The softball strike zone has not changed for a long time; it is still the zone explicitly described in the rules for each softball code. There are slight differences in the rule among the codes so let’s start with these definitions from each of the codes:

NFHS and USSSA Softball — forward armpit to the top of the knees, any part of ball.

USA Softball — the armpit to the top of the knees; any part of ball.

NCAA — bottom of the sternum to the top of the knees, top of the ball.

Area Above Home Plate

Area Above Home Plate

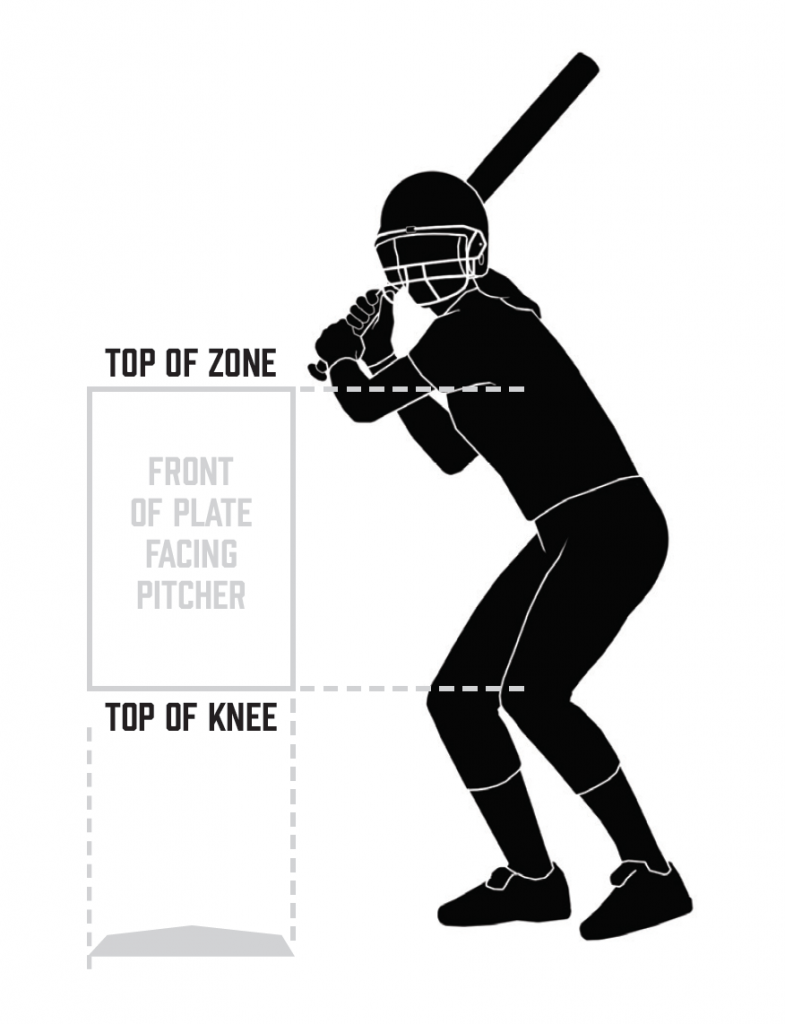

To get a better perspective of an actual strike zone, it is helpful to visualize it as a hexahedron (also called a cuboid) above the entire plate. Visualize this threedimensional zone above the plate with the top at the armpit (NCAA — bottom of sternum), the bottom at the top of the knees, and two of its sides directly above the outer edges of the plate.

Judge the pitch as it crosses the entire plate, not just the front of the plate. Pitchers who throw good drop and rise balls should be given this entire zone.

Horizontal Zone

The horizontal aspect of the strike zone includes the 17 inches of the plate plus the outer edge of the ball. The diameter of the ball is 3.82 inches. By including this extension for both sides of the plate, the actual (and “callable”) strike zone is 24.64 inches wide. If the circumference of the ball barely grazes the plate, it is a strike if it also satisfies the vertical zone. This horizontal aspect is fixed and is the same for every batter.

Vertical Zone

The vertical aspect of the strike zone is determined by the armpit (or bottom of sternum for NCAA) and the top of the knee as the pitch crosses the plate. This vertical aspect is variable, dependent upon the distance from the batter’s upper limit and her knees. It changes from batter to batter; it is unusual for batters to have the same exact height and natural batting stance. It is more likely that an umpire will have as many as 18 different strike zones during a game (for starting players), and probably more as substitutes are entered.

All batters do not have a stance with both knees at the same height. We are now seeing more batters with a stance in which one knee is lower than the other knee when they establish their natural batting stance in the batter’s box.

Umpires need to recognize this and be aware that the guideline to use is the top of the knee closer to the ground as the bottom parameter for the zone.

Home Plate as It Applies to the Strike Zone

How often have you heard, “That ball hit the corner” or “Hey, Blue, that plate has corners”? Yes, it does have corners. There are actually five corners on the plate. People are typically referring to the front corners in the above quotes, but none of the five corners determine a strike. For a pitch to be a strike for its horizontal aspect, it must touch a side of the plate which is parallel to the batter’s box line.

Tips for Calling the Strike Zone

We must work for an accurate strike zone throughout the game. In the past, there has been an emphasis on being consistent as well as accurate. We should no longer be talking about consistency because if accuracy is our top priority, our zone will be consistent.

With that in mind, an aggressive strike zone is better than a tight strike zone. This does not mean you call strikes that are not strikes.

What is the difference? An aggressive strike zone means the umpire does not miss the strikes at the outer edges of the zone.

A tight zone indicates the umpire is missing those strikes.

Use Your Tools

The first step is to realize that, as plate umpires, we have a valuable tool in our kit — our brush. Let your catchers and batters know from the start — by communicating nonverbally with that tool — you are very aware of the outer edges of the plate and will call them.

After the defense has finished its warmup pitches in its half of the first inning, wait until both the batter and catcher are in the area of the plate. Make a bit of a production by sweeping off the outside edges on both sides of the plate as well as the plate itself. Continue to do this at the beginning of each half-inning, so the batters and catchers have constant reminders that the corners are strikes (within the vertical zone).

If there is black around the outside edges of the plate, it is not included in that 17 inches of the horizontal zone. But we know if the pitch grazes the outside edges, a strike call is a good call. And we also know that catchers will frequently tell their teammates what kind of zone “Blue” is calling. We do not have to be rocket scientists to realize that the more hitters swing, the fewer pitches must be called. One big caveat — follow through with this by ringing up strikes on the outside edges or all this effort is wasted.

Taking the Vertical Aspect to Another Dimension (3D)

Warning, there will be math. As far as the vertical dimensions of the strike zone, here are some statistics for college softball athletes, taken from multiple studies (use these as a reference; obviously, they would be different depending on the age level of the game):

- One of the smallest players who played college softball was 4’11”

- The tallest players do not get much taller than 6’2”

- The average height of a college softball player is between 5’6” and 5’7”

- The average distance from the bottom of the sternum to the top of the knees for a 5’7” female is about 22”

Putting all these factors together, it could be said that the strike zone for an average college softball player is an area that is 24.64 inches wide, 17 inches in depth and has a vertical length of 22 inches. This equates to just over 5.3 cubic feet for the strike zone for an average college player. Different batters’ heights result in different vertical aspects for each batter and taking the smallest and tallest players, the strike zone could range from 4.75 cubic feet (player height 4’11”) to 5.95 cubic feet (player height 6’2”).

Obviously, we are not thinking about the cubic area of the zone as we get into our set. The important factor is that you visualize that cubic area as you get set for the pitch. Then, stay with the pitch for the entire area over the plate.

John Bennett, Anaheim, Calif., works NCAA, high school and travel softball, and is involved with training umpires at all levels. He worked the 2014 NCAA Division II championships and multiple other championship series.

What's Your Call? Leave a Comment:

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.