It takes extraordinary strength to take charge of a Super Bowl – strength of will, of desire and of conviction. Ed Hochuli has done it twice. But the NFL referee, renowned for his skill and recognized for his muscles, has found certain weights in his life too heavy to lift.

The little brother, grass-stained, sweat-soaked and sore, gazed into a pair of eyes that were acknowledging him with unwavering conviction that November night in 1967, not with the older-brother indifference he had long known. His moment had come.

The fortunes of Canyon Del Oro High School hung precariously in the balance at Amphi Field in Tucson, Ariz., and precious little time remained on the scoreboard clock. With the ball resting at its opponent’s 12 yardline, Canyon Del Oro had just one more shot to punch in the winning touchdown against archrival Amphi, the established older and somewhat haughty high school in the Tucson School District.

Senior quarterback Chip Hochuli called a 34-counter off-tackle play as the Dorados, wearing the same green-and-gold colors as Vince Lombardi’s Green Bay Packers, circled for one last huddle. And then Hochuli stared into the eyes of Canyon Del Oro junior running back Ed Hochuli, the little brother who always had to try so much harder to win over the older kids on the block, and spoke to him as an equal for one of the first times.

“Can you get it in, little brother?” Chip Hochuli asked with a sense of cool urgency.

Of course, Ed Hochuli could get it in. Even though he was not particularly fast, elusive or strong, what that then-16-year-old kid had was a will to win and a passion to please. And at that one memorable moment, big brother was depending on little brother for one of the only times that Ed Hochuli can remember to this day.

“I was already, at a much earlier age, a competitive person,” Ed Hochuli says. “I was somebody who wanted to be good and I wanted my brother to be proud of me, and I wanted my parents to be proud of me.”

The Amphi interior defense was no match for Ed Hochuli after he secured the handoff from the brother who was entrusting so much to him. The little brother slipped through a crease and burst toward the end zone on wildly churning legs to score the winning touchdown in a game that was simmering with so much emotion.

Going on 37 years after Hochuli pulled off his No. 41 jersey that glorious Friday night in Canyon Del Oro’s victorious locker room, he has yet to stop twisting and turning, grinding and pushing and scratching and clawing for those few extra yards in life.

DRIVE

As he heads toward his 54th birthday on Christmas Day (at the time of this interview), Hochuli is going to win and nobody’s going to stop him. The older brother he revered isn’t calling the plays anymore, but just give Ed Hochuli the damn ball and he’ll take care of it from there.

He’s got to succeed. It’s part of who he is.

“As far back in my childhood as I can remember, I have always been a Type A personality, if you will,” he says. “I’ve always had that competitive drive. One of the things that shaped my competitiveness was the fact that I had an older brother.

“I was the second of six kids and I had an older brother who was a better athlete than me and I was always trying to keep up with him.”

That explains why Hochuli was plastering teammates with some big-time licks during a no-pads practice for his high school all-star team in the summer of 1969. Hey, Hochuli just had to compensate for being a marginally talented athlete who didn’t necessarily feel he belonged among that elite talent.

That explains why Hochuli studied his textbooks as a law student in the 1970s while blood drained out of his arm week after week. Hey, selling plasma helped put food on the table for his young family.

And that explains why Hochuli stands in front of a mirror during every football season practicing signals, and why he analyzes 15 hours of tape a week and studiously perfects his enunciation to Cary Grant precision. Hey, while he may be one of the most recognized and respected referees in the NFL, he lives by the creed that once you stop getting better, you start getting worse.

While Hochuli is disciplined, he also freely admits that vanity drives him, too, and is at least partly responsible for his famously chiseled physique. “I’m vain, for one thing, about the way I look,” Hochuli says. “I want to look good. What I did was become a runner. After college, a friend of mine talked me into running a 10K and so I started doing that and that led to marathon running. I ran 12 marathons. After I got into the NFL, there wasn’t time,” says Hochuli, who remains an avid weightlifter. “I still ran and still do to this day, but nowhere near that mileage because I don’t have the time.”

Being perfect was always acceptable to Hochuli, but he couldn’t resist striving for more. And he has, sometimes against his better judgment.

DIVORCE

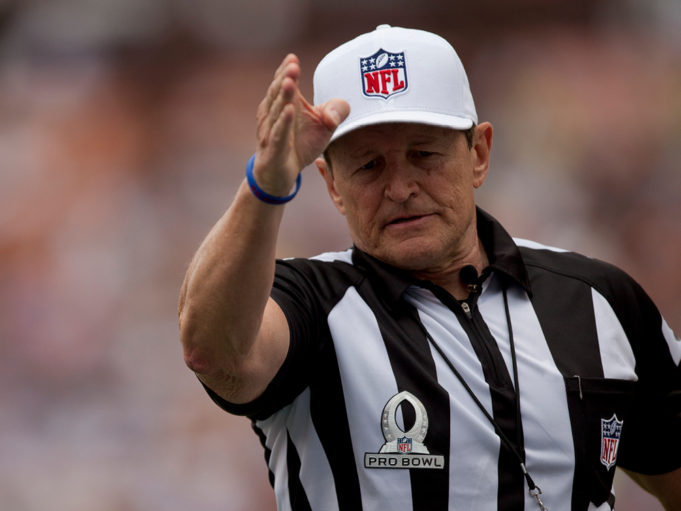

After becoming an NFL official in 1990 and heading up his own crew by 1992, Hochuli has given a striking identity to a profession that is often marked by anonymity in black and white stripes.

The man with the precise mannerisms, the mesmerizing voice and the well-toned body is a celebrity in zebra stripes. Former NBA star Charles Barkley once approached Hochuli in an airport with the same reverence as so many kids have approached Barkley. He is frequently stopped in restaurants, malls and airports for his autograph.

Hochuli is a star.

And yet he has paid an enormous price for what he has achieved. He recently was divorced for the second time within 15 years, which inspired him to really reflect for the first time on whether all he has achieved has been worth it.

As his officiating career continues to soar – Hochuli worked his second Super Bowl last January – he is pausing to take stock.

“Fourteen years ago, I got divorced from my first wife and I think one of the principal things that led to that was that she and I grew apart,” Hochuli says. “We got to the point where we were different people and we really didn’t know each other. The only thing we had in common was five kids.

“The reason that happened – and I blame myself for this – was that of all the things that I was involved in, I made them too important. My law practice, for example, was too important to me and I worked too many hours and too hard to try to develop that practice. And my family life suffered.

“By the time I got into the NFL, I married my second wife and then the NFL took over. There was a lot of travel and a lot of time. Most people don’t realize how much time is involved. Four of the five nights I would be home, I would be sitting there watching film rather than spending the time with my wife.

“So that starts to take away and chip away at that marriage. I really attribute that competitive nature to be a major downfall in both of those relationships.”

Has it all been worth it to Hochuli?

BLOOD

It was 1972 and Hochuli was pushing his way through life with the same passion with which he pushed through that Amphi defense and with the same passion he patrolled the field as an overachieving linebacker at the University of Texas-El Paso.

Attending law school was demanding enough, but there was also the matter of providing for his young wife and new daughter. So after classes at Arizona, he worked a swing shift at Chapman-Dyer Steel until nearly midnight. Five hours later, he would awaken to stack 400 copies of theTucson Daily Citizen into the back of his dark blue 1959 Volkswagen and then toss papers out the window to waiting porches in the early morning darkness.

And then he was off, twice a week, to a Tucson blood bank, where Hochuli rolled up his sleeves to sell more of his plasma. He was already giving his heart and soul. What was a little blood?

“I’d go down there twice a week, stand in line with all the winos and give blood plasma,” he says. “I remember laying there on the table with my law books, studying with all these winos around me giving blood plasma. I could make, I think it averaged out to be $17 a week. I did that all through law school.”

Hochuli was so driven to succeed that he pursued any lead that would enable him to better provide for his family. When Dean Metz, one of his former high school coaches, suggested to him one day that he consider officiating youth football games for some extra cash, the first seeds of Hochuli’s memorable officiating career were planted.

“Within a year, I realized how much I enjoyed (officiating) and how challenging it was,” says Hochuli. “I had just lost that competitive player aspect of my life and I found another way to compete in football. That’s why it got in my blood and I fell in love with it so much. But the big thing for me in the beginning was that I could make 50 bucks.”

Since then, his careers in law and football have run concurrently, consuming him as he advances in both fields. Somehow, he managed to work his way up the ranks as an official even as his law career was threatening to chew him up and spit out the pieces when he relocated to Phoenix after graduating from Arizona.

“I hit the wall after I had been practicing for about three years,” he says. “I got my college transcripts and I was very, very close to leaving the practice and going back and getting my teaching degree. That was kind of my second love. I think I would have enjoyed being a high school teacher and working with kids.

“And then, when I was about to do that, one of my partners, Bill Jones, starting talking to me about starting a law firm, so I went and did that instead.” These days, Hochuli’s Phoenix-based law firm, Jones, Skelton and Hochuli, employs 75 lawyers.

CHALLENGE

Meanwhile, Hochuli was working his way up through the ranks of junior college to the Big Sky Conference and then to the Pac-10. As always, he was driven and reached back for everything he could to succeed.

“Before the ’89 season, I put in an application to the NFL. I was young and I figured if I got in the NFL, it would be six, seven years later,” Hochuli says. “And so I put in the application and just never thought about it again. I thought I was too young and too green and not good enough and I never heard a word that anyone was scouting.

“So when I got a phone call from the league after the 1989 season, I was just absolutely flabbergasted. I thought they made a mistake, that they had me mixed up with somebody else.”

Luck and tragedy worked in his favor. Luck came when he was assigned to be a back judge on the crew of Howard Roe, who passed on to Hochuli his ideals of organization, precision and being analytical. Tragedy came when longtime referee Stan Kemp was diagnosed with Lou Gehrig’s Disease, providing an opportunity for Hochuli to pursue the role of a referee that he coveted, yet had only started working in the World League of American Football. He hadn’t been a crew chief since his days working small college football.

“I remember I had worked a game in Tokyo as a back judge and I came back and it was a Wednesday,” Hochuli says. “I got a phone call from (then-senior director of officiating) Jerry Seeman and he told me he wanted me to be in Denver on Saturday to referee Denver’s first preseason game.

“And, boy, I’ll tell you what, I didn’t sleep a wink. You talk about nervous.”

Still, it was a nervousness that Hochuli cherished. Once again, a challenge was presented to the man. And Hochuli doesn’t back down from any challenge.

SPOTLIGHT

It was Thanksgiving Day in Irving, Texas, on Nov. 25,1993. The Dallas Cowboys were leading the Miami Dolphins, 14-13, during a rare Texas snowfall. Pete Stoyanovich lined up for a 41-yard field goal in the final seconds that would give the Dolphins a victory over the defending Super Bowl champions.

Stoyanovich’s kick was blocked as the capacity crowd erupted in cheers. Chaos ensued. The Cowboys’ Leon Lett inadvertently touched the loose ball before the Dolphins’ Jeff Dellenbach alertly pounced on it.

What was going on here?

Hochuli, in his second year as a referee, was on the spot and he loved every tension-drenched moment. Before a national television audience, he seized the moment with the same passion that he seized that football from Chip Hochuli that November night in 1967.

That was only my second year as a referee and it was a bizarre situation with the snow,” he says. “And then this play happens right at the end of the game. There are seven of us out there and we each have got our own thing to watch and nobody knows everything that happened on a play.

“On that particular play, I have no idea what happened. I’m watching the kicker and the holder and I’m watching what happens to the ball afterward. So I get together with the three guys and each one of them tells me a piece of what happens. Nobody knows the whole story.

“They tell it to me and everybody’s waiting. You know the cameras and everybody are waiting. So I stay back with them and say, ‘OK, as I understand what you’re telling me ..’ and I walk through what they say. And then I say, ‘OK, then this is what we’re going to do.’

“I went out and I flipped that mike on to explain. We’re in Texas Stadium in Dallas. You could have heard a pin drop in there. I can’t remember another time when I ever heard it so quiet in a football stadium. Everybody was just hanging on every word.

“That was a big, big moment for me.”

The Dolphins retained possession. And Stoyanovich converted a 19-yard field goal with one second remaining to give the Dolphins an improbable 16-14 victory.

A star was born in the football officiating profession that afternoon, a celebrity in zebra stripes. It’s just that when Hochuli looks into a mirror, he sees not a celebrity, but that grinder of a kid who so desperately wanted to please his older brother.

“I don’t acknowledge the role,” he says flatly. “I think there are a lot of great referees who we’ve got in the NFL and there are a lot of great referees who we have in college. I mean, I worked with guys in college who are better officials than I am.

“I think I am recognized as one of the better officials. I certainly am one of the 17 NFL officials who gets a lot of TV time and I think I stand out a little bit because I work out and because I probably talk more than most of the referees.

“That’s just my style. It’s probably because I’m a lawyer and it’s probably because I’m comfortable speaking publicly because I’m a lawyer.”

And yet, while he doesn’t acknowledge the role, that doesn’t mean he doesn’t savor the position.

“I enjoy the fact that there are people who like me as a referee,” he says. “I hear from a lot of people and I enjoy that. Like anybody, I like praise. Probably because of my personality, I thrive on that more than other people.

“That’s part of the reason I’m driven, because I’m trying to get praise and recognition. I’m sure some shrink would have a field day with me.”

DAMAGE

During Hochuli’s long and steady ascent to the top of his two professions, damage has been done.

In his dogged pursuit to succeed, there has sometimes been a considerable price to pay. As president of the NFL Referees Association, Hochuli was at the forefront while negotiating a collective bargaining agreement in 2001 that grew nasty. A particular regret for Hochuli is a threatening letter he wrote to college officials, warning them not to work as replacement officials in the event of a strike.

“I think I made a lot of enemies in the contract negotiations three years ago,” he says. “That was a perfect example of everything I do. I try to win and I think I stepped on a lot of toes and I think that I offended a lot of people, officials around the country, people in the league office.

“But I still think as I look back that I wish I would have handled that in a different way. Not that I wouldn’t have tried as hard, but there was the infamous letter I wrote that I sent out to a bunch of college officials across the country and, as I look back on it now, I think, ‘Boy, I sure didn’t word that one very well!’”

What has caused Hochuli to reflect more than anything, though, are his two failed marriages. He has maintained a wonderful relationship with his six children (five with his first wife) and six grandchildren, but sometimes Hochuli can’t help but wonder whether there was too high a price to pay for his success.

“I wish I would have done more balancing in my life,” he says. “I’ve done a very, very poor job of balancing things, of picking my fights and knowing that I should put equal time into this as I do into this.

“I’m very happy with the relationship I have with my children. I can’t imagine anyone else having a better relationship with his six kids than I do. The biggest success I’ve had in my life is not my law practice and it’s not my career in the NFL. It’s clearly my relationship with my kids and what great people that they turned out to be.

“So that’s the one truly successful thing I feel good about is my children.”

If Hochuli can’t always live with himself, he can certainly live with that.

What's Your Call? Leave a Comment:

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.