By Leon Davis

No, the Pac-10 title was not on the line, but when Stanford’s Cardinal traveled to Berkeley to take on California’s Bears it was an important football game. Nov. 20, 1982, would be John Elway’s last regular-season game for Stanford, and he was in the running for college football’s prestigious Heisman Trophy. Plus, Stanford was “on the bubble,” hoping for a bowl bid.

The conference rivalry lived up to tradition. Recalls Charles Moffett, the game’s referee: “Even without those last four seconds it was a great game. There were incredible runs and magnificent catches by both teams. Elway passed for 333 yards and treated the fans to one of his patented, last-minute, come-from-behind drives capped by a 35-yard field goal. With four seconds left, Stanford led Cal, 20-19.

Those last four seconds produced college football history as one wild, improbable play would forever identify the entire contest as “the band game.”

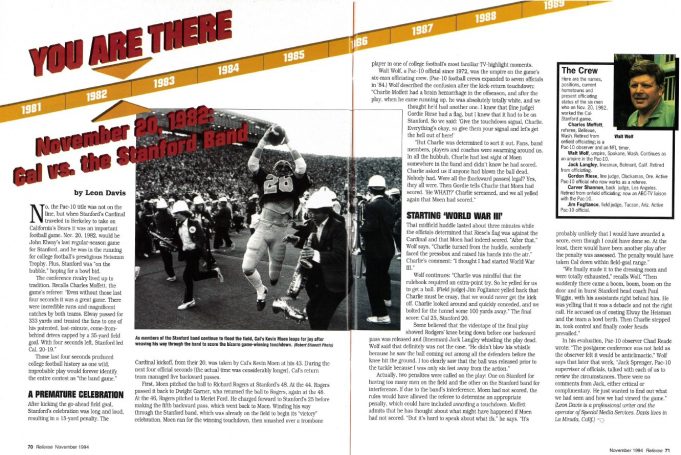

After kicking the go-ahead field goal, Stanford’s celebration was long and loud, resulting in a 15-yard penalty. The Cardinal kickoff, from their 20, was taken by Cal’s Kevin Moen at his 43. During the next four official seconds (the actual time was considerably longer), Cal’s return team managed five backward passes.

First, Moen pitched the ball to Richard Rogers at Stanford’s 48. At the 44, Rogers passed it back to Dwight Garner, who returned the ball to Rogers, again at the 48. At the 46, Rogers pitched to Meriet Ford. He charged forward to Stanford’s 25 before making the fifth backward pass, which went back to Moen. Winding his way through the Stanford band, which was already on the field to begin its “victory” celebration. Moen ran for the winning touchdown, then smashed over a trombone player in one of college football’s most familiar TV-highlight moments.

Walt Wolf, a Pac-10 official since 1972 was the umpire on the game’s six-man officiating crew. (Pac-10 football crews expanded to seven officials in ’84.) Wolf Described the confusion after the kick-return touchdown: Charlie Moffett had a brain hemorrhage in the offseason, and after the play, when he came running up, he was absolutely totally white, and we thought he’d had another one. I knew that (line judge) Gordie Riese had a flag, but I knew that it had to be on Stanford. So we said: “Give the touchdown signal, Charlie. Everything’s okay, so give them your signal and let’s get the hell out of here!”

“But Charlie was determined to sort it out. Fans, band members, players and coaches were swarming around us. In all the hubbub, Charlie had lost sight of Moen somewhere in the band and didn’t know he had scored. Charlie asked us if anyone had blown the ball dead. Nobody had. Were all the (backward passes) legal? Yes, they all were. Then Gordie tells Charlie that Moen had scored. ‘He WHAT!?” Charlie screamed, and we all yelled again that Moen had scored.”

That midfield huddle lasted about three minutes while the officials determined that Riese’s flag was against the Cardinal and that Moen had indeed scored. “After that,” Wolf says, “Charlie turned from the huddle, somberly faced the pressbox and raised his hands into the air.” Charlie’s comment: “I thought I had started World War III.”

Wolf continues; “Charlie was mindful that the rulebook required an extra-point try. So he yelled for us to get a ball. (Field Judge) Jim Fogltance yelled back that Charlie must be crazy, that we would never get the kick off. Charlie looked around and quickly conceded, and we bolted for the tunnel some 100 yards away.” The final score: Cal 25, Stanford 20.

Some believed that the videotape of the final play showed Rodgers’ knee being down before one backward pass was released and (linesman) Jack Langley whistling the play dead. Wolf said that definitely was not the case. “He didn’t blow his whistle because he saw the ball coming out among all the defenders before the knee hit the ground. I too clearly saw that the ball was released prior to the tackle because I was only six feet away from the action.”

Actually, two penalties were called on the play: One on Stanford for having too many men on the field and other on the Stanford band for interference. If due to the band’s interference, Moen had not scored, the rules would have allowed the referee to determine an appropriate penalty, which could have included awarding a touchdown. Moffett admits that he has thought about what might have happened if Moen had not scored. “But it’s hard to speak about what ifs,” he says. “It’s probably unlikely that I would have awarded a score, even thought I could have done so. At the least, there would have been another play after the penalty was assessed. The penalty would have taken Cal down within field-goal range.”

“We finally made it to the dressing room and were totally exhausted,” recalls Wolf. “Then suddenly there came a boom, boom, boom on the door and in burst Stanford head coach Paul Wiggin, with his assistants right behind him. He was yelling that it was a debacle and not the right call. He accused us of costing Elway the Heisman and the team a bowl berth. Then Charlie stepped in, took control and finally cooler heads prevailed.”

In his evaluation, Pac-10 observer Chad Reade wrote: “The postgame conference was not held as the observer felt it would be anticlimatic.” Wolf says that later that week, “Jack Sprenger, Pac-10 supervisor of officials, talked with each of us to review the circumstances. There were no comments from Jack, either critical or complimentary. He just wanted to find out what we had seen and how we had viewed the game.”

Note: This article is archival in nature. Rules, interpretations, mechanics, philosophies and other information may or may not be correct for the current year.

This article is the copyright of ©Referee Enterprises, Inc., and may not be republished in whole or in part online, in print or in any capacity without expressed written permission from Referee. The article is made available for educational use by individuals.