As their school bus approached their home on Holman Avenue that November morning in 1986, Chris Guccione and little brother Steven were distracted by the emotional voice of their mother saying goodbye to them at the front door. This was no ordinary farewell as she repeated, “I love you guys! I love you! Never forget I love you! I love you!”

Still, boys will be boys. It was supposed to be a routine day for the Guccione brothers at Longfellow Elementary School in Salida, Colo., and they wouldn’t completely process the distress that was inside their mother’s head or the anguish that was in her voice until years later.

“It was like, ‘OK, this is weird. We’re going to school. Bye,’ said Chris Guccione, who was a 12-year-old sixth grader at the time.

While at school that day, Guccione’s beloved father, Geno, stopped by with a sobering question. “Where’s your mom?” Geno asked his son. “Home, I guess,” Chris responded. “I don’t know.” Geno said furniture, extra cash and other possessions had been taken from the house and there was no sign of a woman who had bid her sons such a passionate farewell just a few hours earlier that morning. Something was terribly wrong and, as time would reveal, there would be no happy ending to this unwanted family drama.

“We had no idea where she went,” Chris said. “And then like three days later, she calls and says, ‘Hey, I’m all right.’ But for my dad, his wife just picks up and leaves … what an awful feeling.”

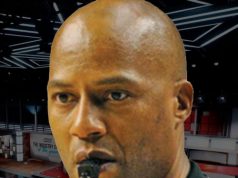

It was at least as painful for Chris. His mother, outside of surfacing briefly a few times in his life, was gone for good, rendering the eldest of her two sons a mess emotionally during many of his vulnerable younger years. The time would come when Guccione would marry his high school sweetheart, become a first-time father at the age of 41 and establish himself as one of the most accomplished umpires working in the major leagues, but all that came only after sorting through the baggage that was crammed inside his head. It was a prolonged emotional state that was so at odds with the serenity where he was raised.

Salida remains a peaceful town with fishing holes, lazy streams and a plenty of wilderness for a kid to lose himself. But Guccione would never completely experience the unrestrained joy of being a boy with his buddies in those expanses of wonder. Losing a mother as he did has a way of leaving permanent scars within a boy’s consciousness and it took years for him to come to terms with that void.

“I don’t really tell many people this, but I had a terrible separation anxiety,” Guccione said. “I could not have my dad leave my sight for the longest time. It was so hard for me that I couldn’t concentrate in school. I would break out crying … I was scared to death.”

And all the while, he mostly kept his feelings to himself as he tried to live a normal boyhood with Steven and best friends Shane Armenta and Darrin Howell. This was simply something he rarely wanted to discuss.

“It wasn’t a topic of conversation,” said Armenta, two years younger than Guccione. “He didn’t mention it a whole lot, but I knew it devastated him. And Geno was deeply depressed. Even several years later when we were older, her name just really didn’t come up a lot. I know that several times I wanted to talk about it, but I didn’t want to hurt the guy.”

There was an unspoken bond between Howell, whose parents were divorced, and Guccione. Mutual therapy came in the form of fishing together.

“I think that was a tough time in both of our lives,” Howell said. “I think we helped each other and just kind of fed off it. We didn’t really talk about it much. I knew it bothered him but we knew we were both in the same boat.”

Guccione, a temperamental boy who would find peace when he started walking a spiritual path, will never be able to thank God enough for his dad. It was Geno, suddenly thrust into a single-parent role, who would always be there for a confused Chris. So much so, in fact, that the first words Guccione said when interviewed for this story were, “I would like to talk about my dad because he is a big part of my life.”

Where does one start with Geno, a smallish man who nevertheless walks with a towering emotional presence to this day at the age of 70? He arrived in the United States from the small village of Gesuiti, Italy as a 12-year-old immigrant in 1958 and went on to serve a tour in Vietnam as an engineer in 1971 and ’72. Since then, he has supported his family with the modest wages he has earned as a maintenance worker for the Salida School District. His income was limited, but the love he has had for his two sons was consistently written with a blank check as the three members of this family felt their way through life.

“There’s nothing worse than a young kid going through that, with their mother taking off on them,” said Geno, who speaks with a thick Italian accent. “It was tough, but I said, ‘We’ll get through it.’ Chris was a quiet kid who kept everything inside. He never did talk about that. But little by little, we got through it.”

One common denominator between father and son was baseball

One common denominator between father and son was baseball, for which Geno developed a strong passion as a boy in Italy. By the time he relocated to America, his beloved New York Yankees were in the final chapter of their Ruth-Gehrig-DiMaggio-Mantle dynasty for the ages and Geno made baseball a part of his sons’ lives. It was almost as if Mickey Mantle had a spiritual place at their dinner table as Chris was constantly regaled with stories about the switch-hitting legend. Ironically enough, a boy who would grow up to handle raging managers and players in major league games was once a hothead himself. That goes back to when he was 5 years old, when he lied about his age so he could play for his father on a youth baseball team in Salida.

“There was a play at second. The umpire made a call and I threw a fit,” Guccione said. “Well, my dad came out to calm everything down and he ended up getting ejected. So they made him sit in his car out in the parking lot and, like an inning later, I said something I shouldn’t have and I had to leave the game, too.”

There was a second irony, given the profession Guccione would one day choose. He was a gifted athlete, but only had a passing interest in baseball despite his early participation. The Colorado Rockies were years away from joining the NL as an expansion franchise and it was John Elway and the Denver Broncos who dominated a boy’s imagination when Chris was growing up. He willed himself into a run stopper as a 150-pound interior defensive linemen for the Salida High School football team as a junior during the 1990 season and would become a feared pass-rushing end after bulking up as a senior. “He was a heck of an athlete,” Howell said.

Salida introduced a varsity baseball program during Chris’ senior season in the spring of 1992. Geno was named the Spartans’ head coach and leads the program to this day. Chris instead concentrated on track and placed third in the Colorado state finals in the shot put.

As for his beloved Broncos, he would go to extremes to be sitting in front of a television during those years when Elway was working his magic. Take the time he and his future wife, Amy, were returning from a shopping trip and he asked her to pull into her parents’ driveway on the way home during the last minutes of a tense game.

“The Broncos were playing Tampa Bay and we were racing back from shopping because I wanted to watch some of the game,” he said. “There were like 30 seconds left and I told her, ‘Just pull in here.’ I was on the passenger side and I shut the door, but I didn’t really hear it latch. My wife was looking the other way and, as she backed up, the door hit this huge 1968 Ford truck in the driveway. She bent the door completely back where it was up by the front fender. I said, ‘The heck with it. I’m going to watch the game anyway.’ The Broncos ended up losing, so I went back out there, took a couple of sledgehammers and pried the thing back on there. My father-in-law still has the truck to this day and the door still doesn’t shut right.”

When Guccione was 12, he had developed enough of a resume to take up umpiring his little brother’s youth games as a way to make a few extra dollars. Using the instincts that those who work with him today single out as one of his greatest attributes, the kid held up well. He had a decent command of the rules and just remember this: One didn’t mess with Chris Guccione, even at that tender age. Guccione stood firm, even that time when all hell broke loose when he called a hitter out for having one foot out of the batter’s box.

“I was not intimidated, not at all,” he said. “The thing is, in the little town of Salida, you know all the parents and they would scream at you and try to convince you otherwise. I didn’t listen to them. I didn’t yell back because I had a lot of respect for people who were old enough to be my parents, but I would not put up with any of their sass.”

After graduating from high school, Guccione enrolled at Western State College in Gunnison, 65 miles away over Monarch Pass, but that wasn’t for him. He was back home after the fall semester and spent his time working for a cousin painting houses and continuing to work local baseball games in the summers. Guccione ended up working so many games with friend Chris Clarkson that Clarkson’s father, John, suggested the boys consider enrolling in an umpire school. But there was a catch. Each young man had to figure out how to raise what Guccione remembers as $3,000 for the Jim Evans Academy of Professional Umpiring in Kissimmee, Fla.

“I had no idea there was even such a thing as an umpire school,” Guccione said. “We really couldn’t afford it, but because of the help of the community, we ended up raising enough money to get to umpire school in January 1995.”

Guccione held his own at the academy during the five-week course, even though there was some adventure. Like the time at Cocoa Beach, Fla., when he and future major league umpire Brian Knight bolted to their locker room with outraged members of a team hot on their heels. After his indoctrination at that academy, Guccione went on a 14-year journey until he secured a permanent position in the major leagues in 2009. He would endure an endless diet of baloney sandwiches on so many dusty backroads connecting minor league towns. Being an aspiring major league umpire is a dicey proposition, waiting for a call that might never come. Guccione endured as well as he could. Just ask Knight.

“When we were in the Midwest League together in 1996, we were in Clinton, Iowa, and he had the plate and I had the bases,” Knight said. “There was a runner on first and there was a blooper over the shortstop’s head. In that situation, when a runner is going from first to third, the home-plate umpire rotates out to third base to take that play. Well, I got caught up in the action and I forgot that he was coming to third, so I was at third also. There was a play at third base and, with every ounce of energy I had, I called him safe. And as I look up, I see Chris standing behind third base just as emphatically calling him out. We locked eyes in sheer horror after realizing what we had just done. Well, as it turns out, the guy was out by like a foot. There was another umpire crew listening to that game on the radio as they were driving between cities and they heard it. We couldn’t hide from anybody.”

Guccione and Knight spent that season in a rented red Nissan Altima, traveling endless back roads. They alternated time at the wheel as the music of the Grateful Dead and the Dave Matthews Band, the respective favorites of Knight and Guccione, filled the dead air when conversation waned. And all they could do is continue calling them as best as they could under the hot summer sun while waiting for a break. Would they ever make it?

“We used to have that conversation all the time,” Knight said. “One of the major league supervisors at that time was Phil Janssen and every night at the home plate meeting, one of us would say, ‘Hey, I think I see Phil Janssen up there.’ That was our way of telling each other, ‘We’re tired, it’s hot, but we’re still going to work our butts off because Phil Janssen might be in the crowd.”

Guccione almost quit in 1998, during another prolonged separation from Amy, whom he married that year. Credit Amy with a crucial assist when worse came to worst. That came during the 1998 season when Guccione had his fill of being separated from Amy for months at a time and wanted to give it all up. Perhaps it hit home the hardest when she graduated from the University of Colorado Health and Science Center and he was in the middle of nowhere working another minor league game in the Texas League.

“She comes up to Wichita, Kan., for three or four days and, at the end of this trip, I finally told her, ‘I’m done. I’m leaving. I’m sick of this career. I just want to be home. I’m tired of the road.’ She basically told me, ‘Suck it up!’ She said, ‘We’ve worked too hard for this, we’ve come too far for you just to come home now.’”

Long ago, Guccione had lost a mother, but he wouldn’t lose this. The break of day was just around the corner and he was assigned his first major league game in 2000. Nine years later, he would achieve permanent status and continues to evolve into one of the best of the best. He is determined to be one of the most accurate umpires in the major leagues. In 2014, 14 of his 15 calls that were challenged by managers were upheld on video review. He also worked his first World Series in 2016 as the Chicago Cubs won a seven-game showdown against the Cleveland Indians.

“He’s just got natural ability,” Knight said. “It’s just amazing. He’s one of the best umpires I’ve ever worked with and it’s no coincidence that he just got the World Series last year. He is one of the best we have. A lot of it is just natural God-given ability, I believe. He’s always worked very hard, but for some guys, it just comes a little more naturally.”

Ted Barrett, another veteran umpire who would become a major influence on Guccione as he started walking a more spiritual path, sees a counterpart who will one day be remembered as one of the best ever.

“He’s tremendously gifted,” Barrett said. “He’s got tremendous instincts, which is something you can’t teach. It’s kind of rare. I consider myself a very good major league umpire and have a good resume of postseason success and I don’t possess the instincts for officiating that he has. I have to work extremely hard to get into the right position and it’s something that comes natural to him. So when you take instincts, you add a passion for the job and you have the passion to get better both as a person and as an umpire, you have a unique combination that makes up Chris Guccione.

“A huge part of his story is perseverance,” Barrett continued. “He and Rob Drake, if you look at the amount of games they worked (in the minor leagues), they were well over 1,000 games before they got hired, which is unprecedented. For them to just keep pressing on … the thing I remember with Chris was there was never any complaints, there was never any, ‘poor me.’ It was just a numbers game.”

Guccione is at peace now under the guidance of Barrett, who helped start a ministry group for umpires. The Gucciones welcomed their first child, daughter Gemma, into the world in October 2015. Quite simply, a young man who lost so much that November day in 1986 has found so much. And it all goes back to Geno.

“I’m so proud of him,” Geno said. “I tell both of my kids that I’m proud of them.”

To say the least, that goes double for Chris.

“He’s someone who has been tested, has raised two boys the best that he could by himself on a minimal salary working maintenance in Salida, Colo., and he’s been there encouraging me and supporting me my entire life.”

What's Your Call? Leave a Comment:

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.