T

he prohibition against engaging in play that is dangerous or likely to cause injury to oneself or an opponent has been a part of NFHS rules (12-6-1), NCAA rules (12.2.9) and the IFAB Laws of the Game (12.2) since those rules and Laws were first formulated.

The safety of all players is always of paramount importance to the officiating team and care must be taken to ensure, as much as is possible, players do not endanger themselves or their opponents during the match.

The NCAA rulebook provides a detailed definition of the term “dangerous play.” It is “any action, with or without physical contact, likely to cause injury to oneself or an opponent.”

What should the referee look for in determining the existence of dangerous play? All that is required is for the official to decide if an unintentional act of physical contact or attempted contact is dangerous to the person committing the act or to an opponent. This is not always easy and there are few written guidelines other than approved rulings in the rulebook to assist in making a proper determination. Great discretion is given to the officials in the application of this rule.

Early rules/Laws before the 1900s enumerated certain acts, such as tripping or pushing, were illegal but they were silent concerning dangerous play. The first appearance of dangerous play in IFAB related to an attempt by an attacker to kick a ball being held by the goalkeeper. Acts such as this must be dealt with promptly and may even warrant a sanction such as a caution (yellow card). The penalty for dangerous play is an indirect free kick from the spot of the infraction. However, in the example just noted, if any actual contact is made with the foot against the keeper, the offense escalates to a much more serious act and would be considered kicking, resulting in a direct free kick which is a penal offense and possible ejection (red card) for serious foul play.

There are many other acts that may be judged as dangerous. Unintentionally lying on top of the ball (by a field player) is not in itself dangerous and should not be penalized unless an opponent is near and such action prevents the player from playing the ball. This is an example of dangerous play being called by the referee for the purpose of preventing an injury to the innocent player who happened to fall on the ball.

There is a misconception prevalent in the game that a player who is lying on the ground cannot play the ball. This is generally untrue, unless an opponent is quite close, in which case the referee must determine the possible danger to the player on the ground.

Scissors or bicycle kicks are permitted in the game unless an opponent is within playing distance and the kicker’s foot is, in the opinion of the referee, dangerously high so as to endanger the opponent. If no one is within playing distance, there can be no offense. A player should not be automatically penalized for making a great scissors-kick play just because he or she made the play. This can be a very exciting part of a match.

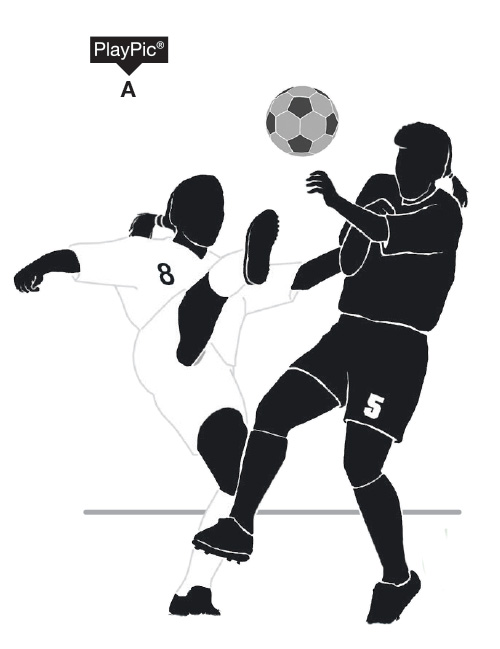

The high kick (raising the foot above waist level, as shown in PlayPic A) is another act that may or may not be dangerous play. Determination must be made as to the proximity and danger to an opponent (or in the NFHS rulebook — any player). A player may commit dangerous play against a teammate in a match played under NFHS rules.

The high kick (raising the foot above waist level, as shown in PlayPic A) is another act that may or may not be dangerous play. Determination must be made as to the proximity and danger to an opponent (or in the NFHS rulebook — any player). A player may commit dangerous play against a teammate in a match played under NFHS rules.

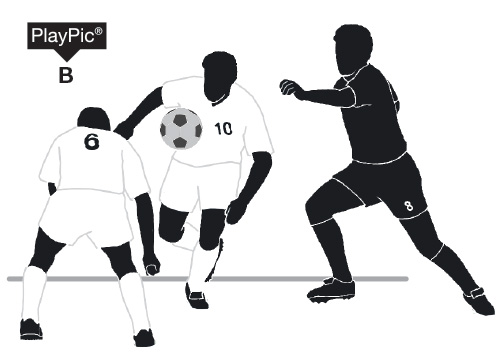

The opposite of a high kick is the low header (as shown in PlayPic B). This is a situation when a defender dives with his or her head in a low position to contact the ball but is in close proximity to an opponent who may be trying to kick the ball. This is clearly dangerous play since the low head could be kicked and the player severely injured. The referee should always allow an exception for the goalkeeper who is attempting to dive on the ball, however.

The opposite of a high kick is the low header (as shown in PlayPic B). This is a situation when a defender dives with his or her head in a low position to contact the ball but is in close proximity to an opponent who may be trying to kick the ball. This is clearly dangerous play since the low head could be kicked and the player severely injured. The referee should always allow an exception for the goalkeeper who is attempting to dive on the ball, however.

Various types of tackles that otherwise may appear to be clean and acceptable can be deemed dangerous. For example, a sliding tackle where the foot contacts the ball, but where the tackler’s other leg is raised up with cleats showing, might be called dangerous by the referee. A plunger tackle, where the player jumps onto the ball with two feet together, could cause injury to a nearby opponent. This should also be called a dangerous-play offense.

One other act, quite prevalent today, is the goalkeeper who has possession of the ball and raises a knee to fend off an opponent. If the referee feels this is dangerous to the opponent, the foul should be signaled. It may be best to avoid having an indirect free kick right in front of the goal. A technique might be to merely verbally warn the goalkeeper the first time this occurs to refrain from such acts. This should prevent future acts. In many instances, the raised knee may be a technique used to gain additional height when the goalkeeper jumps. The referee must determine if this act was part of a jump to obtain height or a means of intimidating an oncoming opponent.

One somewhat rare type of dangerous play is when a player attempts to trap the ball and it lodges between the player’s legs. Opponents cannot play the ball without fouling the player in possession. This creates a dangerous situation to the player and must be called as dangerous play.

The situations listed are merely examples. Other actions will occur in a referee’s career that will no doubt require instant interpretation and discretion in order to ensure the safety of the players. Dangerous play can cause injuries to an opponent and the referee must deal with it when it occurs.

What's Your Call? Leave a Comment:

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.