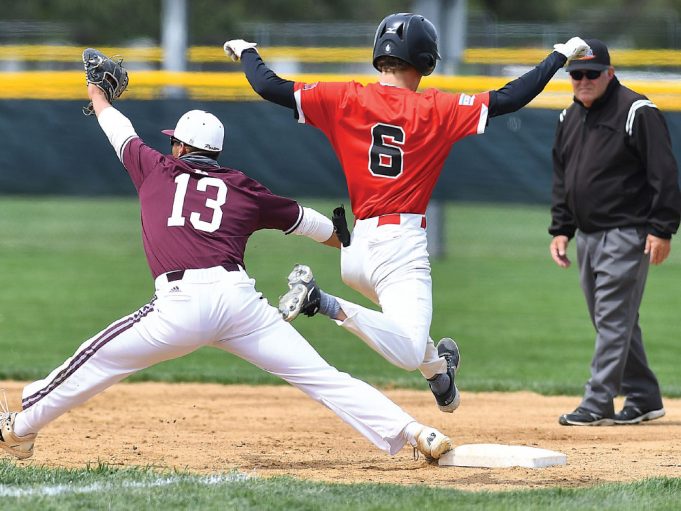

Last summer, I was working the bases as part of a two-person crew when it became apparent the defensive team was thinking about making an appeal involving a runner and a touch at second base. I had gleaned that much from overhearing the second baseman and shortstop chatting as a throw came back into the infield from one of the outfielders about how they thought the runner had missed the base.

The shortstop ended up with the baseball, jogged near the bag, touched it on his way by, then tossed the ball back to the pitcher. I did nothing, and the game proceeded accordingly.

Because I had heard their conversation and have a pretty good understanding of the game, I knew what the defensive team was trying to do. However, because I also have a good understanding of the rulebook, I also knew that given how the players handled this particular situation, there was nothing for me to do as an umpire. There are specific conditions that must be adhered to in order for a defensive team to make a valid appeal. Asking the umpire to engage in guesswork is not one of them.

Let’s begin by looking at the definition of the word “appeal” as found in the Merriam-Webster Dictionary: a serious request for help or support; an application (as to a recognized authority) for corroboration, vindication or a decision; an earnest plea; to make an earnest request.

The key words to take away from that definition are “request” and “application.” In other words, the party seeking redress must ask for it. There is no assumption allowed and it cannot happen accidentally.

So, back to the baseball field. All three rules codes (NFHS, NCAA and pro) spell out their procedures for proper appeals. In both the NFHS and NCAA, runners being out on appeal are covered in rule 8, which details all the rules related to baserunning. In pro, the applicable rule is 5.09.

There are two basic reasons for an appeal: a baserunner has either missed a base or has left a base before the ball is first touched on a caught fly ball. While the reasons for an appeal are fairly basic, the manner in which they must be initiated and how they may ultimately be administered are many. For the purposes of this article, we are not going to get too deep into the weeds about “why” an appeal is being made. Instead, our focus is going to be on the “how.”

The game I mentioned at the outset of this article was played according to NFHS rules. So let’s look at the following provisions in the penalty section of NFHS rule 8-2: A live-ball appeal may be made by a defensive player with the ball in his possession by tagging the runner or touching the base that was missed or left too early. A dead-ball appeal may be made by a coach or any defensive player with or without the ball by verbally stating the runner missed the base or left the base too early.

In order to make a valid appeal in the play described, the shortstop would have needed to make a valid live-ball appeal by either tagging the runner he believed missed second base (assuming the runner was standing on a succeeding base) and informing me why he was doing so, or by touching second base and informing me why he was doing so (or through an act unmistakable in both its intent as an appeal and the nature of the appeal). He needed to appeal to me the baserunner had committed one of those two baserunning infractions we already listed. Instead, he did neither. And, as such, I did nothing.

Because this was a summer league baseball game where the stakes were minimal, I opted to use the situation as a teachable moment — something I would never do in a regular-season varsity contest or college game to avoid the appearance of coaching players. When the shortstop came back onto the field the next inning to play defense, I instructed him his appeal was not valid, which is why I did not react. For all I knew, his stepping on second base while holding the baseball was nothing more than a happy accident, one for which I could not reward his team with an out had the baserunner erred in his baserunning responsibilities.

I also explained to him that had he executed a valid appeal, the runner would have been safe, as I clearly saw him touch the base. The last thing I wanted was the shortstop to later mischaracterize our conversation with his coach, believing the only reason he did not get an out was because of what one might try to term a “technicality.”

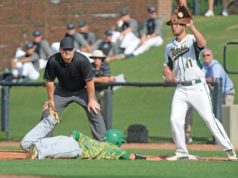

Let’s look at a recent example on a much bigger stage of why a team cannot be given credit for a happy accident. During Game 6 of the 2021 World Series, the Astros’ Michael Brantley and Braves pitcher Max Fried became briefly tangled up on a play at first base. Brantley, the batter-runner, was trying to beat out a ground ball and reached first base before Fried caught a throw and brushed the bag with his foot. However, Brantley never touched first base. The ruling umpire, Doug Eddings, signaled Brantley was safe on the play.

Replays showed Fried was the only one of the two who actually touched first base. However, according to baseball rules not just at the MLB level, but also the NCAA and NFHS levels, once a batter-runner advances past first base, if he does so before a defensive player touches the base, he is ruled safe, and the only remedy for the defense is a valid appeal (NFHS 8-2 Pen.; NCAA 8-6a3; pro 5.09c2).

Had Fried touched first base and announced his intention he was appealing the fact Brantley missed the base, an out should have been ruled. Had Fried tagged Brantley before the latter safely returned to first base, an out should have been ruled.

The fact that Fried’s foot brushed the bag moments after Brantley passed it? A happy accident that has no bearing on the play.

What's Your Call? Leave a Comment:

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.