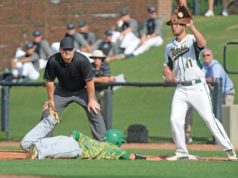

Umpiring a baseball game is full of visual challenges. Some are unusual and others are more common. In a recent game, the uninformed runner at third took his lead in fair territory. A hard-hit grounder down the foul line nearly hit the runner. The plate umpire focused on the possible hit runner and didn’t pay close attention to whether the ball passed over part of the bag. While every call an umpire makes involves a visual observation followed by the application of a rule, there are certain routine plays that present an exceptional visual challenge.

Touching bases.

It would be good for umpires if players were taught to put their foot in the middle of a base. While that does sometimes occur, coaches prefer a runner to graze the edge of the base with the side of his foot. That allows the runner to maintain his maximum speed while reducing the likelihood of turning an ankle. However, the preferred technique increases the difficulty the umpire has in determining if the base was actually touched.

Perhaps the most difficult base touch for an umpire to discern is that of a runner rounding third on his way to the plate. The plate umpire, at best, is going to be 45 feet away when the touch occurs. If the runner goes for the second-base side of the bag, the umpire has a reasonable chance to see contact with the base. However, if the runner puts his foot down in front of the base, there is no way the umpire can see between the base and the runner’s foot. In those cases, as well as others, the umpire should rule the base was touched if the foot was put down close enough to the base so that he “could” have touched it.

Base awards.

When a thrown ball goes over a fence or into the stands or other dead-ball area, runners, including the batter-runner, are awarded two bases. The base from which the award is made can be determined either from the time of the pitch or the time of the throw. In most cases, the award will be made from the time of the pitch. That is true if the throw is the first play by an infielder; however, there is an exception and that’s when the visual challenge to the umpire comes into play.

If all runners, including the batter-runner, have advanced at least one base at the time of the throw (when the ball is released by the fielder), the award is from the position of the runners at the time of the throw (NFHS 8-3-5; NCAA 8-3o3 Nt 1; pro 5.06b4G AR). And the umpires must know where the runners were when the ball was released.

Play 1:

B1 hits a grounder to F5 and the ball is muffed. His throw, which takes place (a) before, or (b) after B1 has crossed first base, is over F3’s head and into dead-ball territory. Ruling 1: F5’s throw was the first play by an infielder. In (a), B1 is awarded second — two bases from the time of the pitch. In (b), since B1 was past first base when the throw was made, he is awarded third base — two bases from the time of the throw.

It is worth noting “first play by an infielder” means what the fielder does after he fields the ball. The fielding of the ball is not the first “play“ even if he muffs or mishandles the batted ball, nor is it a play if he feints with either his arm or foot. A play or attempted play is a legitimate effort by a defensive player who has possession of the ball to actually retire a runner. This may include an actual attempt to tag a runner, a fielder running toward a base with the ball in an attempt to force or tag a runner, or throwing to another defensive player in an attempt to retire a runner.

Play 2:

With a runner on first, B1 grounds sharply to F4, who throws to F6 covering second, but not in time to get R1. F6 throws to first after B1 has crossed first base and the ball goes into the dugout. Ruling 2: F6’s throw was the second play by an infielder. R1 scores and because B1 was past first base when throw was made, he is awarded third base.

For all throws by outfielders and second or subsequent plays by infielders, the award is from the position of the runners at the time of the throw, so the umpires need to know the position of the runners in that situation as well. Adding to the challenge is the umpires won’t know the ball is destined to go out of play when the fielder releases it.

Play 3:

R1 is on first base and running on the pitch. B1 hits a line drive to F8, who makes the catch and fires the ball back to first ahead of R1’s return. The throw is wild and goes into the dugout. Ruling 3: That is a throw by an outfielder. R1 is awarded third, two bases from the last base he legally occupied at the time of the throw. The runner is required to retouch first even though the ball is dead.

Time plays.

Although a time play is not formally defined in any of the codes, it is generally understood to occur when the runner crosses the plate at approximately the same time as the third out is made at another base. The sequence of events determines whether the run scores. The umpires must know whether the out or the score occurred first.

Play 4:

With R2 on second and two out, B1 singles and is out at second trying to stretch the base hit. R2 scores. B1’s out occurs (a) before, or (b) after R2 scores. Ruling 4: In (a), the run does not score, but it does in (b).

The following is often misinterpreted to be a force play, but is of course a time play. A force play cannot occur after the batter-runner is retired.

Play 5:

With R1 on first, R3 on third and one out, B1 hits a line drive into the gap. R3 holds and R1 runs. The ball is caught. R3 tags and R1 attempts to return to first. The ball is returned to first (a) before, or (b) after R3 scores. Ruling 5: In (a), the run does not score, but it does in (b).

The preceding play can be an exceptional challenge for the plate umpire. After watching R3’s tag, he must read the quality and direction of the throw to properly position himself behind the plate (optimally on the extension of a baseline). He likely cannot get a glimpse of the play at first and must be guided by the base umpire’s vocalization of the out while remembering the out was made when F3 received the ball and not when the out was announced.

What's Your Call? Leave a Comment:

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.