s bloodiest conflicts were started over a small insult. A pastry chef not receiving compensation for his business being looted during a riot led to a war between Mexico and France in 1838. In 1925, a Greek soldier was shot after allegedly crossing the border into Bulgaria while chasing after his runaway dog. The United States and England almost went to war a second time in 1859 over, get this, a pig. What a group of athletic directors in Pennsylvania thought would be a mundane letter to sports officials in December 2012 has turned into a full-blown legal battle in 2019, being played out inside a Washington, D.C. courtroom, with national implications.

Led by a group of relatively unknown lacrosse officials in western Pennsylvania, the Allegheny Lacrosse Officials Association (ALOA) are seeking more of a say in how officials do their jobs and how they are compensated for their work. The D. C. Circuit court’s ruling, which could come at any time, would mean a historical changing of the landscape on how high school sports officials are classified. It could lead to the chance to negotiate higher pay, better working conditions, a voice in state playoff assignments and more of a direct connection in general to state high school associations throughout the country.

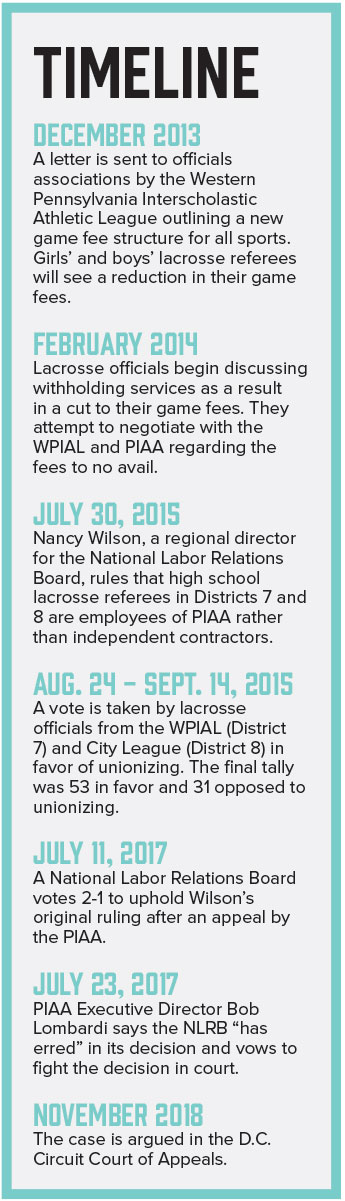

While there have been dozens of cases in the past on this same topic when it comes to youth and high school officiating, none have ever risen this far up the judicial ladder, which is why the impending ruling is keeping everyone from state association leaders to your local YMCA basketball referee curious, excited or afraid. The ALOA, which consists of about 140 members, began its quest in the summer of 2013, after officials associations across District 7 received an email from John Grogan of the Western Pennsylvania Interscholastic Athletic League (WPIAL) outlining a new officials’ game fee structure for all sports. Fees in girls’ lacrosse were reduced 25 percent, from $120 to $90, while the rate for boys’ matches was reduced about 30 percent, from $130 to $90, according to Ed Guminski, a veteran lacrosse official from Edgewood, Pa. Moreover, a five-year wage freeze went into effect. The letter did not go over well with many officials associations.

“This letter came out of the blue and smacked us in the face,” Guminski said.

A counterproposal was sent to the WPIAL by lacrosse officials, requesting not a pay cut, but rather a $5 raise for varsity matches each of the next three years. Guminski said meetings with the WPIAL were fruitless. The raise proposal was never discussed, he said.

Referee obtained a copy of the email reportedly sent by Grogan, who when contacted on Feb. 6, declined to be interviewed for this story. In the email, Grogan, speaking on behalf of the WPIAL Athletic Directors Association, explained a committee had been established to review the pay scales for officials in September 2012. The committee voted in November 2012 on a new standard pay scale that would cover the next five years.

“We had our chapter president and our chapter assigner sort of suggest to our representative with the athletic directors that we might be taking some kind of vote at our next chapter meeting on whether or not we want to withhold services,” Guminski recalled.

The WPIAL representative, according to Guminski, tried to allay the officials’ fears that the numbers in the letter were deceiving and the pay cut was not as severe as it appeared. The officials weren’t convinced, and began contemplating their next move. They wanted to form a union, but could not do so without first being classified as employees instead of independent contractors. A group of officials in the ALOA got together and began researching their options. They figured their best shot was to take their case before a labor agency to provide them some legal standing.

In 2015, Nancy Wilson, regional director for Region 6 of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), ruled the ALOA, of the Pittsburgh area, should be considered employees of the Pennsylvania Interscholastic Athletic Association (PIAA). The PIAA appealed that ruling to the NLRB, which upheld the regional director’s finding on a 2-1 vote (see sidebar on pg. 23). The PIAA took matters a step further, asking a federal appeals court to review the ruling.

THE 2-1 NLRB DECISION

The July 11, 2017 decision by the National Labor Relations Board affirmed the regional NLRB director’s finding that the Pennsylvania Interscholastic Athletic Association (PIAA) had not met its burden of proving that the officials are independent contractors rather than employees. An appeal of that decision is pending before the U.S. Court of Appeals in Washington, D.C.

The board split 2-1 in its decision. The conclusions of the panel are instructive.

In support of finding that the lacrosse officials should be considered employees were board members Mark Gaston Pearce and Lauren McFerran. They concluded that “the officials’ employee status is well substantiated by the extent of PIAA’s control over the officials, the integral nature of the officials’ work to PIAA’s regular business, PIAA’s supervision of the officials, the method of payment and the fact that the officials do not render their services as part of an independent business.”

They further found that “the connection between the officials’ skills and PIAA’s essential functions, as well as PIAA’s role in developing those skills, further supports a finding of employee status.”

Pearce and McFerran concluded that even if the aforementioned points were inconclusive, “we would still find that the overall weight of the factors favoring employee status exceeds that of the factors suggesting an independent contractor relationship.”

Dissenting Opinion Questions Jurisdiction and Finding

Board Chairperson Philip Miscimarra dissented on the decision, questioning both the NLRB’s jurisdiction and the previous ruling that the lacrosse officials should be considered employees of the PIAA. He believes the officials to be independent contractors based on the autonomy and authority to referee games as they see fit. He also believes, political subdivisions — effectively local governmental units within a state — are exempt from the National Labor Relations Act.

“I remain convinced that the Board should grant review regarding the potential lack of jurisdiction here because this case gives rise to substantial questions about whether the PIAA is a political subdivision of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,” he said. “Also, I believe that the petition should be dismissed in any event because the PIAA lacrosse officials are independent contractors rather than employees,” he added.

Miscimarra said he further disagreed with his colleagues’ finding that the officials should be classified as employees, but should instead be ruled independent contractors because of, “the distinct skills they possess, the fact that they are paid on a per-game basis, and their freedom to take other work.”

Miscimarra concluded his opinion by stating:

“Moreover, finding the lacrosse officials at issue here to be independent contractors is consistent with the vast weight of precedent holding that PIAA officials in other sports, and similar officials in other states, are independent contractors based on similar considerations,” Miscimarra concluded.

Both sides laid out their case during oral arguments in November 2018: the PIAA asserting the lacrosse officials should be considered independent contractors (ICs); the NLRB arguing the officials should be treated as employees with the Office of Professional Employees International Union (OPEIU) intervening in support of the two earlier rulings by the NLRB.

In its filed brief, the PIAA made three major points to deny enforcement of the NLRB order:

- The PIAA argued the order should be denied enforcement because it “expressly relied throughout the opinion on a decision” (FedEx Home Delivery) that was in direct conflict with the D.C. Circuit Court’s holding in a previous FedEx case that was vacated by the court (see sidebar on page 26).

Even if the NLRB’s decisions were entitled to rely on “FedEx in defiance of this court’s orders,” the PIAA called on the D.C. Circuit Court to reverse the NLRB’s finding that PIAA-registered lacrosse officials were employees, not independent contractors. The board departed from precedent “as well as more recent cases decided by the board and this Circuit,” the PIAA brief argued.

- Common-law agency factors “strongly support a finding of independent contractor status, including the officials’ complete exercise of independent judgment in officiating games, PIAA’s lack of supervision of the games, the skills required of officials, their supply of their own tools, the short duration of their performance of work, their method of payment, the parties’ mutual understanding of independent status, and the officials’ entrepreneurial freedom to officiate at times and fees of their own choosing and in leagues and careers outside PIAA,” the brief added.

- Finally, the “Board erred in failing to find that PIAA is a political subdivision within the meaning … of the NLRA (National Labor Relations Act),” the brief stated. Such a finding is compelled by Pennsylvania statutes dealing with interscholastic athletics accountability, “which re-established and mandated that PIAA perform the public function of overseeing the state’s system of interscholastic athletics,” PIAA argued. Political subdivisions are exempted from the NLRA.

The NLRB countered in its brief, arguing for a finding of employee status for the lacrosse officials based on the following facts:

- The PIAA controls the means and manner of the officials’ onfield performance and related duties.

• The officials are an integral part of the PIAA’s operations and are not engaged in distinct businesses.

• The PIAA directs the officials’ work while reviewing and supervising their performance.

• The PIAA certifies the officials and trains them in the required skills on an ongoing basis.

• The PIAA regulates the system of compensation for the officials and dictates their postseason pay.

• The officials lack significant opportunities for entrepreneurial gain or loss and are not rendering services in connection with independent businesses.

During oral arguments, the two sides laid out their positions while answering questions from the judges.

The PIAA asserted in the courtroom that the lacrosse officials are ICs, not employees and referenced a “standard business test” used to make that determination. The PIAA termed the officials “independent skilled specialists” with no supervision at the game site in terms of “being told what to do as the game goes on. Call them as you see them.”

In terms of payment of officials, the PIAA said during the hearing that the schools pay the officials, not the PIAA, except for the state playoffs. Officials pursue other careers and work in other full-time jobs in addition to their officiating duties, the PIAA added.

In terms of payment of officials, the PIAA said during the hearing that the schools pay the officials, not the PIAA, except for the state playoffs. Officials pursue other careers and work in other full-time jobs in addition to their officiating duties, the PIAA added.

The NLRB argued the PIAA pays officials directly during playoff games, and there is a degree of supervision regarding their performance, including discipline and removal from future games depending on performance. The PIAA sets the standards on how the officials should officiate and conduct themselves on the field, the NLRB argued.

The NLRB also asserted that the PIAA generates millions of dollars in revenue, certifies and trains officials, and that officials take the field representing the PIAA, even wearing the PIAA patch on required uniforms that are approved by the PIAA to be worn.

The NLRB also asserted that the PIAA generates millions of dollars in revenue, certifies and trains officials, and that officials take the field representing the PIAA, even wearing the PIAA patch on required uniforms that are approved by the PIAA to be worn.

As the attorneys made their case, the judges delved into the issues, focusing on some key areas. While the case is currently under consideration, the following questions could be a factor in how the judges will look at some of the most critical issues:

- Who pays the game fees?

• The length of the officiating season — if the season is only a few months long, can the officials be considered full-time employees? - Officials working full-time jobs elsewhere. If an individual has a full-time job, how could he or she have employee status with the PIAA?

- Can officials officiate non-PIAA events? (The answer is “yes.”)

- Are there any places in the country where high school officials are considered employees of the state?

Since arguing the case in November, the NLRB has overturned its standard for deciding whether workers are employees or independent contractors. In a 3-1 decision on Jan. 25, the NLRB returned to its long-standing independent-contractor standard, reaffirming the board’s adherence to the traditional common-law test. In doing so, the board clarified the role entrepreneurial opportunity plays in its determination of independent-contractor status, as the D.C. Circuit Court has recognized. The decision overrules the FedEx decision, which modified the applicable test for determing IC status. It is uncertain at this time how the new NLRB interpretation impacts the PIAA lacrosse case. The new NLRB interpretation does show, however, that the complicated matter of IC status continues to change.

Lacrosse wasn’t always a PIAA-sanctioned sport. In the days when clubs were the assigning body, a crew of two officials was paid between $125-$130 for a girls’ match and between $130 and $135 for a boys’ contest. Guminski explained there is always a disparity in pay between boys’ and girls’ matches because under the rules for boys’ matches, the clock is stopped more often, making for a significantly longer game.

As fate would have it, Guminski had been a 29-year employee of the NLRB. He knew from his NLRB experience what distinguished an employee from an independent contractor. Minor league baseball umpire and fellow lacrosse official Mario Seneca was an organizer for the OPEIU. The two got together and weighed their options.

“Between (Seneca) and myself … we thought, ‘Let’s at least take a look at whether or not we’re employees or independent contractors.’ As an employee, you have a lot more rights under federal law. As independent contractors, you essentially have nothing,” Guminski said.

And with that, union authorization cards were solicited between the girls’ and boys’ chapters, gaining enough signatures to file a petition requesting a hearing with the NLRB regional director. The NLRB’s Wilson ruled on July 30, 2015, that the officials were indeed employees of the PIAA and not independent contractors.

“All registered sports officials employed by Pennsylvania Interscholastic Athletic Association who officiate at PIAA-sponsored boys’ and girls’ lacrosse games in the geographic areas of Pennsylvania designated as ‘District 7’ and ‘District 8’ by the PIAA constitution; excluding all office clerical employees and guards, professional employees and supervisors as defined in the Act, and all other employees,” the ruling read.

The ruling also meant the officials could vote to join a union. Officials cast union ballots via mail between Aug. 24 and Sept. 14, 2015. Needing a simple majority from those who voted to approve unionization, the measure passed, 53-31, with 11 of the ballots being challenged.

On July 11, 2017, the NLRB upheld Wilson’s decision on a 2-1 vote.

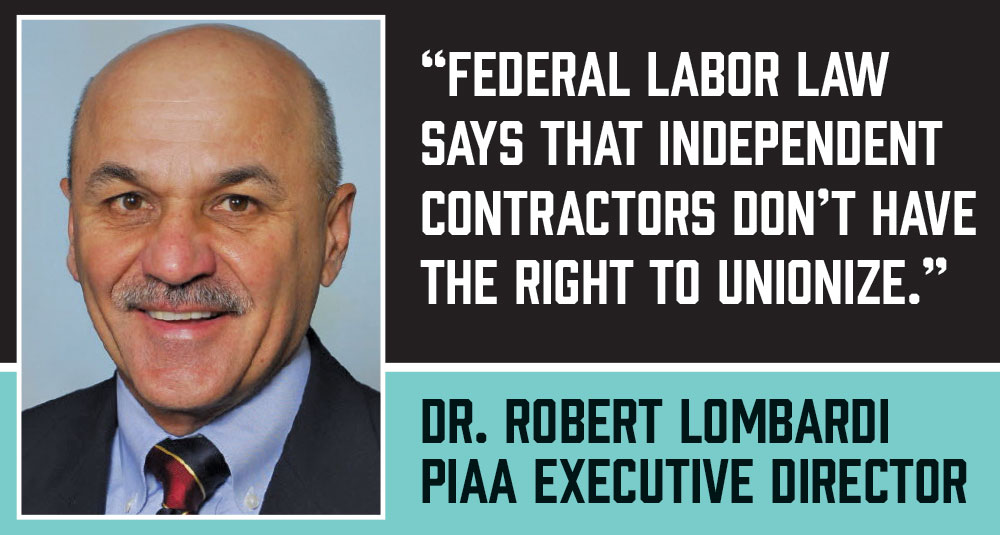

Due to pending litigation, PIAA could not comment on this story. However, PIAA Executive Director Dr. Robert Lombardi did issue a public statement in August 2015 after the initial NLRB ruling. Lombardi told LancasterOnline.com:

“Federal labor law says that independent contractors don’t have the right to unionize,” Lombardi said. “And we believe that these officials are independent contractors. I believe the officials have been misled by the union. PIAA does not control regular season game fees; those are negotiated between the officials and the schools, even the NLRB regional director (Wilson) said that in her decision several times.”

NFHS Paying Close Attention to the Case

While all of this is being played out in the courtroom, the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS), the governing body for high school sports in the country, is keenly aware of what this case could mean for it and the state associations the NFHS advises. Executive Director Dr. Karissa Niehoff, who became the sixth executive director in NFHS history last August, said she is watching the case closely.

Before Dr. Niehoff took her position, the NFHS sent their legal counsel, John Black, to hear the appelate case arguments first-hand in Washington. The NFHS even filed an amicus brief on the case before the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, supporting the PIAA. The NFHS called for the court to refuse to enforce the NLRB’s decision finding the lacrosse officials employees and instead should rule they are independent contractors.

“High school sports officials in the United States have traditionally and routinely been considered independent contractors,” the NFHS argued, particularly given the nature of high school sports.

“Limited seasons, unpredictable schedules, low budgets associated with non-revenue-producing activities, and the need to master the rules of different sports, all combine to make it difficult to pursue high school officiating as a full-time career with a single employer. Instead, in the Federation’s experience, high school sports officials tend to have other careers, and to officiate on a per-event basis for a flat fee only when it suits them and their outside schedules,” the NFHS said in the brief. “The flexible, long-standing and mutually beneficial relationship these officials have with high schools often leads to express acknowledgments, as in the parties’ contracts here, that the officials are working as independent contractors.”

Based on the eventual outcome of the case, Niehoff said the NFHS can provide information to states in terms of what issues to consider when doing business with officials.

“Because each state is a little bit unique, the Federation itself is just watching very closely to see what the decision is, and then see what momentum builds from there. We’re kind of in a stay-tuned mode,” Niehoff said. “We’ll probably provide some information, some insight, and perhaps some guidance to help state associations interpret what that outcome might mean for them once the D.C. Circuit makes its ruling.”

Educational Value of High School Athletics

If the court finds against the PIAA, the NFHS believes it may disrupt officiating nationwide and threaten what it believes is the educational mission of high school athletics.

“In the Federation’s experience the overwhelming majority of these high school officials do not officiate as a career or as a full-time pursuit with a single employer. Nor could they as a practical matter — the very structure of high school athletics makes this effectively impossible,” the NFHS argued in the brief. “Depending on the sport, athletic contests can occur at odd times — weekends and evenings — at widely varying locations, rather than at a set location during regularly scheduled hours. While there are many opportunities to officiate high school athletic contests generally throughout a state like Pennsylvania, an individual school’s contests are limited, and each sport is limited to a specific season.”

The NFHS continued to argue in the brief that even though there are officials who officiate multiple sports, each sport has different rules that require a different skill set, and those sports take place during different parts of the year.

Typically, state associations do not pay officials for regular-season work. Sports officials are instead paid by the high schools themselves, according to the NFHS. Additionally, the petition said participation is voluntary, and, “The officials, not the associations, control when and where they work, one of the key hallmarks of an independent-contractor relationship. And there are no limitations on any official’s ability to work elsewhere. …”

The PIAA and other state associations monitor officials in a general way, “attempting to maintain a basic level of competence,” the NFHS said in the brief, but they “do not supervise individual contests. Any attempt to actively control the officiating activities of so many individuals scattered across different sports in all parts of their states would be far beyond state associations’ capabilities or budgets.”

The PIAA and other state associations monitor officials in a general way, “attempting to maintain a basic level of competence,” the NFHS said in the brief, but they “do not supervise individual contests. Any attempt to actively control the officiating activities of so many individuals scattered across different sports in all parts of their states would be far beyond state associations’ capabilities or budgets.”

The NFHS said officials’ high school contracts “expressly state what should be plain: High school officials are acting as independent contractors, not employees, and all concerned parties have traditionally ordered their affairs in recognition of this obvious truth.”

Length of Employment

How much time during the year you are working for an employer is only one of the “many things to look at” in the case, according to Shaun Francis, OPEIU international representative (Francis left his position with OPEIU in January 2019), who played a major role in getting the case this far. He said officials are mandated by the PIAA to attend rules meetings, told what chapters they can join, what uniforms to purchase and where they can buy them. He believes because the the PIAA controls these things, it has “a well-maintained workforce of employees.”

Francis added that officials don’t have a voice with the PIAA on who goes to the playoffs and the structure regarding who gets those games was created by the PIAA. In other states, like Louisiana, Oregon or Texas, there are statewide officials associations.

“It’s voluntary. They’ve organized themselves. It’s a statewide contract. That’s all we want to do here,” Francis asserted. “Officials in this case don’t think they can trust the PIAA, so they went down the court path.”

To organize as a union, the officials must be considered employees first, Francis explained. The law does not allow for ICs to unionize. He said this was the first vital step presented to the lacrosse officials and they agreed.

Francis was a minor league baseball umpire himself, working in the New York-Penn, Midwest and Florida State leagues. He served as president of the Association of Minor League Umpires (AMLU) from 2007 to 2012. He then became executive director of the AMLU from 2012 to present, where he has successfully negotiated the last two collective bargaining agreements with Minor League Baseball.

Costs and Skill Level

The “cost” of officials implies many things — training, travel, insurance — just to name a few. Attorney Don Collins, commissioner of the San Francisco section of the California Interscholastic Federation and Alan Goldberger, a sports attorney who focuses on officiating duties, have long followed the issue of whether sports officials should be classified as independent contractors or employees. Some would say that when the layers of the onion are peeled back, the issue of who bears the cost of paying for officials sits at the core. Collins and Goldberger agree that the issue is complex and isn’t going away soon, and that who bears the cost will drive much of the debate.

To be successful as an official, a high level of skill is necessary. That means assigning individuals or agencies must do a good job of matching officials with the right abilities to work contests at a higher level of talent, speed and execution. You can’t just throw an official on a game, according to Goldberger and Collins. The need to match good officials to the right games is an issue that argues against a union-type environment. It’s also a factor that makes the officiating industry slightly different from other hiring situations.

“Some see assigning bodies as a hiring agency or temporary help, so they don’t look at the high level of skill necessary for officiating,” Collins said.

Full-Time or Not?

The nature of officiating at the amateur level is that the position is not full-time. Most officials at the small-college level down through middle school games officiate as a secondary job and work full time during the day. That’s another major factor leading officials and associations into independent contractor status. Officiating is suited to independent contractors, according to Goldberger.

“How many people in the general population have a job where they can get off at 2:15 in the afternoon to umpire a 3:30 baseball game? Only a certain segment of the population can do this,” he said.

The right to control a person’s work remains important in many interpretations of the law: “Does an employer have the right to tell you how to do a task?” he asks.

Goldberger used the example of a baker and a basketball game to further his analysis. “If someone works for a baker and there needs to be a level teaspoon put into the batter, an exact amount of jelly inserted into the dough, and the flap must be folded in a special manner to ensure every tart turns out to specifications, then the baker probably has an employer relationship with an employee,” he began. “But if it’s a basketball game and the players are beating the hell out of each other and 47 fouls are called, you may well have an independent contractor situation, because you can’t prescribe how the official should exactly rule in each of those foul situations. Nor can an employer necessarily dictate how an official officiates throughout a game,” he asserted.

Top-Down Control?

In the bigger picture, Francis asserted that the PIAA is a top-down structure with full authority over the officials’ assignments. He said with that type of structure in place, it would be difficult at best to have a fair negotiation with the PIAA.

“A union would force them to negotiate fairly,” Francis said.

Most officials across the nation are ICs, but not all. In Pennsylvania, an official must apply to the PIAA, pay a fee, the PIAA certifies the official, the official is assigned to a chapter and the PIAA sets up the required meetings.

Even if the officials are ruled to be employees, 30 percent of the officials in Pennsylvania would have to sign cards asking for union representation, then there would be a hearing, according to Mel Schwarzwald of the law firm Schwarzwald, McNair and Fusco, which is representing the union. If the lacrosse officials win the case and they choose to pursue union representation, the NLRB conducts the election and the union would negotiate a contract, he explained. Schwarzwald addressed a potential work stoppage if the officials become members of a union.

“Neither employers or employees want strikes,” Schwarzwald said. “Most contracts have an arbitration and grievance provision. If there ever is a strike, the court could issue a ‘back to work’ injunction. We want officials working.”

“Sometimes you need to flex your muscle,” added Francis. “The OPEIU has been urging the lacrosse officials to pull back, while the officials are wanting to walk out on their own.

“Whether they unionize or not, the officials have leverage and should stand up for what they are worth,” Francis asserted. “Standing together gets results. Our job is to work with the officials. They are not being treated fairly. There are safety, security and game fees issues.”

The Path Forward

Many officials do see themselves as independent contractors, in that they are their own profit center. They must keep track of their expenses and file taxes. They take care of their own training and must figure out insurance.

When it comes to unions — whether one makes sense for a group of officials or not — depends on who you talk to, where it is in the country and what would be the benefits. Most officials associations probably don’t lend themselves to a union environment due to the nature of the officiating industry when it comes to game assignments and paying dues to cover the additional overhead costs of a union, according to Goldberger. More paperwork is associated with a union as well.

“Unions will cost more,” Goldberger explained. “That said, bargaining with a union for wages and benefits for someone who might come onto school grounds twice a year — if it doesn’t rain — is probably not something school sports would blandly accept.”

Officiating is a unique occupation. It does not necessarily lend itself to the “next guy (or gal) up” automatically getting the next game assignment. Officials associations bargain for game fees and assigners have arguably the best knowledge of the skill set each official can bring to a game.

How Far Would the Union Go?

“The union is representative, not dictating,” Schwarzwald said.

If the final ruling favors the lacrosse officials, a contract would be taken to the union to vote on, and if it passes, the union would help with enforcement.

“If this case is not won on appeal, it will be up to the 140 lacrosse officials in the Pittsburgh area to decide on what’s next. This case is not solely for them. The goal is statewide representation for all sports. The legal questions have to be resolved,” Francis said.

The OPEIU would determine if other officials or officiating organizations would be willing to join the union. If the case is lost, there are at least two key questions the officials might consider: Do they want to organize a voluntary association? Can they call for a work stoppage themselves?

“That will be determined by the officials on the ground. The officials asked us — the union — to come in. We (OPEIU) have provided legal representation with no dues collection,” said Francis, noting the OPEIU has 100,000-plus members nationwide.

Francis said the concerns of many who are against the idea have been rampant but most of it has been based on misinformation. He said at no time has he or anyone else said they wanted vacation time, sick days, retirement or worker’s compensation if they are deemed employees. Regarding any benefit package if the officials are ruled as employees, Schwarzwald said officials would not automatically be entitled to benefits. They would not expect health care benefits. There would be a negotiation, and a continuance of current insurance that the PIAA provides for games.

“Most officials have full-time jobs and insurance coverage through that job. If the union is brought in, it would negotiate a realistic contract, seek ratification and then enforce the contract,” he said.

Many people are skeptical of unions. Issues like seniority and bumping people from jobs are concerns. The question of whether only the senior officials get the top games if the officials were unionized was asked.

In other contract situations, “senior officials have been negotiated out, and the best officials have been negotiated in,” Francis said.

That type of provision would likely get put in writing if the lacrosse officials win the case and choose to unionize. Francis said MLB uses numerical rankings for umpires to determine playoff games and such.

Since health care and some other situations like pensions and retirement issues don’t apply in this case and are not under consideration at this time, Francis said the PIAA will still look pretty much the same as it does now.

If a union comes in, there would likely be renegotiations with the PIAA every two to three years on things like game fees, travel costs and possibly playoff game assignments, and whether officials must go to a yearly meeting in Harrisburg, which is the state capital.

“Officials would have a voice, which is all we ever wanted,” Francis said. “The officials aren’t going away.”

Jason Palmer, Dave Simon and Jeffrey Stern, are editors for Referee magazine.

Legal History of Employee Versus Independent Contractor

The longtime labor debate of employee versus independent contractor status was first in the federal court system of the United States during President Harry Truman’s administration. Since then, the country has struggled to decipher the convoluted legal language in a way that is consistent and easy for all to understand.

In June 1947, Albert Silk, doing business as the Albert Silk Coal Co., sued the United States to recover taxes alleged to have been illegally assessed and collected from Silk for the years 1936 through 1939 under the Social Security Act. The taxes were levied on Silk as an employer of specific workmen, some who were hired to unload railway coal cars and others who made retail deliveries of coal by truck. Silk paid those who worked as unloaders an agreed price-per-ton to unload the coal. The men came to the yard at their own leisure. They used their own tools, set their own schedule and worked for others at will. Silk owned no trucks himself, so he contracted with workers who had their own trucks to deliver the coal at a uniform price-per-ton.

Both the trial and appeals court ruled the workers independent contractors. However, the U.S. Supreme Court overruled the lower courts and said the workers were employees by stating: “The right to control how work shall be done is a factor in the determination of whether the worker is an employee or independent contractor.” The Supreme Court went on to say, “A contract is not conclusive evidence of independent contractor status. A contract, no matter how ‘skillfully devised,’ should not be permitted to shift tax liability from a business to its agent in a manner which frustrates the purpose of federal employment tax laws.”

The Supreme Court added the degree of control exercised by the business along with the independence of the worker over the operational details of the work must be analyzed in each situation when rulings by the court are made.

A more recent case involved drivers for FedEx. Until 2011, FedEx contracted directly with independent contractors. In doing so, FedEx saved on taxes, health care costs, fringe benefits, pensions and other costs had the drivers been employees of one of the world’s largest delivery companies.

The drivers claimed that as employees, they were owed overtime pay and reimbursement for expenses, among other benefits. Several drivers in about 40 states sued FedEx for failure to pay overtime and a host of other claims, including fraud, under the laws of each state. It eventually became part of a larger class-action lawsuit.

The drivers argued they did not have nearly as much control over their work as FedEx was claiming. FedEx controlled what kind of vehicle the drivers drove, how they dressed (uniform), had grooming requirements and even regulated how drivers smelled, according to the suit. FedEx also controlled when and which packages would be delivered on any given day, and at what times. Likewise, FedEx designed the drivers’ workloads to ensure they worked between nine and 11 hours a day. The drivers were also reviewed by a FedEx manager four times a year to ensure the company’s policies and standard for customer service was being met.

The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals found FedEx’s control was enough to make the drivers employees rather than independent contractors under Oregon and California law. FedEx eventually settled the case in 2016 for $226 million, ending more than a decade of litigation.

The question has also come about as it relates to high school and youth sports officiating. In May 2011, the governor of the state of Washington signed a bill into law that categorized youth sports officials as non-employees of their associations.

A similar bill was also passed in Oregon that same year, where the state’s unemployment offices were attempting to tax officials associations when officials were laid off from other jobs and listed officiating as their main source of income. The state’s Department of Labor claimed that the officials were employees of those local associations.

Back in 1994, three officials in California — Bob Summers, Don Collins and Jim Jorgensen — pushed to have a bill passed after the state’s Employment Development Department (EDD) attempted to go after associations for taxes on unemployment. Within a year, a bill was passed and signed by then-Gov. Pete Wilson that classified sports officials as excluded from the labor codes’ definition of “employees.” The bill also spelled out an agreement by which the EDD would adopt new regulations specifying the circumstances under which sports officials could be specified as employees. The EDD adopted the new regulations in July 1996.

In 2009, an appeals court in Tennessee confirmed that officials were independent contractors and not employees. The decision came about in a case where a high school baseball player was injured after being hit by a foul ball during a game as the player was sitting on a bucket outside the dugout. The umpires were sued because players must be in the dugout during play, according to NFHS rules. A trial court ruled the umpires were independent contractors and the appeals court upheld the ruling.

In 2008, Lisa Gill, former executive director of the Indoor Sports Center in Eau Claire, Wis., was stunned when a part-time official who was paid $2 a game to assign officials and an additional $20 per game to officiate, filed for unemployment benefits. Laid off from a full-time job, the individual listed the facility as a source of income. An unemployment agency determined the sports center was in violation of the state’s employment laws. An administrative law judge overturned the decision on appeal.

There have been dozens of court cases around the country regarding this issue throughout U.S. history. Currently, 14 states have ruled sports officials to be independent contractors, but only eight have passed legislation making amateur officials ICs.

Update: June 14th, 2019

The DC Circuit Court of Appeals decision ruling sports officials as independent contractors in PIAA v. NLRB.

View Full Screen by click box [ ] above.

What's Your Call? Leave a Comment:

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.