A lime green toy pig, gifted to Pati Rolf by the distraught motorist who accidentally struck her on snowy Minnetonka Boulevard in Hopkins, Minn., nearly 50 years ago, endures all these years later somewhere in the attic of her home in Pewaukee, Wis. There is a reason why that cuddly little toy she used to clutch didn’t quietly fade away with so many of her other childhood possessions. One of the most celebrated volleyball officials in the world would gradually come to realize the significance of what that toy pig she received around November 1972 represents in her life, and it sure packs a hell of a wallop now. What it symbolizes is the true meaning of selflessness and passion, inspired by a motorist who was blameless in an accident that easily could have killed her, yet was so overwhelmed by grief that he kept bringing her gifts daily. He only stopped when Pati’s mother, Kathy, gently encouraged him that he had done more than enough. “Why is that pig so particularly important?” Rolf asked. “That pig is just the generosity of him. I just kept that pig because of the generosity of that man.” That seed of compassion would grow within Rolf over the next half century, motivating her to try to make a difference in any way she could, whether it was spreading herself thin as a wife and mother while on the Duluth (Minn.) School Board, volunteering as a foster parent, reading to children in public schools or coaching a girls’ inner city volleyball team when its coaches were on break. Those characteristics have continued to serve her so well as director of officials development with USA Volleyball, the latest stop in what has been such a long, winding and often grueling career road. Every official has a friend in Rolf, who mixes positive reinforcement with plenty of hard-earned wisdom after earning historic assignments at the highest levels of college and in the Olympics.

“There aren’t very many people who have filled as many different roles as she has and found at least a level of success at each one of them,” said Marcia Alterman, a longtime referee who is an assigner for several conferences, including the Big Ten. “We talk all the time about finding young women who want to go into officiating and she’s the role model for what we can point to and say, ‘Look where you can go if you can really, really find the passion. That’s the end point. That’s what you can end up being.’ So she’s provided that goal for a lot of people — and not just women.”

Maybe there’s another reason why that toy pig has withstood the test of time. It could be submitted that it symbolizes survival for a woman who has survived so much, starting with that near tragedy on Minnetonka Boulevard in 1972. She would go on to endure a devastating and controversial dismissal as coach of the Marquette University women’s volleyball team in November 2008 — “that almost killed me,” she insists — her termination in the same role at East Carolina three years later, the death of her 2-month-old niece, Sophie, in 2001, and the suicide of her sister, Teri, in 2015. There was prolonged healing involved with each of those incidents, yet she has re-invented herself into someone extraordinary.

It’s difficult to imagine anyone with more gusto than Rolf, who enthusiastically answered each question for this story with an insightful explosion of words that created multiple layers of thought. One of the most influential movers and shakers in volleyball officiating is so full of life after emotionally being left for dead several times in her life. And, quite possibly, the best is yet to come as she closes in on her 57th birthday.

Nothing could get Rolf out of bed during the endless winter of 2008-09, after she was fired by Marquette. These days, nothing can stop her. And so much seems to be traced back to that lime green pig in her Pewaukee attic.

“That green pig will be with me until my very last day,” Rolf said.

Yes, it represents that much.

“It’s just the way she continues to forge ahead,” said Katy Meyer, executive director of the Professional Association of Volleyball Officials. “A door closes, another one opens. She’s not going to be taken down by life’s situations. I’ve definitely seen that in her in all the years I’ve known her.”

Alterman has noticed that same staying power within Rolf.

“She has a huge level of perseverance,” Alterman said. “Part of that comes because she tends to be one of the most positive people I know. She can look at the bright side of almost anything. I’ve seen her go through an awful lot. I spent some time with her when she was dealing with issues with her older sister (Teri) and it was hard. But she manages to turn it around. She’s very spiritual and she relies a lot on that when the times get tough.”

A 9-year-old, pony-tailed tomboy at the time, Rolf was returning home with sister Paula from ice skating at Burns Park in Hopkins, Minn., that day in November 1972. Their mother, who used to allow almost unlimited and unsupervised access to the Minnesota outdoors for her five daughters, also used to enforce a strict curfew. And the Rolf sisters — Teri, Kristi, Viki, Paula and Pati (a brother, Kurt, would become the last sibling) — used to push that curfew to the limit. On that fateful day, when there was an urgency to get home, Paula scurried across the road and then yelled back at her little sister, “You chicken! Come on! We’ve got to go!” Without looking, Pati darted into the road and was hit so hard by an oncoming car that she went airborne over the windshield for about 30 feet before plopping into a snowdrift. The next sound she heard was the screaming siren of an ambulance rushing her to a hospital and a lengthy recuperation was in store. The miracle is that little Pati was even able to hold the pig that motorist would one day bring her during those first few weeks.

“She was covered in bruises from head to toe, but it’s crazy — she never broke anything inside,” Viki Rolf said. “It was shocking, really. The hospital medical community couldn’t believe it.”

The girl who somehow cheated death would make the most of her childhood, from fearlessly climbing tall trees to pitching against boys for the local Little League baseball team. That’s right — the best pitcher on her team had a waistlong ponytail extending out of the back of her baseball cap. Her late father, Keith, who elevated his poor family into a more comfortable life by building one of the largest gun merchandise stores in Minnesota, was an avid outdoorsman who used to fly with Pati to remote fishing locations. “I just loved that,” she recalls. Viki Rolf recalls frequent adventures with her sisters that sometimes teetered toward downright hazardous activities. “Us kids had extreme independence when we were on trips — super risky,” Viki said.

“We would go on lakes after fly fishing and we would be in this incredible wilderness finding a waterfall up a tiny river, where literally no one would have ever found us, ever. We would go on the lake and hope the motor wouldn’t break down and would somehow luckily always make it back.”

Rolf continued to tempt fate as she grew older, once diving into the ocean from a moving cruise ship after realizing she had forgotten something during a family vacation in Puerto Vallarta in 1985 (more on that later). And there were the times she used to push her cherry-red, Suzuki motorcycle up to 100 miles per hour until another road accident in 1987 gave her a life-changing epiphany. As for the sport that would eventually define her, Rolf didn’t pursue volleyball until she was at North Junior High School in 1976. She had the rawest of skills at the time. What’s more, she initially didn’t have the guidance to progress.

“When I showed up for volleyball, we didn’t have a coach,” she said. “This husband and wife who were volunteers at the school volunteered to coach and they were absolutely not coaches. They knew absolutely nothing about volleyball, but we wouldn’t have a team without them.”

By a quirk of fate, her first coach at Hopkins Eisenhower High School as a sophomore in 1978 was Glen Lietzke, who would become a national figure in the sport. Career accolades for the 2018 inductee into the American Volleyball Coaches Association Hall of Fame include creating the Austin (Texas) Juniors Volleyball Club that he would lead to two USA Junior National championships and serving as an assistant for the University of Texas women’s volleyball team, which he helped to seven national championships. It was Lietzke who first nurtured Rolf in volleyball.

“How did it happen that one of the best coaches in the country ended up being my 10th-grade coach in his first coaching job?” Rolf said. “It’s just ridiculous when you think about it. He made you think that you could do anything. Even when I wasn’t very good, he was so demanding and he just made me believe that no matter how bad I was, if I worked hard enough and had his energy and passion, miracles could happen. A big one he taught me was to never give up on my teammates. If a teammate hits something that goes in the wrong direction, go running after it and save it for your teammate. You’ll make them feel better and then you’ll feel better. That was a big theme of his.”

Leitzke, who coached Rolf only as a sophomore before becoming a college head coach at Wisconsin-River Falls, recalls a memorable first encounter with the future standout.

“This opened my eyes to how good of an athlete she was,” Leitzke said. “The first day of practice, she’s not there. I was told Pati Rolf was going to show up and I was going, ‘OK, where’s Pati because she’s not here today?’ Somebody told me she was playing in a baseball tournament. I said, ‘Oh, you mean a softball tournament?’ And I was told, ‘No, a baseball tournament.’ So she came rolling in after the baseball tournament and she was one of the best athletes I ever coached. She was a sophomore playing with seniors and she was not only holding her own skill-wise, but responsibility-wise and everything else.”

By Rolf’s senior year, she was a 5-foot-8 middle hitter who had developed into a star. She actually received a scholarship for basketball from North Dakota State and doubled in both sports before concentrating solely on volleyball as a junior and senior.

She was a four-year starter in volleyball who was named most valuable player in the North Central Conference as a senior and she was someone who desperately wanted to win. Amy Raymond discovered that early in their career together.

“When we came into our first preseason, we could not stand each other!” said Raymond, who would go on to become Rolf’s maid of honor (Pati would be the same for her). “I thought she was kind of weird, arrogant and standoffish and I was kind of loud and boisterous. By the second tournament, all of a sudden, I was like, ‘OK, this girl wants to win and is serious about volleyball like I am.’ When we got to room together, we were like, ‘Yes!’ and we’ve been best friends ever since. Emotional bulls— gets in the way of so many women’s athletics and we didn’t have that.”

Raymond recalls a time at practice during their senior year that involved an expletive-laced encounter between the two. “The drill was over, we both said ‘sorry’ and it was over,” she said.

Perhaps Rolf’s first real emotional crisis occurred after her senior season in the fall of 1984. Just 21 at the time, her competitive desires were no longer being fulfilled and there was an enormous void. The choices she made for excitement following her playing career were hazardous, to say the least. Like riding her motorcycle up to 100 miles an hour through the dark, quiet streets of Fargo, N.D., night after night. And there was that time she dove off a large cruise ship during that family vacation at Puerto Vallarta in 1985 and tried to swim toward shore.

“This is where my mother really thought I had gone nuts,” Rolf said. “I was really because sports was done. I had accidentally left something behind and this cruise ship was leaving the harbor and was out in the open water and I said, ‘Oh, I forgot my backpack!’ Kristi said, ‘Oh, whatever,’ and I said, ‘No! I’m going to get my backpack!’ If someone says you can’t do something, if you’re from Minnesota, that means you can. So I went and leapt off of the ship. It was probably four stories. I leapt into the ocean and swam back to shore, which was a long way! And the horns on the ship went off because the guys on the ship didn’t know. They thought I was trying to kill myself. I got picked up in a catamaran because I realized I had kind of overestimated myself.”

One year later, Rolf and her future husband, Kent Larson, were staying at her parents’ home and sleeping in separate rooms to satisfy her strict mother. One night during the summer of 1986, they sneaked off into the attic for a late-night rendezvous and became the parents of a son, Graydon, in March 1987 (they would welcome daughter Madison seven years later). Kent and Pati were married in August 1987, but only after she had sown her last wild oats. This time, the setting was Highway 7 in Hopkins and Rolf was tempting fate on that Suzuki once again wearing only a T-shirt, shorts and a pair of flip-flops.

“I was in Minnesota, I was doing a camp and a woman slammed on her brakes,” Rolf said. “Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to stop the bike and had to lay it down on the highway just past our house. It was very painful, to say the least. I just lost a lot of skin. Then my mother had to come and get my bike with my father, put me in the car and bring me off to the doctor. And then she literally looked at me and she goes, ‘Honey, it’s time to grow up now. You’ve got a baby.’”

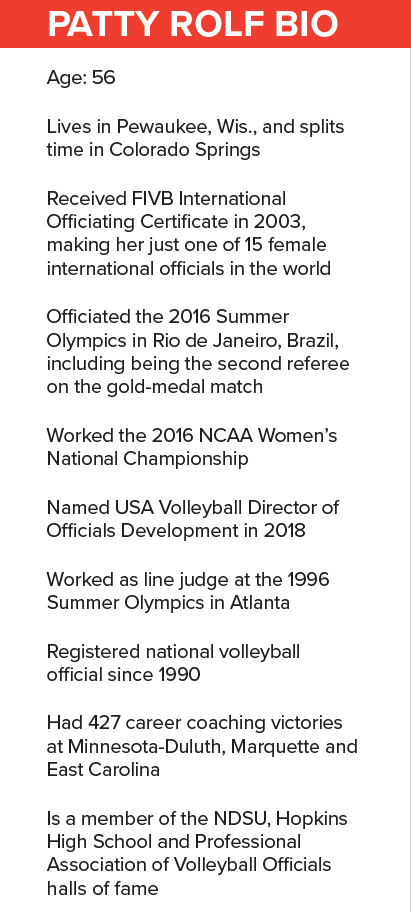

Volleyball had remained Rolf’s first love and she developed a Juniors program during that time in Duluth. She became the head coach at the University of Minnesota- Duluth at the age of 25 in 1988 and went on to coach the Bulldogs to a 310-169 record and 11 Northern Sun Intercollegiate Conference (NSIC) championships. Five times she was the NSIC Coach of the Year, and then it was off to Division I Marquette, where she had mixed success.

She led the Golden Eagles to three straight winning seasons (2004- 06) for the first time in program history and the Conference USA Tournament finals in 2004. And then one day in November 2008, with four games still remained during what was a disappointing season, she was summoned into the office of Steve Cottingham, Marquette’s athletic director at the time.

“You don’t get fired during the middle of a season, ever, unless you do something terrible,” Rolf said. “It was right after the signing season and he called me into his office and said, ‘Hey, we want to go in a different direction.’ I literally didn’t leave my house for six months. I was so devastated because I couldn’t get a job. I had a great record and every place I applied to asked, ‘Why did your AD fire you in the middle of the season?’ and I couldn’t answer the question. I just said, ‘I don’t know.’ So they thought something bad happened.”

When asked for a possible reason, Rolf conceded she was somewhat outspoken. That same question was put to Ann Pufahl, NCAA secretary-rules editor and the director of intramural sports at Marquette, who is close friends with Rolf.

“I know that her and the women’s basketball coach at the time (Terri Mitchell) did not get along and the women’s basketball coach carried more clout, so I think that was a piece of it,” said Pufahl, who still works at Marquette and feels Rolf’s termination at that point in the season was unfair.

A devastated Rolf used to aimlessly walk around Pewaukee Lake in the aftermath of that dismissal, not realizing that her concerned husband was trailing her in the shadows. Former Marquette athletic director and men’s basketball coach Hank Raymonds eventually intervened and helped Rolf get hired as East Carolina’s coach, where she served from 2009-12. But after not being able to turn around the program, she was dismissed by athletic director Terry Holland. And more hard times were in store. Rolf would become a self-described professional referee working 500 games a year.

“She went to being a volleyball ref, but you can’t really make a living at that without killing yourself,” said Pufahl. “I was so worried about her when she was doing that because I assigned for the Big 12 Conference and I was using her. And then I found out she would drive to Kansas — the conference would pay for an airplane ticket — just to get the mileage money. And she would sleep in her car. When I heard that, I stopped sending her to drivable places just because I didn’t want her sleeping in parking lots at night. When the USA Volleyball job opened (in 2018) and she was selected, it just turned her around. It was like, ‘I have a purpose.’ She had a meaning, she had authority and she had people asking her questions.”

There were still hard times ahead. Rolf’s eldest sister, Teri, committed suicide in March 2015 after being burdened by a number of medical ailments. “I felt like I had failed her, in a sense,” Rolf said. Pati’s life had already been rocked 14 years earlier when her 2-monthold niece, Sophie, died of an undiagnosed medical issue. But Rolf is a fighter and she has been at her best after experiencing so much. The numerous achievements for Rolf, a certified FIVB official since 2003, include working the 2016 Rio Olympic Games, where she became only the second woman to referee the women’s gold-medal match. Two years later, she became the first woman selected to work a men’s NCAA national championship match as the first referee.

That same year, she became USA director of officials development, a job she relishes. One of her pet projects is attracting younger officials to the sport.

“In the next 10 to 20 years, we will have a significant number of our refs retiring,” she said. “And I mean like 60 to 70 percent, with no backfill on that. So last year (2018), we started what we call the High Performance Officials Program where we’ve identified emerging referees and we’re making it a priority for them to go to High Performance to get special training from Olympic referees. We’re bringing in Olympic referees from across the world.”

And Rolf stands among the very best.

“She’s trying to be a mentor with all these young up-and-coming officials,” Pufahl said. “She’s there for them and talking to them. She’s just a great human being. I don’t know a better way to describe it. She’s always willing to listen, always has advice, is always willing to give you a different perspective to think about, which is what I probably like most about her. She looks at angles most people don’t.”

But then, Pati’s eyes have seen so much.

Peter Jackel is an award-winning sportswriter from Racine, Wis.

What's Your Call? Leave a Comment:

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.